Punch Porteous writer Robert Powell and creative practitioner Ben Pugh

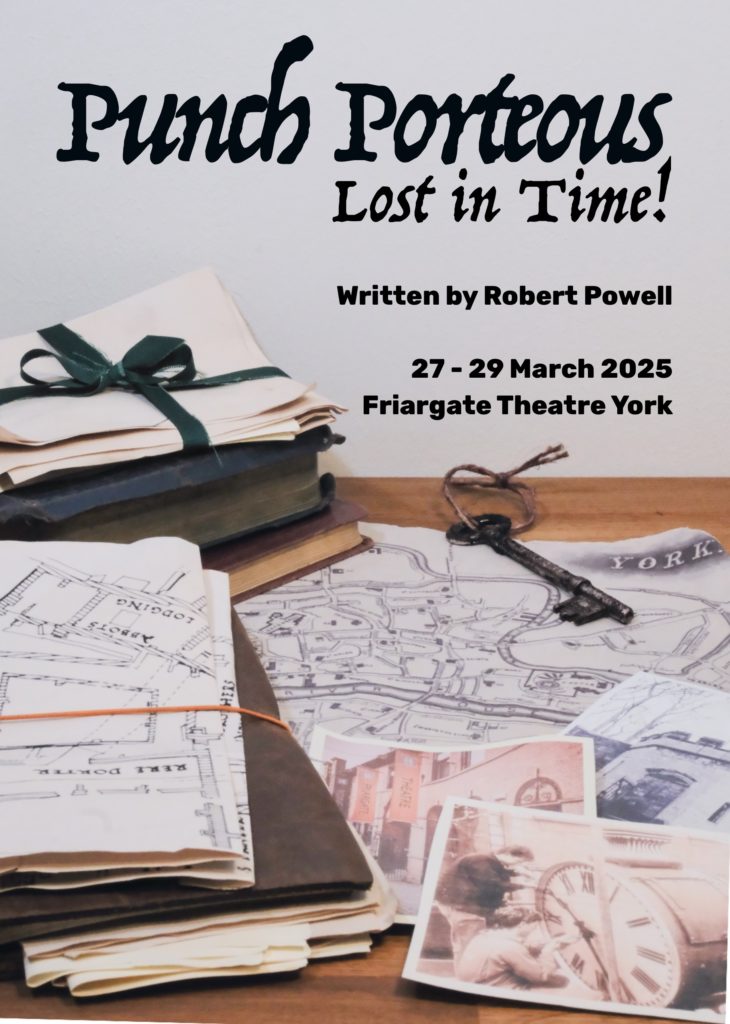

WRITER Robert Powell and creative practitioner Ben Pugh are reviving Punch Porteous – Lost In Time! at Friargate Theatre, York, from tomorrow to Saturday as part of York Literature Festival.

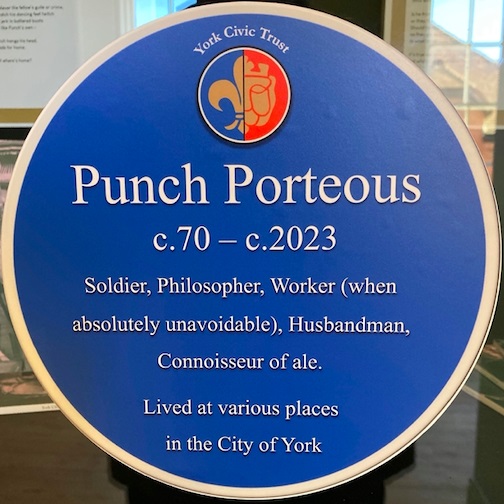

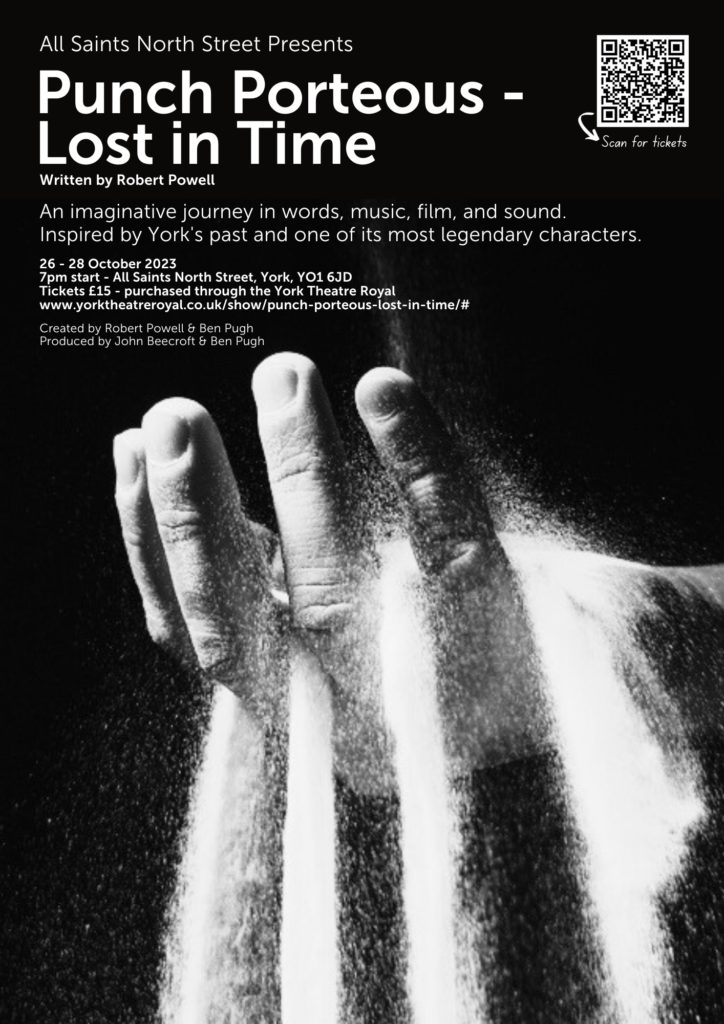

Originally commissioned by All Saints North Street for its October 2023 premiere with support from York Theatre Royal, Powell’s poetic multi-media experience depicts Punch Porteous, a mysterious and ordinary man with an extraordinary predicament, lost in time in York, where he is catapulted unpredictably into different eras from c.70 to c.2025 while the city shape-shifts around him.

“He keeps waking up at various points of the city’s past, dazed and confused, but also with a disturbing knowledge that he’s been there before,” says Canadian-born Robert.

Punch seems to remember Romans, Vikings, Saxons, seeing Henry VIII and meeting Dick Turpin. Now a prophecy says he is to appear at the site of an ancient Friary to find his lost wife Eve – and tell all in Powell and Pugh’s imaginative journey in words, music, film and sound featuring the recorded, “disembodied” voice of York poet Kitty Greenbrown, as well as Powell as Narrator, Nicholas Naidu as Alistair and Imogen Wood as Beatrice.

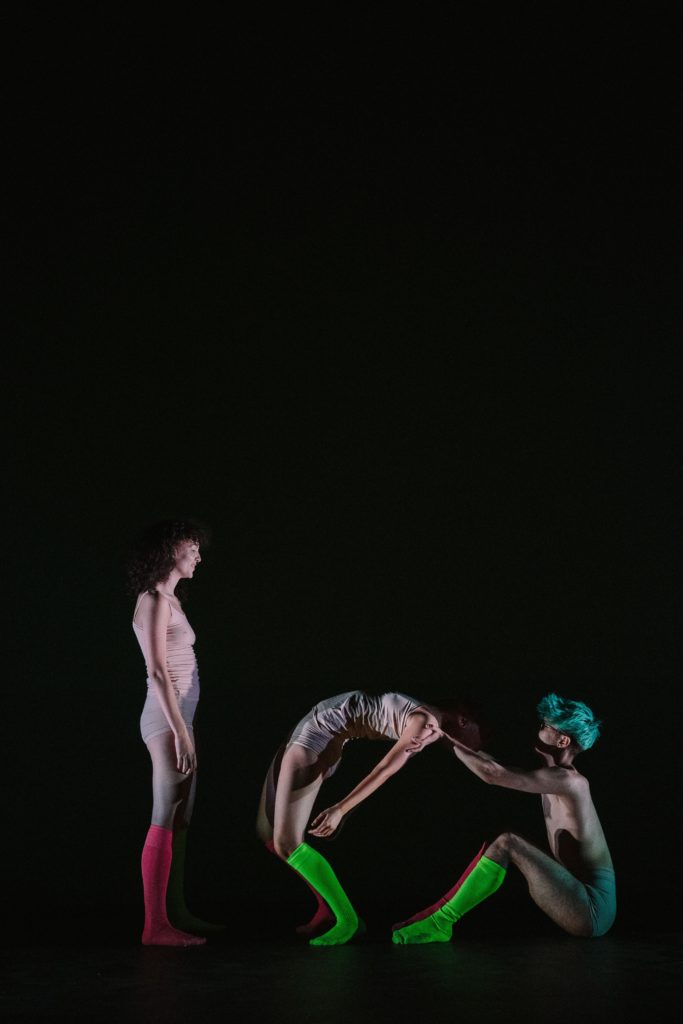

Nicholas Naidu, as Alistair, and Imogen Wood, as Beatrice, in Punch Porteous – Lost In Time! Picture: Ben Pugh

Inspired by the history of York, Robert first recounted a story of Punch in his poem Punch Porteous Goes To York Races, with further poetic stories in his 2023 commission for York Civic Trust, Time Town, Some Poems Of York.

“We’re totally delighted to be bringing Punch back,” says Robert. “I thought Punch had some more breath left in him after All Saints and we had the sense that there was more of an audience to see it.

“Friargate Theatre is an artistic asset to York with new management, and what better place could we find to stage it: a theatre space, rather than a church, though it was the church [All Saints North Street] that commissioned it, and the church provided a rich, deeply resonant space.

Kitty Greenbrown: Lending her voice to this week’s performances of Punch Porteous – Lost In Time!

“We’re also delighted to be taking part in York Literature Festival, which I was part of for a long time. We talked to Friargate Theatre first, absolutely the right place for it, and then approached the festival about featuring a piece based on poetry, and they responded very positively, especially when you consider they don’t usually have plays.”

Robert has re-written his drama to take in the history of the Friargate Theatre site as a friary. “We now have Punch ‘predicting’ that it was friarage from the tenth century up until Henry VIII’s boys tore it apart, leaving only the wall along the river. We will now be reopening the Friarage, with Punch determined to get there from Baile Hill.”

How will the audience experience differ from the All Saints premiere? “I think that being in a theatre space, rather than a church, the audience will need to use their imagination more, and we will need to work their imagination more to imagine the historic buildings of York, whereas previously we had the incredible prop of the church building,” says Robert.

Robert Powell in his role as Narrator for Punch Porteous – Lost In Time! Picture: Ben Pugh

“Now we have to use our ‘prop’ box to bring to life this semi-visible everyman who had bumped into some famous people but mainly lived among the ordinary people of York, creating that sense of Punch being grounded and having a working man’s sensibilities.”

Describing Punch’s character, Robert says: “He’s comic but serious; he gets drunk but is very philosophical. He’s seen a lot and suffered a lot, as the people of York have.

“With Dick Turpin, for example, what happens is that he becomes like a fairytale figure, but in Punch Porteous, Punch remembers attending Turpin’s public execution, seeing the horror of his feet turning in the air, so I’ve tried to bring the harsh reality to folk tales. Turpin’s death would have been horrendous.

“In Punch Porteous, I’m conveying the friction between the heritage myth and the darker reality that people have had to live with in York over the centuries.

The poster for Punch Porteous – Lost In Time at Friargate Theatre, York

“It’s a story told in a somewhat different way from the historical, heritage way that the story of the city is so often told. So, in a sense, without being too heavy about it, I wanted to disrupt that norm, to think about history from the ‘ordinary’ perspective that most of us experience it from.

“Writers can bring an understanding of history where I think there’s a role for the imagination that runs parallel with the facts. It’s not enough to have the testimonies and the photographs. You need your imagination to bear witness. Hilary Mantel thought a lot about this, about the role of fiction to engage with people, as opposed to documentary evidence. Where documentary leaves off, the imagination takes over, but rooted in experience.”

Robert loves the experience of walking through York, “passing through veils, where one minute you are in the 21st century, and then in the past”. “As a Canadian boy, from an early age, I had a hunger for what York offered,” he says. “Here I am, this little kid in Ottawa, digging in the fields next door, hoping to find Roman remains, so I had to come to York to do that. It’s been a very personal journey for me, and York gives you that in a very intense way.

“What is a Canadian doing fooling around with York’s precious history? To me, from that perspective, as a writer, it’s a heavenly place to be, and as a writer, I’m fascinated by time. Punch Porteous is a great opportunity to have someone who slips and slides through York and time, and so though I’m not originally from York, I hope it has resonance for true Yorkists.”

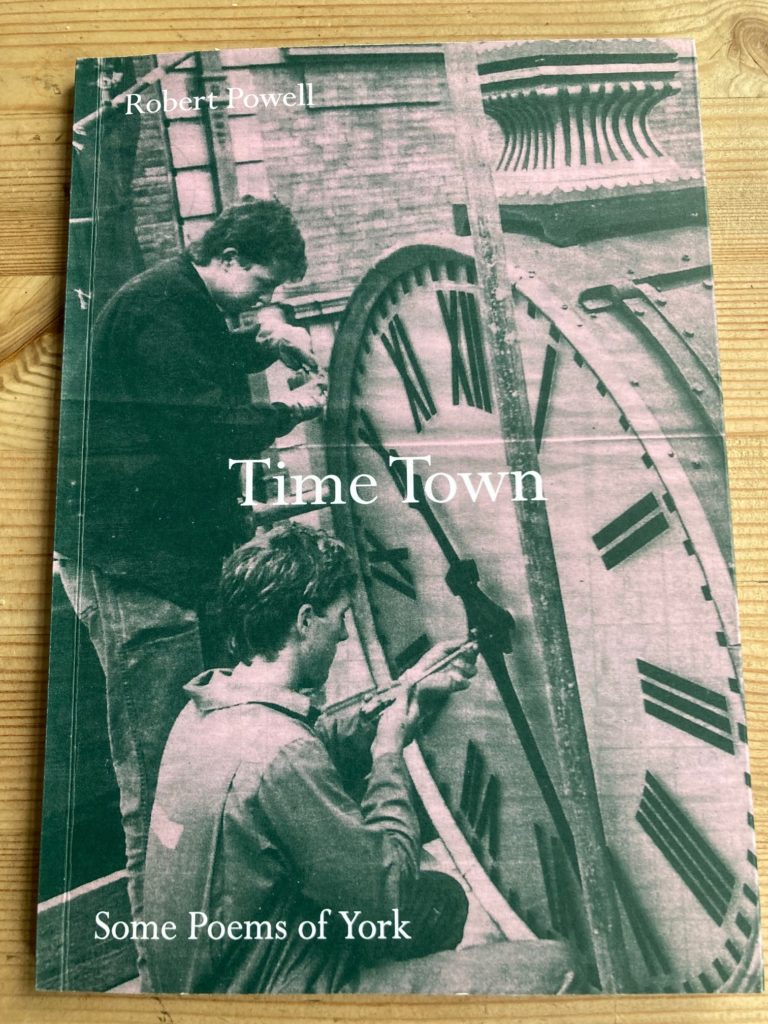

The cover to Robert Powell’s latest poetry collection, Time Town, Some Poems of York

Punch Porteous may have further life beyond this week’s performances. “I’ve had this niggling thought that might bring a further bit of spark to the exercise,” says Robert. “Was Punch Porteous a real person?

“Since my tales of Punch were inspired by a story told to me about an actual York man called Punch Porteous in the 1920s, who won a small fortune at York Races, it would be fun to ask The Press readers if they’ve ever heard of such a person. I would love to hear from you and I can be reached at https://www.rjpowell.org/.

“I would love Punch Porteous to become one of the urban myths of York and hopefully we are moving in that direction.”

York Literature Festival presents Punch Porteous – Lost In Time!, Friargate Theatre, Lower Friargate, York, tomorrow until Saturday, 7pm plus 2pm Saturday matinee. Box office: ticketsource.co.uk.

For Ben Pugh’s film trailer of Punch Porteous – Lost In Time!, head to: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/ky2ym8uovcqisjmyahpjt/Punch-Trailer-1.mov?rlkey=0twzzrbektny13v2tu3oe2hkz&dl=0

Robert Powell: Writer, curator and cultural consultant with background in the arts, place-making, photography and journalism. Picture: Owen Powell

Robert Powell: the back story

WRITER, curator, and cultural consultant with more than 40 years’ experience in the arts, built environment, community engagement and media in England, Scotland and his native Canada.

Director of Stills Gallery of Photography in Edinburgh from 1986 to 1989. Worked for Canada Council for the Arts from 1989 to 1997.

Director of Beam, arts, architecture and education charity in Wakefield, from 1997 to 2015, working with many leading artists, architects, and urban designers.

Established Wakefield Lit Fest, festival of reading & writing, in 2012. Made Honorary

Fellow of RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) in 2017.

Robert’s creative writing has been published widely in Canada and UK. Since 2007, produced five poetry collections, plus performances and film-poems inspired by buildings, rivers and other places.

In 2018, artist in residence with Kone Foundation at Saari, Finland. In 2019, undertook community-based artistic project on Irish border during Brexit negotiations.

In 2023-24, writer in residence with York Civic Trust. Wrote and performed in Punch Porteous – Lost In Time!, poetic drama inspired by history of York, at All Saints North Street.

Resident in York for ten years, based in South Bank. Latest publication, Time Town, Some Poems of York, features poetry about a Georgian museum and a man lost in time from his York Civic Trust residency.

The first knock-out Punch poem by Robert Powell: Punch Porteous Goes to York Races

ONE Saturday afternoon, in summer 1930,

at York Races, Punch won a fortune, £17,

tramped back into town, bought a tin hip bath

and took it to the Red Lion, where Uncle John’s wife Rose

was publican and the boatmen-gypsies supped;

required of John to fill it full with drink, then

helped him and two others lurch it, slopping

on cobbles in the early evening light,

to the tram stop, calling on all and sundry

Come take wine with me!

though in truth it was ale;

and cupping its contents for free

to drivers, passengers, passers-by;

and the bath, once emptied,

by a drunken Punch

tossed into the Foss.

Gaze down from the bridge, they say,

in certain light, on certain days,

in the shallows, in the depths,

you can still see it,

among the vagrant

shopping carts,

the swans.

© Robert Powell