AFTER spinning yarns all this week at London’s Charles Dickens Museum, Gothic York actor James Swanton returns home with his Ghost Stories for Christmas.

At the time of going to CharlesHutchPress, only five tickets remain on sale for the entire run.

As last year, Swanton will be performing three Dickens works, one each night, at York Medical Society, Stonegate, from Tuesday to Saturday.

A Christmas Carol on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday will be complemented by the lesser performed The Chimes on Wednesday and The Haunted Man on Friday, all at 7pm.

Swanton, the Outstanding Performing Artist winner in the 2018 York Culture Awards, will be the black-clad gatekeeper for all manner of supernatural terrors after memorising three hours of wintery material for his “seasonal roulette of three Dickensian tales”.

Ahead of his Dickens of a week in York, James answers Charles Hutchinson’s questions.

Why is A Christmas Carol so amenable to being presented in so many guises each winter in York and elsewhere, James?

“Could it be that it’s the greatest story ever written? Ebenezer Scrooge has joined Sherlock Holmes and Count Dracula as Victorian literature’s most endlessly adapted characters.

“But unlike the master detective and the master vampire, who constantly crop up in diverse new contexts, Scrooge remains inseparable from his original story. It’s perfectly structured and passionately written. It demands to be told, just as we all demand to hear it, year after year. There’s a great responsibility not to do it badly!”

What form do your three shows take: a reading or more than that in each one-man show?

“I’m happy to say that these are full-fledged dramatisations rather than Jackanory-style readings. This has been quite the Labour of Hercules: 180 minutes of text to memorise to cover the three one-hour readings! But it’s worth it to ensure these pieces are truly alive. My abridgements are closely based on Dickens’s own performance scripts, so their faith to their sources is absolute.”

Will you use a similar performance style for each tale?

“This is old-fashioned storytelling in a suitably atmospheric space. I’m hoping to use every physical and vocal trick in my repertoire to make the audience see Dickens’s pictures as clearly as I do myself.

“The formidable Miriam Margolyes saw me performing one of these pieces in 2017 at the Charles Dickens Museum. She was very complimentary about its pictorial vividness – and she’s not easily pleased!”

Give quick synopses of The Chimes and The Haunted Man…

“Just like A Christmas Carol, these lesser-known works hinge on disenchanted older men who must encounter the supernatural to change for the better. The Chimes is the exuberant tale of a lowly ticket-porter who finds goblins squatting in the bells of his local church.

“Meanwhile, The Haunted Man is a Gothic chiller about a chemist who hatches a bargain with his ghostly double to remove all of his sorrowful memories.”

Dickens’s concern over Ignorance and Want rings out in A Christmas Carol. Rather than being ghosts, the ills of greed and the need for charity and care for others are as alive as ever. Discuss.

“You know, the absence of Ignorance and Want might be the only flaw in The Muppet Christmas Carol (a near-perfect film, as everyone knows). Dickens spectacularly revives the figure of Ignorance in The Haunted Man, in which the feral child receives a ferocious human embodiment. Deeply disturbing.

“And The Chimes is so socially angry that it might as well be called ‘A Brexit Christmas Carol’. It attacks the untrustworthy press, the still more untrustworthy rich, and a world that condemns the poor without considering how they came to such grief. These might be Victorian ghost stories, but they are indisputably stories for our own age.”

We still respond to what Dickens says in a way that contrasts with so many people turning their back on religion. Why?

“Dickens might be considered to have reinvented Christianity for an increasingly secular world. He’s particularly invested in the idea of redemption, and how it might be realised through the death of an innocent child.

“Death is ever-present for Christ, even at the Nativity: think of King Herod’s massacre of the innocents, or the Wise Man who gifts him with the myrrh that’ll preserve his body after the crucifixion.

“All three of these Dickensian ghost stories centre on children in mortal peril. Tiny Tim must be resurrected just as miraculously as Scrooge. Dickens suggests that we can conquer death, but in ways more practical than waiting for an afterlife.”

James Swanton’s Ghost Stories For Christmas, York Medical Society, Stonegate, York, 7pm nightly; A Christmas Carol, December 17, 19, 21; The Chimes, December 18; The Haunted Man, December 20. Box office: 01904 623568 or at yorktheatreroyal.co.uk

REVIEW: James Swanton in Irving Undead, York Medical Society, Stonegate, York, October 10 to 12 2019

IT starts with a dusty recording of Henry Irving drifting across the York Medical Society carpet.

This is the sound of “the strangest actor who ever lived”, and to a modern ear, the voice is indeed strange and deathly as Irving negotiates a speech from Shakespeare’s Richard III.

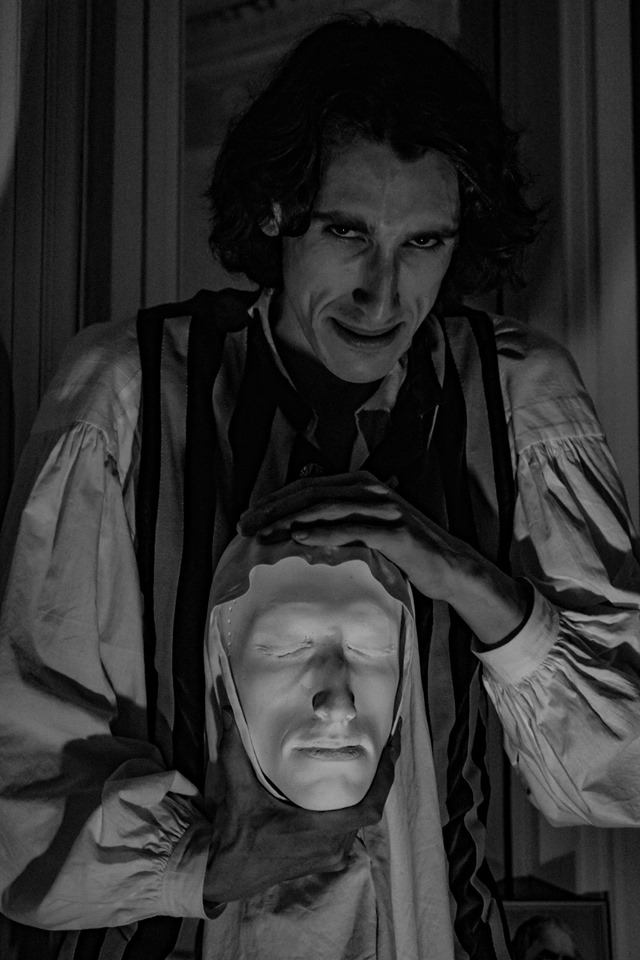

A door opens to the side of the stage, and what first emerges is a thin, long finger of actor-writer James Swanton, then all his digits curl round the door frame. Enter the gaunt Swanton, as spindly of leg as Irving notoriously was.

As ever, whether playing Dracula, Dickens’ Bill Sikes, Frankenstein’s Creature, Lucifer or now Irving, Swanton brings an angular physicality to his bravura performance, wherein he seems to consume the character he plays, so wholly does he take on the part.

As we know too from his solo performance of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol last winter, he is a wonderfully eloquent storyteller, his writing full of intelligence, understanding, wit and drama.

Here Swanton’s Irving relates the story of his life and death, not least how Bram Stoker, his business manager for 20 years is said to have immortalised him by writing the horror story Dracula. The pain behind the mask for the “undead” and restless Irving is that Dracula is now better known than theatre’s first knight: a case of being out for the Count.

Obsessive in his art, ill-fated in love, fearful of scandal, Irving specialised in playing mad monarchs, guilt-stricken murderers and the Devil, delivered with a Gothic, macabre air that apparently “petrified 19th Century London”. Swanton delights in playing Irving’s Romeo, a frightening performance from the early master of horror acting met with derogatory reviews that Irving reads out with a glum glower.

Swanton contends that Irving was a deeply subversive figure with a work, work, work ethic, driven by some mightier force. All this comes through in an intense performance, underscored with admiration for his fellow traveller along theatre’s pit-laden path.

“I hope to do the old man justice,” said Swanton in advance. He certainly does that, while adding to his stock as a formidable talent in his own right.

Charles Hutchinson