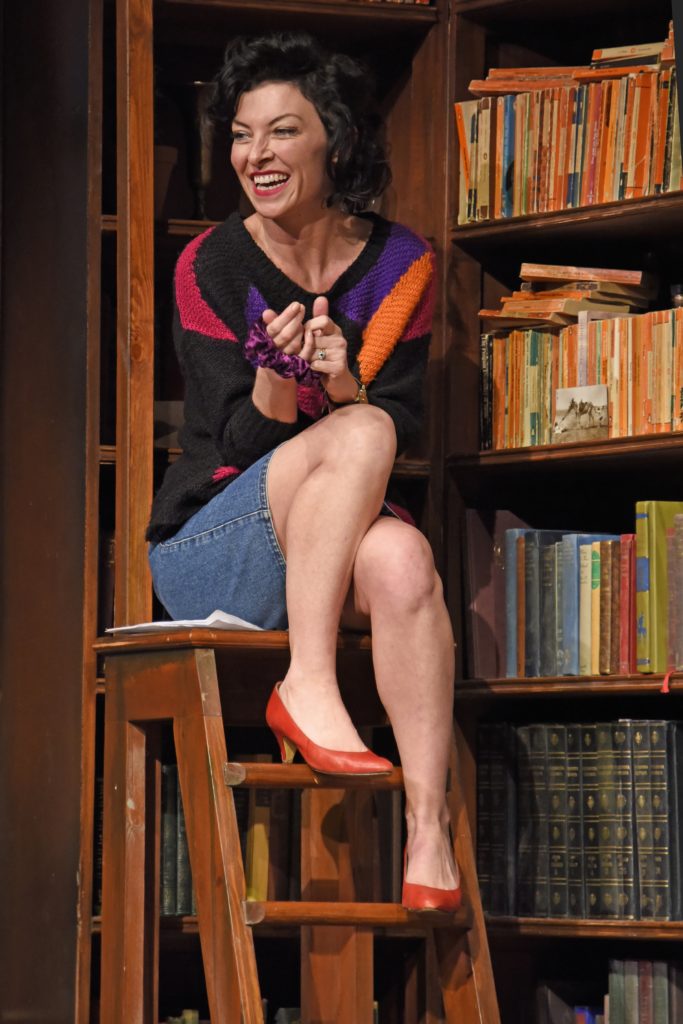

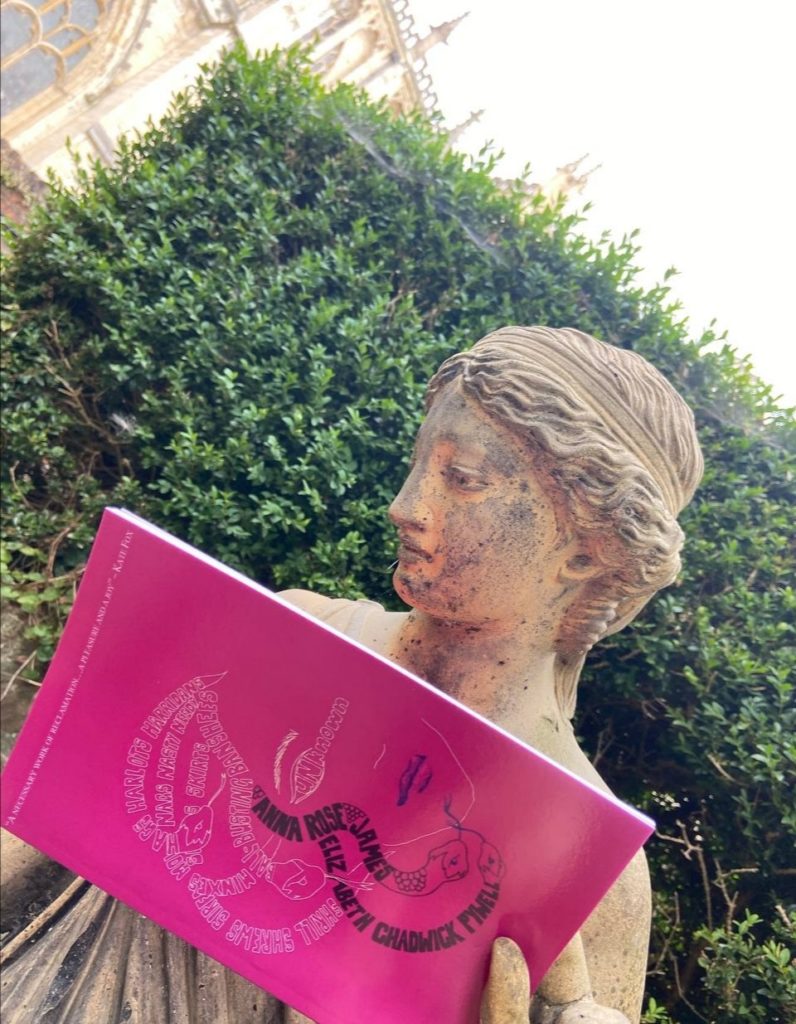

YORK poets, teachers and actor-directors Anna Rose James and Elizabeth Chadwick Pywell launch Unknown, a joint collection inspired by forgotten women from myth and history, online tonight (26/8/2021) at 7.30pm.

To “attend” the livestreaming, head to: eventbrite.co.uk/e/unknown-the-book-launch-tickets-166073970717?aff=eand

“Our publishers, Stairwell Books, have booked an online launch for us, as the in-person venue options weren’t entirely Covid-comfortable, so we’re potentially putting that off now until next year,” says Anna, a queer, bisexual writer, performer, translator and theatre critic of mixed British and Asian heritage, who writes flash fiction, auto-fiction, memoir and scripts for stage and screen, as well as poetry.

“I’ve been pretty much hibernating since March last year, but I co-wrote this collection with Liz last summer and it’s something we’ve created that we’re very proud of.”

Among those impressed already by Anna and Liz’s 27 poems on “women whose names should be on your lips” is Yorkshire poet and comedian Kate Fox, whose endorsement on the back cover reads: “Unknown introduces and re-introduces us to women who might otherwise slip through history and culture’s ever-widening female-shaped holes.

“These are brisk and beautiful poems. Works of reclamation like this are ongoingly necessary – which is frustrating – but when they’re done so well, they are a pleasure and a joy.”

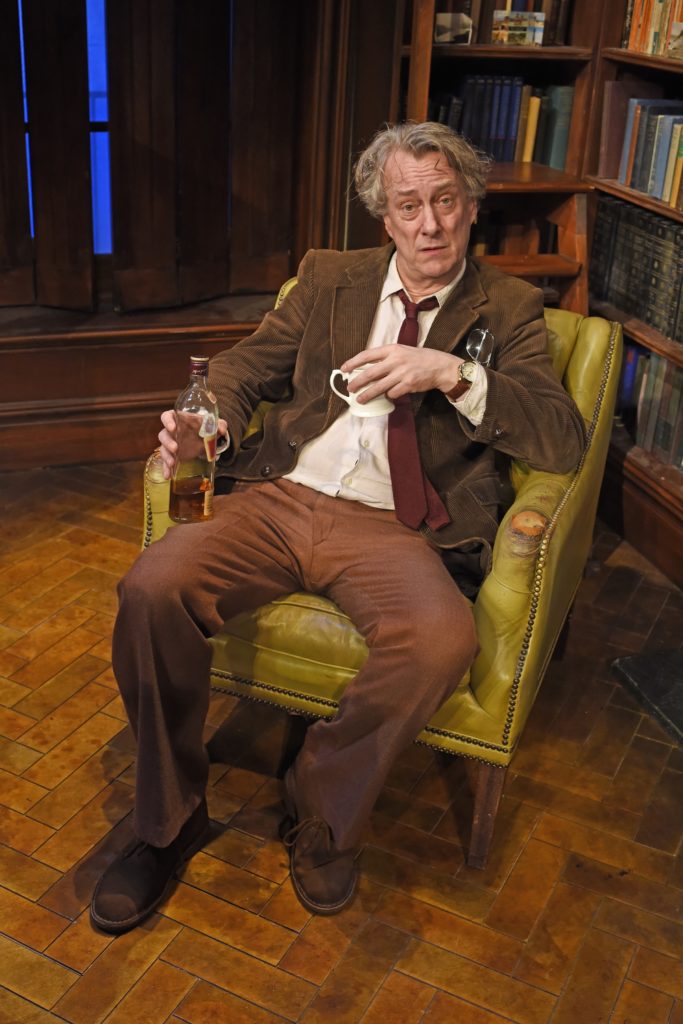

Professor Emeritus Graham Mort enthuses: “Linguistically charged, rhythmically and technically assured, theatrically daring, this collection restores mythical and historical female figures to the human imagination.

“The poems are robust, playful, tender and compassionate and the work as a whole forms an unsentimental and richly detailed testament to women’s resistance.”

Unknown is a coming-together between two York women over a “shared love of women, inspired by those from history and legend who have touched our lives, or the world, and left us changed”.

“We first met at the Queer Book Club in York,” says Liz, a Welsh-born poet and writer of short stories and flash fiction, who provides private tuition in English, drama, and creative writing, runs creative writing groups for children and performs occasionally at open-mic nights in York during non-lockdown times.

“When I had Covid, Anna put some of her zines through my door, which was lovely as I was very bored and very ill, and though I’d always written, I’d never published my work, but that was the starting point for Unknown.”

Anna recalls: “I was furloughed from work at Macmillan Cancer Support and was palming off these zines on people who couldn’t escape from their homes! I got a call from Liz within ten minutes.”

They settled quickly on a theme for their collaboration. “Just women to begin with, but then it became women who are under-represented in myth and history,” says Liz.

“We set ourselves the challenge of researching these women and then writing about poems about them.”

Anna, co-founder of Sonnet Sisters, Six Lips Theatre and The Podvangelist, says: “Some of the women are a lot more unknown than others, so that’s why the research expanded into taking in both misrepresented and under-represented women…

… “And we also considered how these stories might have been told if they’d not been told by men,” says Liz. “These are her-stories, not his-story.”

Helpfully, the collection includes an index of the subjects to facilitate readers reading more about the featured women, among them Medusa; Persephone; Ceridwen the witch; pirate captain Ching Shih; Gentleman Jack (Anne Lister); revolutionary pilots Bessie Colman and Major Marina Raskova; tennis champion Althea Gibson and characters from Norwegian folklore, Shakespeare and Tarot.

“We bashed out the first body of poems really early on, each writing a poem in a day, for an immediate response and then editing them later,” says Anna “Getting an instant reaction was lovely as normally writing poetry is solitary.”

Anna was drawn more to history, Liz more to myth. “I would always call myself a dreamer, but I think Liz pulls out all the vagaries of myths, whereas I respond to pulling out all the details of historical figures,” says Anna. “Liz responds to the lack of detail or basic plot lines when she engages with myths.”

Liz observes: “I think we write in really different ways but that works really well together, and the project has been really collaborative. It’s been great to have someone to bounce ideas off, whereas often I write with total autonomy.”

Happy to be a “figure of mystery” when performing at open-mic nights, Liz has a pamphlet on its way called Breaking (Out), published by Selcouth Station. “It’s about coming out as a lesbian when you’re married to a man, which is not a typical life journey but had to be done,” she says.

Meanwhile, tonight she and Anna will read poems at the 7.30pm livestreamed launch, as will fellow writers Hannah Davies and Kali Richmond.

Who are Stairwell Books?

This York small press, based in Lowther Street, publishes the works of Yorkshire poets and writers, plus the international literary and arts journal, Dream Catcher.

Unknown can be bought at stairwellbooks.co.uk for £8 plus postage and packing.

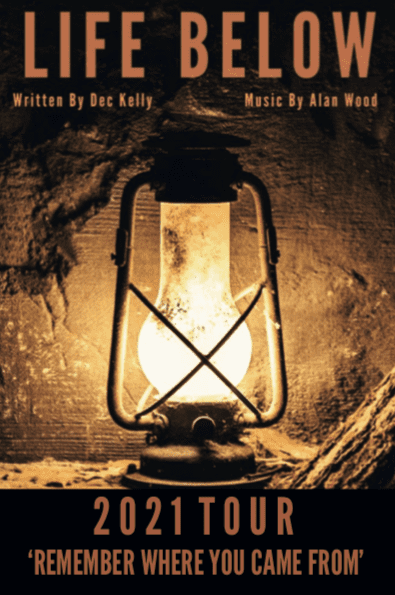

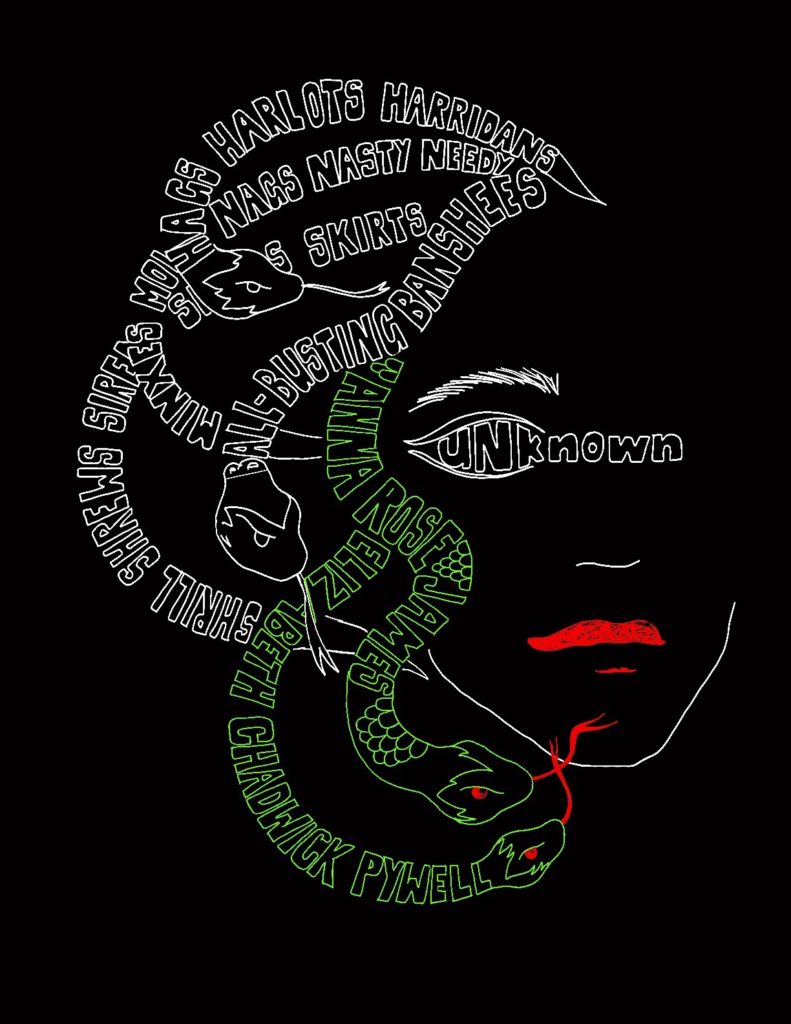

CharlesHutchPress loves this “acid” alternative cover and ponders whether Stairwell Books would consider doing a print run, should Anna and Liz plan to do any readings at summer festivals.

“That’s absolutely something Liz and I had floated with Stairwell too,” says Anna. “We love the idea of limited-edition variants; we actually found it a bit difficult to choose our favourite from the options artist Lisa Findlay Shaw sent through.”

You are very welcome to send your support for such a variant to founder Rose Drew at rose@stairwellbooks.com.

Lisa Findlay Shaw can be found on Instagram at @thiscronecreates.