ARE people really aware of the dangers of polluted air close to home in York, ask arts researcher, educator and cyclist Clare Nattress and atmosphere scientist Dr Daniel Bryant?

Their studies are the subject of a collaborative exhibition under the title of The Art Science Interface: Making York’s Air Pollution Visible, on show at Blossom Street Gallery, York, with project support from the National Environmental Research Council.

“The work shines a light on the air pollution experienced in York while cycling with the objective of making the invisible, visible,” says conceptual artist and University of York St John graphic design lecturer Clare, whose white-painted, pollution-splattered, unwashed bike forms the exhibition centrepiece.

The same Bombtrack Beyond +1 German bike on which Clare had cycled around six countries – Norway, Germany, Spain, then Nepal, and onwards to Australia and New Zealand – in ten months in 2018 when taking a break from work and study as she approached 30.

“Pollution is a hot topic at the minute and a pressing global issue. Air pollution causes serious health risks and costs to the NHS could reach £5.3 billion,” she says.

“Recently I was in the company of air pollution activist campaigner Rosamund Kissi Debrah, who lost her daughter to asthma, the first registered UK resident to have air pollution as her cause of death.”

Airborne particulate species less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter, known as PM2.5, are considered to be the most deadly form of air pollution, contributing to millions of premature deaths per year globally.

“However, due to the small size of these damaging airborne particulate species, drawing public attention to the issue is challenging,” says Daniel, from the University of York’s Wolfson Atmospheric Chemistry Laboratories, who has worked alongside Professor Jacqui Hamilton. “Our study aims to increase public awareness of PM2.5 through our art-science collaboration.”

Clare has used her bicycle as a performative tool to pedal on low and high infrastructure routes around the City of York – where the roads around the circumference of the University of York and York St John University are highly polluted areas often blighted by heavy congestion – to investigate if there are striking differences in air pollution levels and chemical composition, depending on the routes.

Clare’s bicycle was equipped with a miniature aerosol sampler and air quality sensor to gather street-level data over the course of three months as she cycled up to five hours per ride in urban and rural locations within York and the surrounding areas with a focus on six commuter/bus routes to and from the universities.

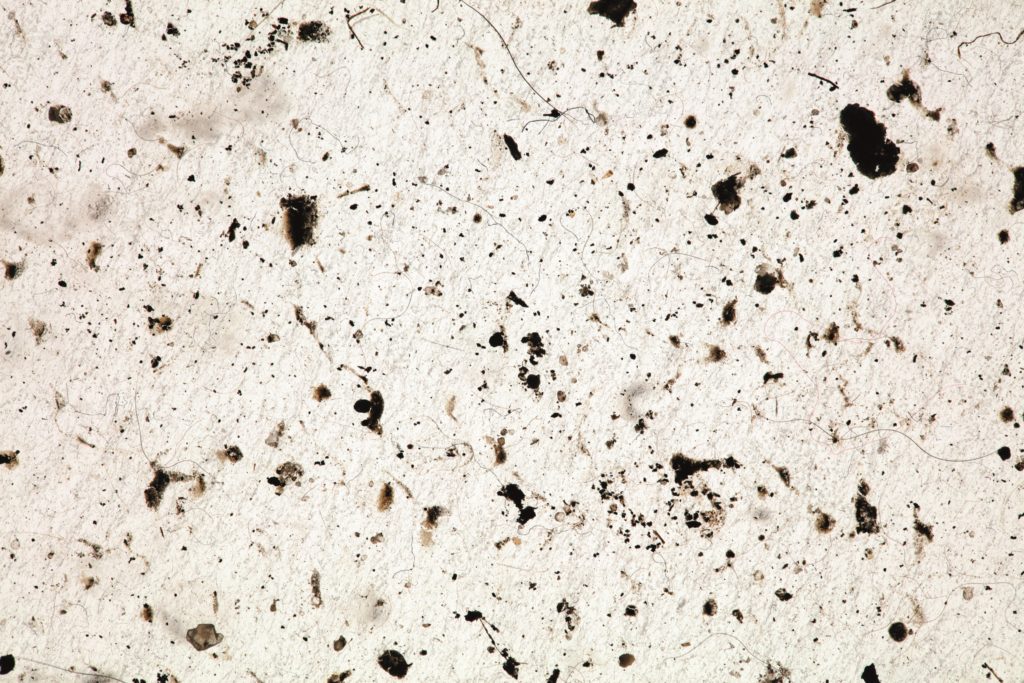

The filters collected were extracted and analysed by Daniel through an established method used for PM2.5 filter samples, using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography, high-resolution mass spectrometry to identify known compounds within the samples.

The process of collection and extraction were documented, and the filters also photographed and investigated under a microscope by Daniel.

The data and information gathered have been incorporated onto a digital map of York to reveal collection locations and routes, as well as pollution concentrations and compounds present within filter samples.

“Combining this data with photographs and video snapshots of each performance ride will improve the public’s ability to see for themselves pollution within their city,” says Clare, whose work forms part of her own Digital Smog project, hence the involvement of her partner, Matt Waudby, as photographer and videographer.

His photography, by the way, featured in an exhibition at Cycle Heaven, where he works, during the 2021 York Design Week.

“As an artist, I’m interested in the embodied experience of bicycling using theories of performativity and materiality,” says Clare. “The body becomes a site for academic enquiry. How does the body attune to air pollution? Can we smell it and can we taste it? How does it interact with our bodies while cycling? This other than human collaborator is interconnected with our bodies; we are intertwined.”

Clare and Daniel’s interdisciplinary, frontier-pushing partnership has increased their understanding of environmental hazards that face cyclists and the benefits of a healthier environment through improved infrastructure.

“This study has been beneficial to help monitor and creatively disseminate exactly what cyclists and the public are exposed to and will help to inform effective solutions,” says Clare.

“Despite ongoing evidence that suggests art enhances our understanding of science and data, there’s still much to analyse regarding impact and personal realisation for action.

“This research project and resulting exhibition provide initial evidence that the public engages with creative and visual outcomes that aim to make the invisible, visible.”

Clare and Daniel’s research project comes against the backdrop of between 28,000 and 36,000 deaths every year in the UK being attributed to human-made air pollution.

“But it’s very difficult to pinpoint because everyone is subjected to it,” says Daniel. “It’s like how you could smoke all your life and not die from cancer, or you could smoke only one cigarette but die from cancer.

“The whole point of the project is to highlight pollution visually, especially to make you think if you’re travelling in a car.”

Clare points out: “Pollution is worse if you’re sitting in a car in traffic, whereas a cyclist or pedestrian is not exposed in the same way because they’re on the move. In a car, you’re in a hot box for pollution.”

Daniel rejoins: “Pollution levels vary, depending on the weather, the temperature, the time of year, the day of the week, the density of traffic. What we do know is that idling in traffic is a big issue in a small city like York where you have to stop a lot, deal with the one-way systems, and everyone trundles along Gillygate, for example.”

Clare adds: “In terms of smelling it, Rougier Street is the worst, the most pungent. That’s because it’s ‘bus central’.

“Look at what’s happening in York. In Gillygate, where Wackers [fish and chips restaurant] is being turned into flats, they’ve been told to keep windows shut…because of the air pollution.”

Clare’s cycling is powering her PhD studies in the School of Art at Leeds Beckett University. Here is the snappy thesis title: “How can cycling be a performative methodology to investigate, reveal and disseminate the problem of air pollution?” As Freddie Mercury once exclaimed, the answer is: “Get on your bikes and ride”.

In practical terms, Clare has learned: “There are cheap, affordable sensors that you can buy to attach to your cycle or backpack to record your exposure, and I now choose my cycling routes more carefully, going on longer routes to avoid pollution,” she says.

York likes to portray itself as the city of cycling. “York is lucky that it has the two rivers [the Ouse and the Foss], with all those cycle paths, but if you took the rivers out of York, it wouldn’t really be a cycling city, with all that heavy traffic,” says Clare bluntly.

Looking at the art and science interface from the artistic perspective, she welcomes the chance to make her Blossom Street Gallery debut with conceptual work that “sits differently to the art it’s positioned alongside, so hopefully it brings a new audience there”.

To prove the point, invitations to the opening private view were extended to the cycling community, scientists and lecturers interested in air pollution, as well as York’s creative network and artists.

Daniel has welcomed the opportunity for collaboration between different disciplines at York’s universities. “Before this work, I would never have thought of doing a project like this. If I just did it for a journal, no-one in the wider public would see it, but the Blossom Street Gallery exhibition makes that possible,” he says.

“We’re now looking for further funding to expand the interface. If we get it, we would look to purchase sensors to make them available for commuters and hobby cyclists to get a breadth of pollution research material and then upload the data.”

Clare adds: “We would also look to run workshops, getting people together from different industries to really look at where pollution is worst in York and what can we do about it.”

The Art Science Interface: Making York’s Air Pollution Visible runs at Blossom Street Gallery, York, until June 30.

The science bit:

Particulate Matter 1, 2.5 & 10. (PM1, PM2.5 & PM10)

PMs are small solid particles that can penetrate into the lungs with the finest ones even binding to blood vessels. PM10 refers to particles smaller than 10 microns in diameter or a tenth of the width of a human hair. PM2.5 are those smaller than 2.5 microns.

PMs can come from road traffic, energy consumption and natural phenomenons such as volcanic eruptions. PMs can change according to wind speed, weather and temperature, often settling in locations with a lack of wind.

Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2)

NO2 is a suffocating gaseous air pollutant formed when fossil fuels such as coal, oil, gas or diesel are burned at high temperatures. 50 per cent of NO2 emissions are due to traffic.

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)

VOCs are a combination of gases and odours emitted from many different toxins and chemicals found in everyday products. These can include household paint, new furniture, candles, cooking, cleaning and craft products as well as beauty products and cosmetics. They can also be emitted by traffic and industries. Some VOCs are classified as carcinogenic. (Plume Labs, 2022).

The funding bit:

THE Art Science Interface: Making York’s Air Pollution Visible is one of three projects to share a £76,000 grant from the NERC Discipline Hopping for Environmental Solutions grant awards.

Did you know?

YORK has the highest rate of bicycle thefts in England.