FROM giant dinosaurs to a heavyweight comedian, hardcore songs to a royal reading, Charles Hutchinson seeks to make life eventful.

Dinosaurs make a comeback: Jurassic Earth, Grand Opera House, York, January 28, 1pm and 4pm

JURASSIC Earth’s “live dinosaur show” roams York in an immersive, interactive, 75-minute, storytelling experience for all ages with state-of-the-art, animatronic, life-like creatures.

Audiences are invited to “bring your biggest roar and your fastest feet as you take Ranger Danger’s masterclass to become an Official Dinosaur Ranger – gaining the skills you need to come face-to-face with the world’s largest walking T Rex, a big-hearted Brontosaurus, tricky Triceratops, uncontrollable Carnotaurus, vicious Velociraptors and sneaky Spinosaurus”. Box office: atgtickets.com/york.

Holocaust memorial concert of the week: York Chamber Music Festival, Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet For The End Of Time, York Minster, Tuesday, 7pm

YORK Chamber Music Festival marks Holocaust Memorial Week – and the start of the festival’s tenth anniversary – with a performance of “one of the greatest pieces of music from the 20th century”, written and premiered in the German prisoner-of-war camp at Stalag VIIIa, Gorlitz, in 1941.

Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet For The End Of Time will be played by John Lenehan, piano, Sacha Rattle, clarinet, John Mills, violin, and festival director Tim Lowe, cello, in York Minster’s Lady Chapel under John Thornton’s restored 15th century Great East Window (the “Apocalypse Window”). Box office: tickets.yorkminster.org.

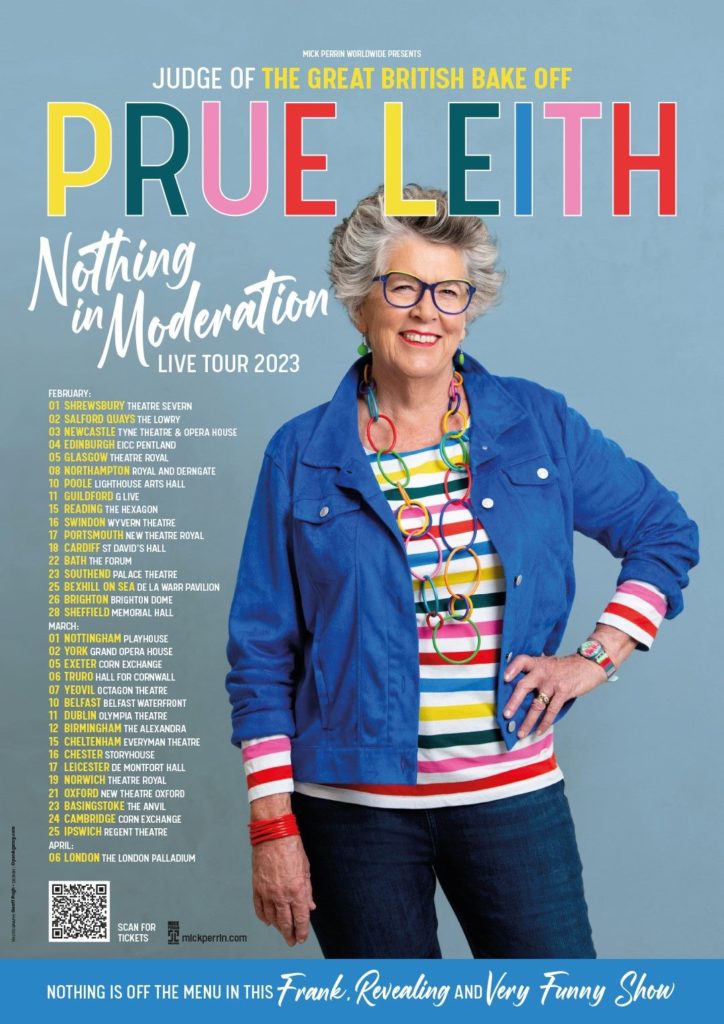

Comedy gig of the week: Burning Duck Comedy Club presents Lloyd Griffith, One Tonne Of Fun, The Crescent, York, Thursday, 7.30pm

AFTER Covid stretched Lloyd Griffith’s last tour to “eight years or so”, he returns with his biggest itinerary to date, One Tonne Of Fun.

Since school, he has always been a show-off, and 20-odd years later, nothing’s changed, so expect stand-up, dubious impressions and a sprinkling of his (incredible) singing from the comic with Ted Lasso, 8 Out Of 10 Cats, Soccer AM, Question Of Sport, Not Going Out and House Of Games credits. Box office: thecrescentyork.com.

Choral concert of the week: Prima Vocal Ensemble, Lift Every Voice, Joseph Rowntree Theatre, York, January 29, 7.30pm

EWA Salecka directs Prima Vocal Ensemble in a life-affirming concert that weaves its way through diverse generations and genres with live accompaniment.

Living composers Lauridsen, Gjeilo, Whitacre and Jenkins sit alongside favourite numbers from Les Misérables and The Greatest Showman, complemented by songs by Annie Lennox, Elbow, the Gershwins and Cole Porter and a tribute to the people of Ukraine. Box office: 01904 501935 or josephrowntreetheatre.co.uk.

Hardcore York gig of the month: Frank Turner & The Sleeping Souls, York Barbican, January 31, 8pm

FRANK Turner, punk and folk singer-songwriter from Meonstoke, Hampshire, will be accompanied by The Sleeping Souls in York as he draws on his nine studio albums from a 17-year solo career.

Last year, the former Million Dead frontman, 41, topped the UK Official Album Chart for the first time with FTHC (his anagram for Frank Turner Hardcore) after his previous four all made the top three. Support slots go to Lottery Winners & Wilswood Buoys. Box office: yorkbarbican.co.uk.

Who was Nellie Bly? In Conversation With Rosemary Brown, York Theatre Royal, February 4, 5.15pm, free admission

YORK Theatre Royal and Tilted Wig’s touring adaptation of Jules Verne’s madcap adventure Around The World In 80 days features not only the fictional feats of Phileas Fogg but also the real-life story of Nellie Bly, American journalist, industrialist, inventor, charity worker and globe-crossing record breaker.

In a free talk, director and adaptor Juliet Forster will be in conversation with Rosemary Brown, author of Following Nellie Bly, Her Record-Breaking Race Around The World, a book inspired by this human rights and environmental campaigner’s aim to put female adventurers back on the map. Box office: 01904 623568 or yorktheatreroyal.co.uk.

The second coming of…York Shakespeare Project, Edward III, rehearsed reading, upstairs at Black Swan Inn, Peasholme Green, York, February 7, 7.30pm

PHASE Two of York Shakespeare Project begins with a staged rehearsed reading of Edward III, the rarely performed 1592 history play now widely accepted as a collaboration between William Shakespeare and Thomas Kyd, replete with its celebration of Edward’s victories over the French, depiction of the Black Prince and satirical digs at the Scots.

Rehearsed readings in February will be a regular part of YSP’s revamped remit to include work by the best of Shakespeare’s contemporaries. Tony Froud’s cast includes Liz Elsworth, Emma Scott and Mark Hird, best known for his work with Pick Me Up Theatre. Tickets: on the door or via eventbrite.com.

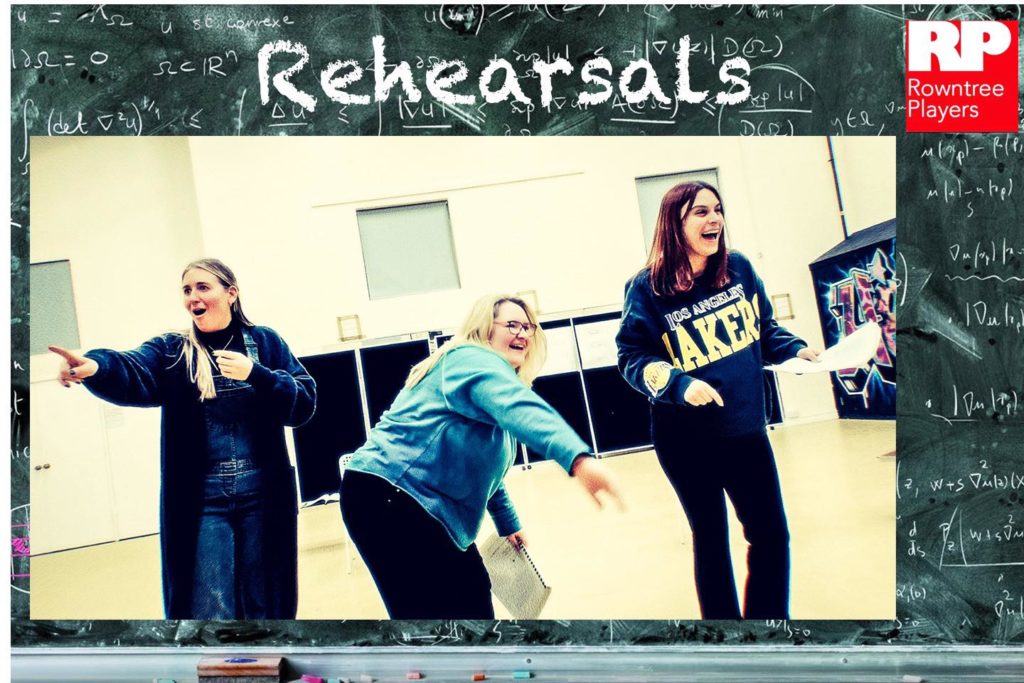

Spring term school play: Rowntree Players in Teechers Leavers ’22, Joseph Rowntree Theatre, York, March 16 to 18, 7.30pm and 2.30pm Saturday matinee

REHEARSALS are underway for Rowntree Players’ production of Teechers Leavers ’22, former teacher John Godber’s update of his state-of-education play, commissioned for £100 by Hull Truck Theatre in 1984.

Actor Jamie McKeller, familiar to York ghost-walk enthusiasts as Deathly Dark Tours spookologist Doctor Dorian Deathly, is working with a cast of Sara Howlett, Sophie Bullivant and Laura Castle as they “put in the hard work needed for this very physically demanding play”. Box office: 01904 501935 or josephrowntreetheatre.co.uk.