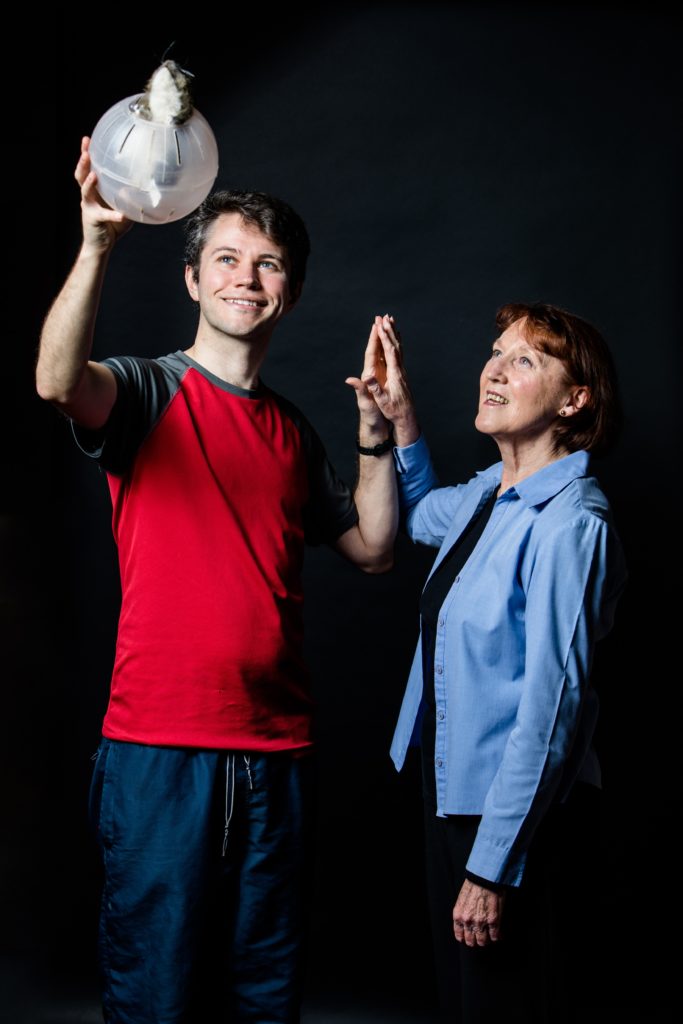

Setting sail in Pick Me Up Theatre’s Anything Goes: Reno Sweeney (Alexandra Mather, front centre) and her Angels, Sophie Curry, left, Chloe Branton and Sophie Kemp. Picture: Felix Wahlberg

DITCH the December chills in York and climb aboard the S.S. American as Pick Me Up Theatre’s all-singing all-dancing Christmas production of Anything Goes! sets sail at Theatre@41, Monkgate, York, on December 12.

Directed by Andrew Isherwood, Cole Porter’s swish musical follows the madcap antics of a motley crew as they chart their course from New York to London on a Christmas-themed steamer.

On board are popular nightclub singer/evangelist Reno Sweeney (Alexandra Mather) and her pal, lovelorn Wall Street broker Billy Crocker (Adam Price), who has stowed away on board in pursuit of his beloved Hope Harcourt (Claire Gordon-Brown).

Hope, however, is engaged to another passenger, English gent Sir Evelyn Oakleigh, played by Neil Foster, who is reprising the role after 27 years. “It’s amazing how I’ve remembered so many of the lines and lyrics,” he says. “They must have been buried somewhere in my memory.”

Sailing to England too is second-rate conman Moonface Martin (Fergus Powell), aka “Public Enemy #13”. Song, dance and fabulous farce ensue as Reno and Moonface try to help Billy win the love of his life.

Reno will be Alexandra Mather’s first lead in a musical after principal roles aplenty for York Opera. “Taking on Reno Sweeney is incredibly exciting for me,” she says. “I’m stepping into such a sharp and charismatic role, which is a dream come true.

“With Cole Porter’s music and the brilliant, witty script, the whole experience feels nostalgic, stylish and incredibly glamorous.”

“I’m stepping into such a sharp and charismatic role, which is a dream come true,” says Alexandra Mather of playing Reno Sweeney in Anything Goes

That pretty much sums up Susannah Baines and Beryl Nairn too, who will be sharing the sassy role of Hope’s mother, Evangeline Harcourt. No strangers to a sequin and a spin around the dance floor, they cannot wait to take to the stage at Theatre@41.

“It’s a fantastic role and I’m honoured to be sharing it with such a great, talented friend,” says Susannah. “I just feel for the rest of the cast, dealing with two overbearing mothers! I love this era. It’s so elegant. And I’m really enjoying working with our choreographer Ali Kirkham.”

Ali is right at home with her role, not only as choreographer but also with the nautical setting of this musical. “I worked as a singer myself on cruise ships,” says the former head of musical theatre at Kirkham Henry Performing Arts in Malton.

“I produced shows for more than 20 years for the fabulous Fred Olsen liners and theatres around the world. Many of my ex-students have gone on to perform on the West End and Broadway, in television and films, and of course on top-class cruise lines. Like my former student Charlie Fox, who is joining our York cast between contracts.”

The full cast comprises: Alexandra Mather as Reno Sweeney; Adam Price, Billy Crocker; Neil Foster, Lord Evelyn Oakleigh; Fergus Powell, Moonface Martin; Claire Gordon-Brown, Hope Harcourt; Beryl Nairn/Susannah Baines, Evangeline Harcourt; Mark Simmond, Elisha Whitney, and Adrian Cook, Ship’s Captain.

Thea Fennell plays Erma Latour; Leo Portal, Ship’s Purser; James Robert Ball, Minister/Sailor; Zachary Thorp, Spit; Reuben Baines, Dippy; Chloe Branton, Angel; Sophie Curry, Angel; Charlie Fox, Sailor, and Sophie Kemp, Angel. Cameo roles go to Ryan Richardson, Rich Musk, Andrew Roberts, Sanna Jeppsson, Adam Sowter and Jim Paterson.

The creative team comprises director Andrew Isherwood; musical director John Atkin; sound and lighting designer Will Nicholson; choreographers Ali Kirkham and Robert Readman (who also handles design and production) and wardrobe mistress Julie Fisher, assisted by Jo Hird.

Pick Me up Theatre in Anything Goes, Theatre@41, Monkgate, York, December 12 to 30. Performances, 7.30pm December 12, December 15 to 18, December 20 and December 27 to 30; 2.30pm, December 13, 20, 21 and 27. Box office: https://tickets.41monkgate.co.uk/seasons/b4dda860-03cd-492d-b990-026e1ec590a3