THE 2022 Ryedale Festival will embrace 300 performers in 52 concerts from July 15 to 31, kicking of the event’s fifth decade of inspiring performances in beautiful North Yorkshire locations.

Under Christopher Glynn’s artistic directorship, the festival will find a special place for Handel’s music, including a pop-up production of his magical opera Acis And Galatea that will visit three churches.

The music and legacy of Ralph Vaughan Williams will be in focus too, as will the genre-blending elan of Errollyn Wallen and the 50th anniversary of Swedish supergroup Abba.

The Kanneh-Mason family will open the festival on July 15 with a concert by the seven brothers and sisters from Nottingham, aged between 11 and 24. On July 16, Kadiatu Kanneh-Mason will be in conversation with Edward Seckerson in House of Music: Raising The Kanneh-Masons, a joyful celebration of this extraordinary musical story.

Six world premieres will take centre stage. Julian Philips will mark the 150th anniversary of the birth of Vaughan Williams with Looking West, a new work inspired by the ancient stories and landscapes of northern England.

Roxanna Panufnik’s Babylonia will go on an imaginative journey to the Middle East, while Errollyn Wallen and Tarik O’Regan will explore the myth of creation in their co-composed work Ancestor, to be premiered by Philharmonia Baroque.

Joseph Howard’s community song cycle Seven Mercies celebrated the heritage and talent of Pickering on May 21; Robert Balanas will be debuting an ABBA medley for solo violin, and Callum Au will be bringing a new work co-commissioned with Spitalfields Festival.

A strong line-up of artists in residence will be in Ryedale for the festival. Baritone Roderick Williams will lead two of the four concerts marking Vaughan Williams’s anniversary with Christopher Glynn and fellow artists in residence the Maxwell Quartet, as well as leading a singing masterclass with talented young artists. The Gesualdo Six will perform two vibrant programmes in Ampleforth Abbey and Castle Howard.

The festival’s two ensembles in residence, the National Youth Choir of Great Britain and San Francisco’s Philharmonia Baroque (in their first UK tour for more than a decade), will present one of Handel’s Dixit Dominus, a tour-de-force of vocal and instrumental virtuosity that bubbles with the energy and exuberance of youth.

Ryedale Festival Young Artists will be in the spotlight too. Violinist Roberts Balanas will perform a late-night candlelit concert, while Scottish accordionist Ryan Corbett will set out on a “troubadour trail” across Ryedale, bringing music – from the grandeur of Bach to the romance of Tchaikovsky – to beautiful and little-known churches across the region.

Soprano Siân Dicker and pianist Krystal Tunnicliffe will create a relaxed, informal and interactive concert for people living with dementia, their friends, family and carers – and anyone else who would like to attend. Bassoonist Ashby Mayes will collaborate with Krystal Tunnicliffe in an enterprising programme at a coffee concert.

Further highlights will include the London Mozart Players with pianist conductor Martin James Bartlett; The National Youth Choir of Great Britain performing a programme on the theme of environment; Pete Long and Friends playing 100 Years Of Jazz In 99 Minutes and fast-rising soloists such as violinist Johan Dalene, cellist Bruno Phillipe, trumpeter Lucienne Renaudin Vary, harpsichordist Richard Egarr and pianists Rebeca Omordia and Alim Beisembayev. Renaudin Vary will give a brass masterclass too.

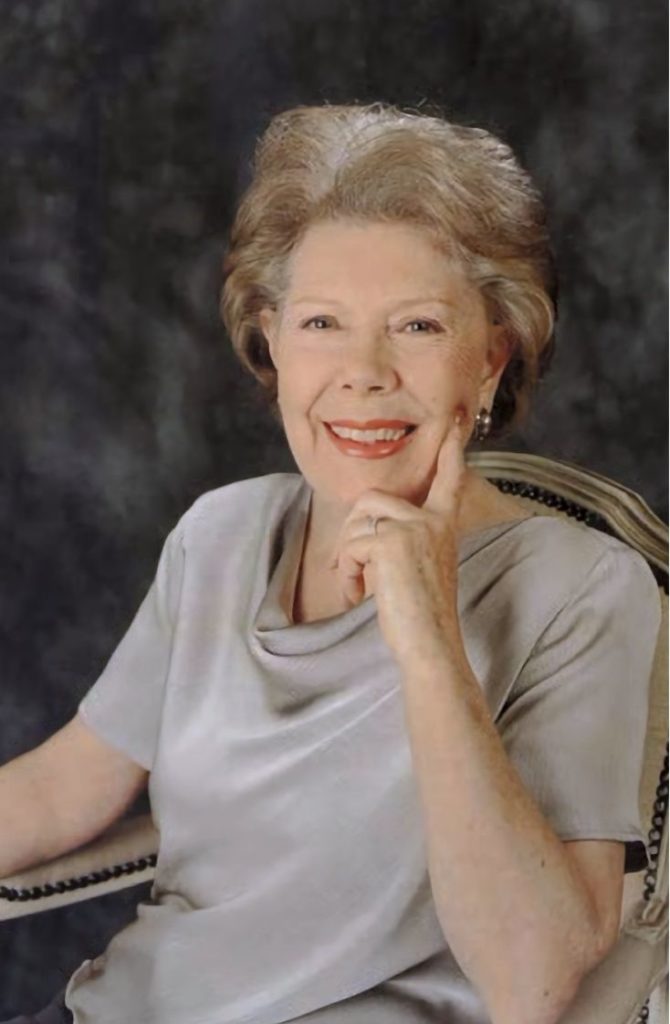

Dame Janet Baker will be in conversation with Edward Seckerson and a visit from poet, author and broadcaster Lemn Sissay will be among the literary events. Family concerts will include a musical version of the modern children’s classic Izzy Gizmo.

For the final gala concert, trumpeter Lucienne Renaudin Vary will join the Royal Northern Sinfonia for a sunny-spirited concerto at the heart of an eclectic programme that will take in lyricism of two English romantics, a Bach-inspired work by Errollyn Wallen and one of Haydn’s most rousing and witty symphonies.

A new partnership with the Richard Shephard Foundation is working in primary schools to transform the festival’s engagement with children across Yorkshire. Already this has supported Seven Mercies, a new Community Song Cycle by Joseph Howard and Emma Harding at the Church of St Peter and St Paul, Pickering, on May 21. Inspired by the church’s famous murals, this celebration of local heritage and talent took the theme of countering difficult times through small acts of kindness.

Seven Mercies is one of two major elements of the festival taking place outside the main festival in July. Post festival, on October 29, the Hallé Orchestra and Chorus, Natalya Romaniw, Alice Coote, Thomas Atkins, James Platt and conductor Sir Mark Elder will perform Verdi’s mighty and dramatic Requiem in York Minster.

First-time ticket-buyers can attend selected events for £10, under-18s for £5. All are invited to watch the free-to-view additional content that will be shared on the digital platform RyeStream.

Artistic director Christopher Glynn says: “From legendary artists such as Dame Janet Baker to stars of the new generation like the Kanneh-Masons, we’ve brought together a line-up of international quality to perform in stunning locations across the beautiful area of Ryedale, from historic old churches to magnificent stately homes.

“As always, the festival is a celebration of music and place, and how they can enhance each other. I’m especially pleased that we are working with the Richard Shephard Music Foundation to bring musical opportunities to primary school children across Yorkshire, and that hundreds of tickets will be available from as little as £5 for under-18s and first-time attenders. We look forward to welcoming music-lovers from far and wide to Ryedale this summer.”

For full details, go to: ryedalefestival.com. Box office: 01751 475777; ryedalefestival.com; in person from Memorial Hall, Potter Hill, Pickering, second floor, Monday, Tuesday and Thursday, 9.30am to 2.30pm.

2022 Ryedale Festival programme

July 15, 7pm, St Peter’s Church, Norton

Opening Concert

Kanneh-Mason Family

July 16, 3pm, St Michael’s Church, Malton

House of Music: Raising the Kanneh-Masons

Kadiatu Kanneh-Mason

July 16, 8pm, St Mary’s Priory Church, Old Malton

Johan Dalene, violin

Charles Owen, piano

July 17, 3pm, Helmsley Arts Centre

Family Concert

July 17, 7pm, Duncombe Park

Pre-concert talk: Katy Hamilton

July 17, 8pm, Duncombe Park

The Wanderer

Roderick Williams, baritone

Christopher Glynn, piano

July 18, 11am, Helmsley Arts Centre

Shakespeare’s Infinite Variety

Lucy Beckett, speaker

July 18, 3pm to 5pm, Helmsley Arts Centre

Roderick Williams, masterclass

July 18, 7pm, Sledmere House and Church

Double Concert

July 19, 11am, All Saints’ Church, Slingsby

The Maxwell Quartet

July 19, 2pm, All Saints’ Church, Helmsley

Pre-concert talk

Katy Hamilton

July 19, 3pm, All Saints’ Church, Helmsley

Acis And Galatea I

July 19, 9.30pm, The Milton Rooms, Malton

Late-Night Folk

July 20, 11am, Birdsall House

Margaret Fingerhut, piano

July 20, 3pm, St Mary’s Church, Lastingham

Acis And Galatea II

July 20, 7pm, Church of St Peter and St Paul, Pickering

Pre-concert talk

Katy Hamilton

July 20, 8pm, Church of St Peter and St Paul, Pickering

Mystical Songs

Roderick Williams & The Maxwell Quartet

July 21, 11am, St Nicholas Church, Husthwaite

Troubadour Trail I

Ryan Corbett, accordion

July 21, 3pm, St Michael’s Church, Malton

Acis And Galatea III

July 21, 8pm, Birdsall House

Bruno Phillipe, cello

Tanguy de Williencourt, piano

July 22, 1pm, Church of St Martin-on-the-Hill, Scarborough

National Youth Choir

July 22, 3pm, St Hilda’s Church, Sherburn

Troubadour Trail II

Ryan Corbett, accordion

July 22, 8pm, The Milton Rooms, Malton

100 Years Of Jazz In 99 Minutes

Pete Long and Friends

July 23, 11am, Holy Cross Church, East Gilling

Troubadour Trail III

Ryan Corbett, accordion

July 23, 3pm to 5pm, The Milton Rooms, Malton

Come and Sing ABBA!

July 23, 8pm, St Peter’s Church, Norton

London Mozart Players

July 24, 3pm, James Holt Concert Hall, Kirkbymoorside

Kirkbymoorside Town Brass Band

July 24, 6.30pm, All Saints’ Church, Kirkbymoorside

Alim Beisembayev, piano

July 24, 9.30pm, All Saints’ Church, Kirkbymoorside

Late-Night Candlelit Concert

Roberts Balanas, violin

July 25, 11am, All Saints’ Church, Hovingham

Rebeca Omordia,piano

July 25, 2pm, Hovingham Hall

National Youth Chamber Choir

Philharmonia Baroque

July 25, 7.30pm, Duncombe Park

Dame Janet Baker

In conversation with Edward Seckerson

July 26, 11am, St Lawrence’s ’s Church, York

Music For A While

Rowan Pierce & Philharmonia Baroque

July 26, 8pm, Ampleforth Abbey

The Gesualdo Six

July 27, 11am, St Michael’s Church, Coxwold

Lucienne Renaudin Vary, trumpet

Félicien Brut, accordion

July 27, 7pm, Castle Howard

Triple Concert

July 28, 11am, St Oswald’s Church, Sowerby

Ashby Mayes, bassoon

Krystal Tunnicliffe, piano

July 28, 3pm, The Milton Rooms, Malton

Dementia-friendly Concert

Siân Dicker, soprano

Krystal Tunnicliffe, piano

July 28, 7pm, Duncombe Park

Stephen Kovacevich, piano

July 28, 9.30pm, St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale

Late-Night Candlelit Concert

Richard Egarr, harpsichord

July 29, 11am, St Peter’s Church, Norton

Inner City Brass

July 29, 3pm to 5pm, James Holt Concert Hall, Kirkbymoorside

Brass masterclass

Lucienne Renaudin Vary

July 29, 7pm, St Peter’s Church, Norton

A Garden Of Good And Evil

Philharmonia Baroque

July 30, 11am, All Saints’ Church, Hovingham

Siân Dicker, soprano

Krystal Tunnicliffe, piano

July 30, 3pm, The Galtres Centre, Easingwold

Lemn Sissay

My Name Is Why

July 30, 6pm, Church of St Peter and St Paul, Pickering

Pre-concert talk

July 30, 7.30pm, Church of St Peter and St Paul, Pickering

Looking West

July 31, 3pm, The Worsley Arms, Hovingham

Jazz in the Garden

July 31, 5pm, All Saints’ Church, Hovingham

Festival Service

July 31, 6.30pm, Hovingham Hall

Final Gala Concert

Royal Northern Sinfonia

Lucienne Renaudin Vary, trumpet

Post-festival concert: October 29, 7.30pm, York Minster

Hallé Orchestra and Chorus

Verdi: Requiem

Natalya Romaniw, soprano

Alice Coote, mezzo-soprano

Thomas Atkins, tenor

James Platt, bass

Sir Mark Elder, conductor