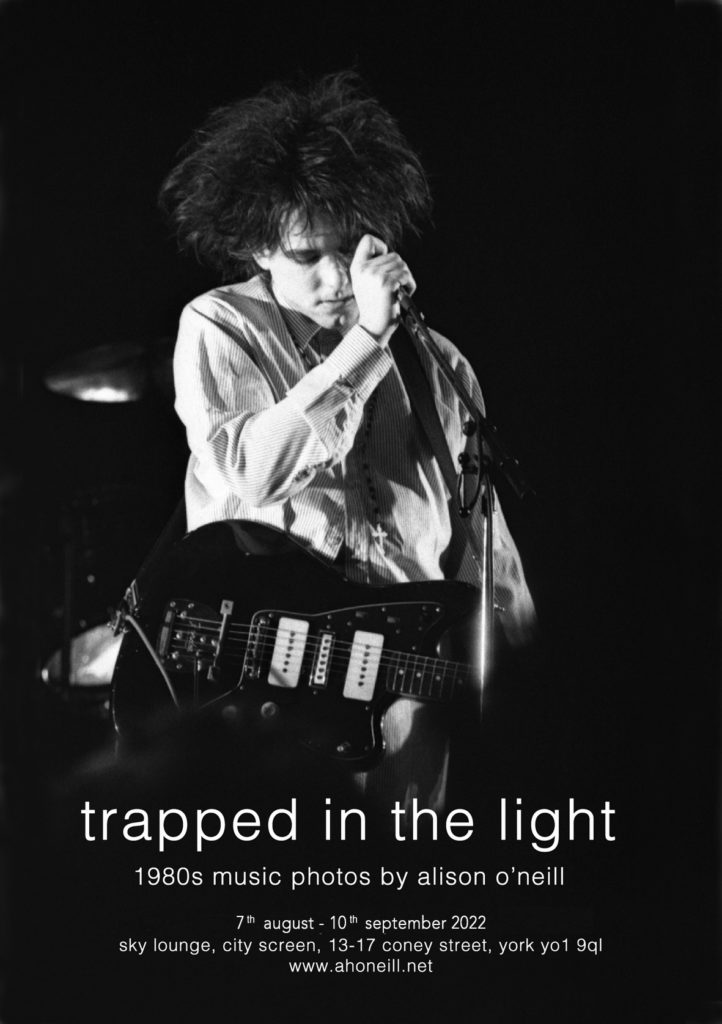

ALISON O’Neill has never exhibited her photographs of 1980s’ rock musicians until now.

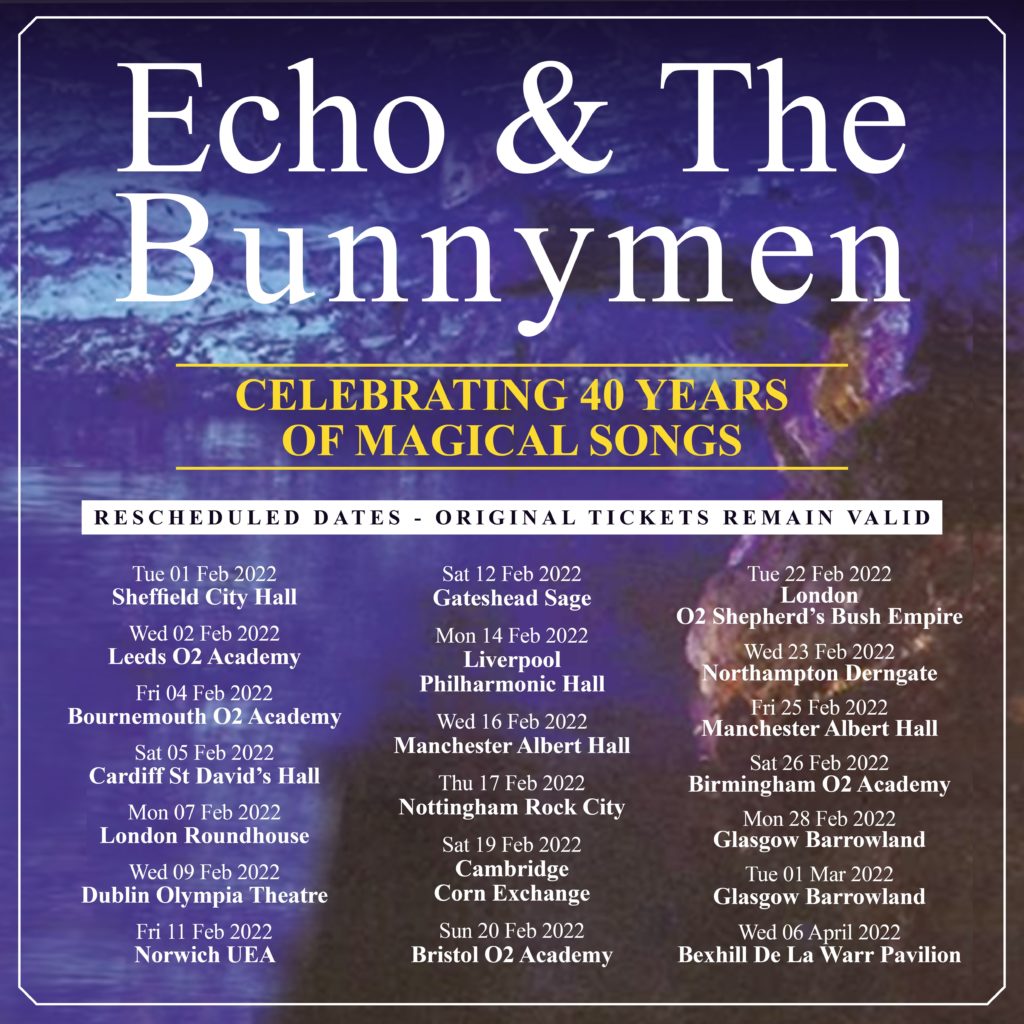

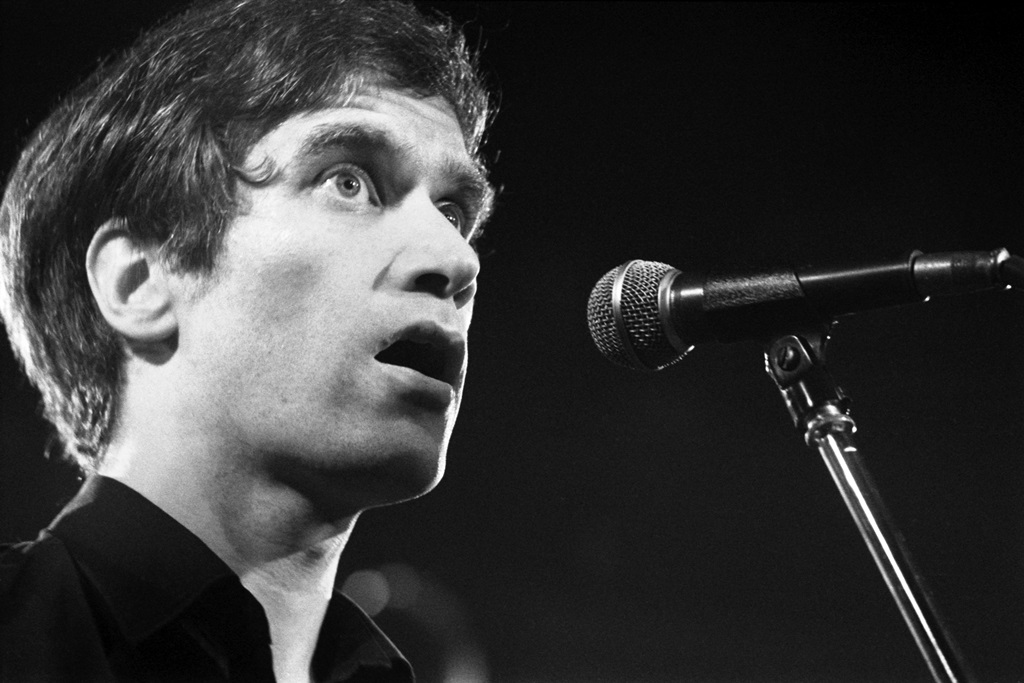

What took her so long? “Shyness,” says the North Yorkshire photographer and language services translator, whose Trapped In The Light exhibition of Robert Smith, Ian McCulloch et al is running in the Sky Lounge – the upstairs corridor – at City Screen Picturehouse, York, until September 10.

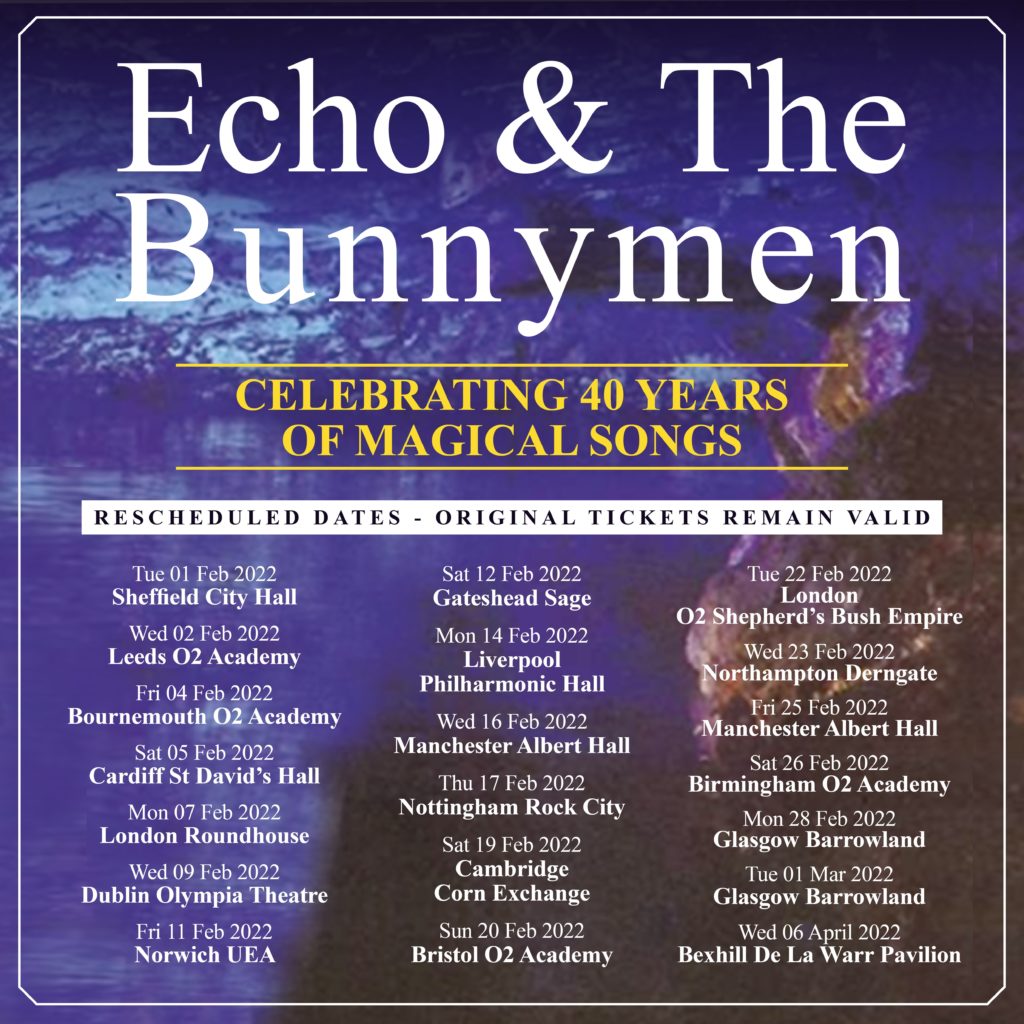

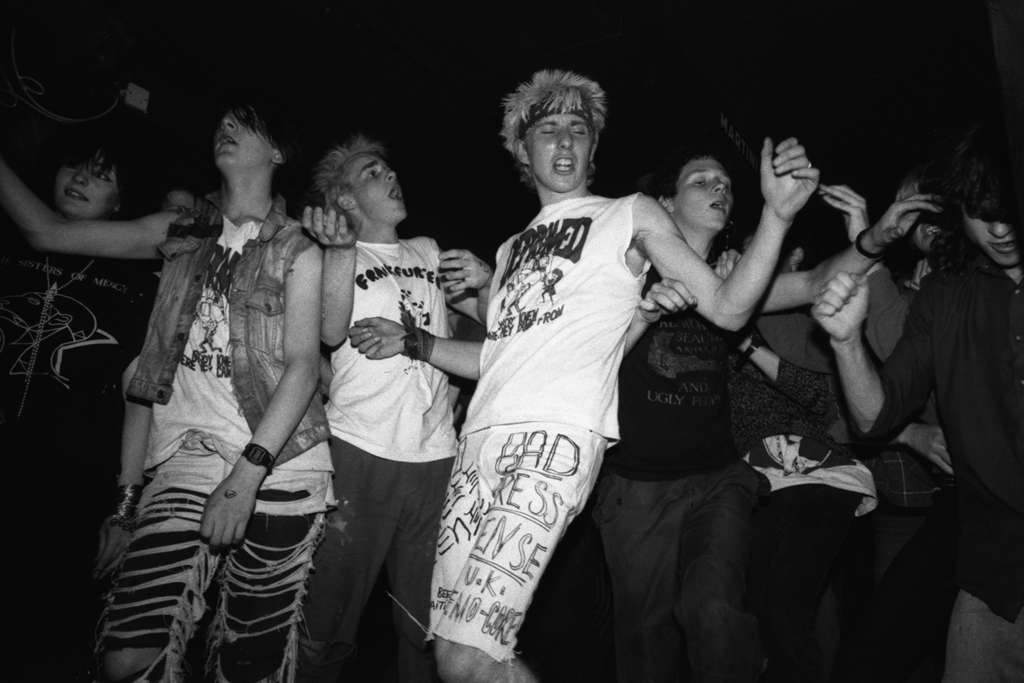

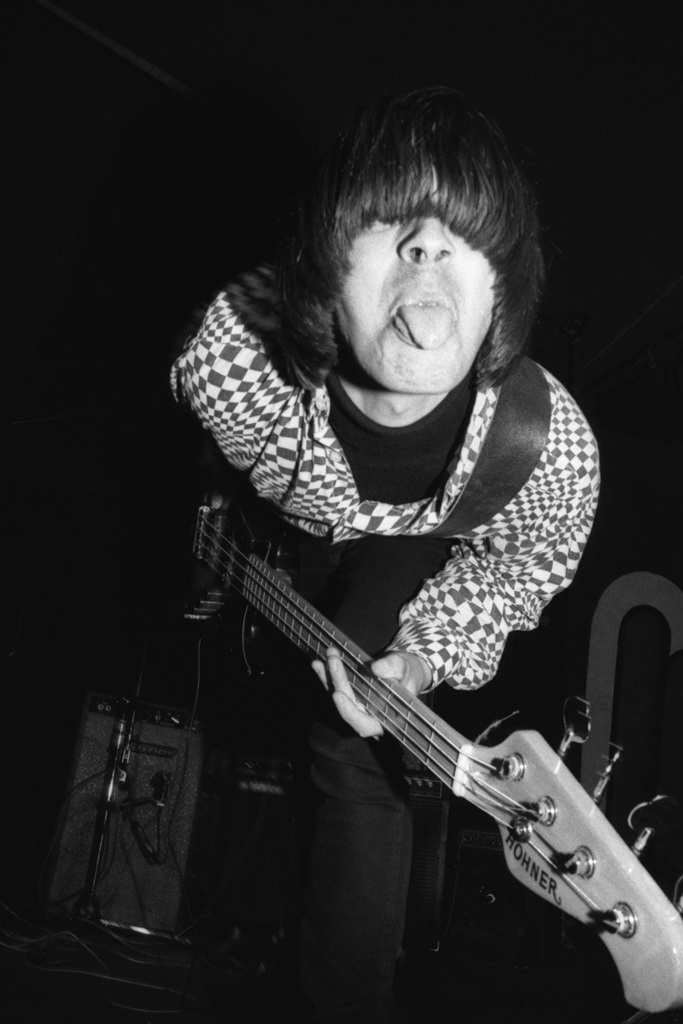

“Being in the right place at the right time takes luck and a bit of determination, and in the ’80s I had both, when I got to know The Cure and Echo & The Bunnymen,” she says. “The opportunity this gave me yielded photos that show a fan’s eye view of bands both on and off stage.”

After studying Film & Literature at Warwick University, Alison moved to Berlin for a few years and then back to Yorkshire, where she became a freelance translator of German and Dutch into English.

Her black-and-white photographs remained filed away since those Eighties’ days, most seen only by Alison’s friends, until the drive to exhibit them was finally sparked by attending exhibitions by a friend in Berlin and rock photographer Richard Bellia in London.

On show at last – the exhibition was delayed by the pandemic – are photos taken between early 1982 and 1989 at locations from London to Edinburgh, featuring The Cure, Echo & The Bunnymen, The Jesus & Mary Chain, The Cramps, Wilko Johnson, Alan Vega and local bands.

“If you want a link between them, I think all the acts bar the Hastings band – seen on a weekend away – featured on John Peel’s Radio One show. But that’s as strong a link as it gets,” says Alison.

Here CharlesHutchPress puts photographer Alison O’Neill in focus in a question-and-answer session about Trapped In The Light.

What is your connection with Yorkshire? Were you born here?

“I can’t claim to be a Yorkshire native, because I was born down south (oh, the shame!).

“But I was brought up in Yorkshire from an early age, Hull, then Pickering, so I have many friends here and my mother was still in the region, so I came back here after years away in the Midlands and Germany.”

How come the exhibition is at City Screen?

“When I asked around, City Screen were the first people to say yes to an exhibition – and it’s a brilliant space. Originally it was due to happen in May 2020 [before Covid intervened], and so the last two years’ wait has been worse than the 30-plus before.”

When did you start taking photographs and what was your first camera?

“I got an Instamatic when I was eight. By the time I was 19, I seriously needed a better one, because the old camera wasn’t up to it.”

Why rock photography?

“I fell in love with music in my teens. And when I started photographing musicians, I realised that as they were engrossed in what they were doing, they aren’t (usually) self-conscious about photos being taken.”

Were you subjected to the long-standing “First three numbers and No flash” rule for concert photographers?

“Not in relation to the pictures in this exhibition. I was an amateur photographer, so often I couldn’t get my camera in at all, but in some cases the bands gave me passes, other times the venue wasn’t as strict. I didn’t use flash much anyway.”

How did you get to know The Cure and Echo & The Bunnymen?

“Long stories! But I will say it was a lot easier to meet bands in those days. And they were very friendly and open and generous with passes. The Cure, in particular, often hung around after the show to sign stuff for anyone who wanted, so you could get to talk to them then.”

What drew you to those bands: the hair, the coats, the lips, the lipstick, the darkness…the music?!

“The emotion. The passion.”

Were you ever a Goth?

“No, I was a Cure fan! But there was a time when the way The Cure fans dressed was like a prototype for Goths.”

Which is your favourite 1980s’ album by The Cure and why? Likewise, Echo & The Bunnymen?

“I can’t do these! Years ago, I decided that I’d have to have Desert Island Bands, because I can’t choose between their albums.”

How did you gain access to photograph bands, both on stage and particularly off-stage?

“I’d ask, if I caught them going in. And once they knew me – and presumably I didn’t upset anyone – they were willing to let me hang around.”

Was your rock photography a hobby or were your works printed at the time in publications/magazines/fanzines?

“It was a hobby, although I would have liked to have worked professionally, but I lacked the confidence to sell my work. A few of my pictures have been used in the local press (Leamington), fanzines and once in a CD booklet for Nikki Sudden’s Groove (not one that’s in this exhibition).”

You say: “Being in the right place at the right time takes luck and a bit of determination”. Discuss…

“Well, I’ve sneaked in back doors at venues in my time, and bluffed security guards. At a venue in Prague where I expected to be on the guest list (but wasn’t, at least they didn’t find my name), I talked to a doorman in English – which he clearly didn’t understand – for so long that he just took my arm and pulled me inside.”

Was it more difficult, being a female photographer?

“It certainly was to be taken seriously. I imagine it still is. I could dine well on the number of people, including friends, who, learning about my music fandom go ‘oh, so you’re a groupie’. Cue Paddington death stare.”

Did you photograph any bands in York in the 1980s? If so, who, where and when?

“I did get to see TX82 – the last embodiment of Teardrop Explodes – at York Uni, but it was seated and I was near the back so I didn’t get anything good.”

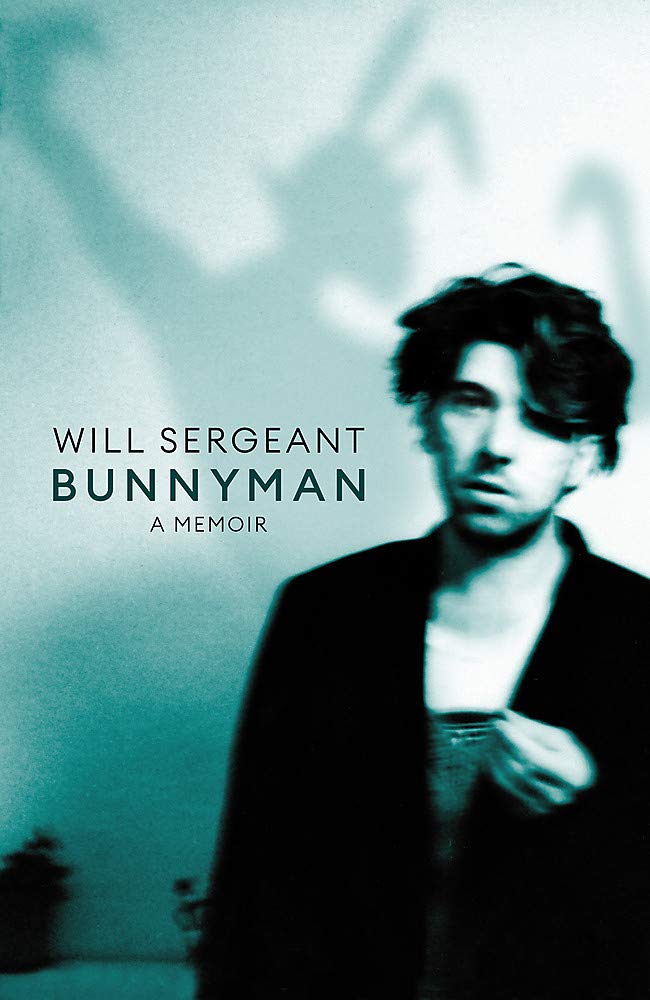

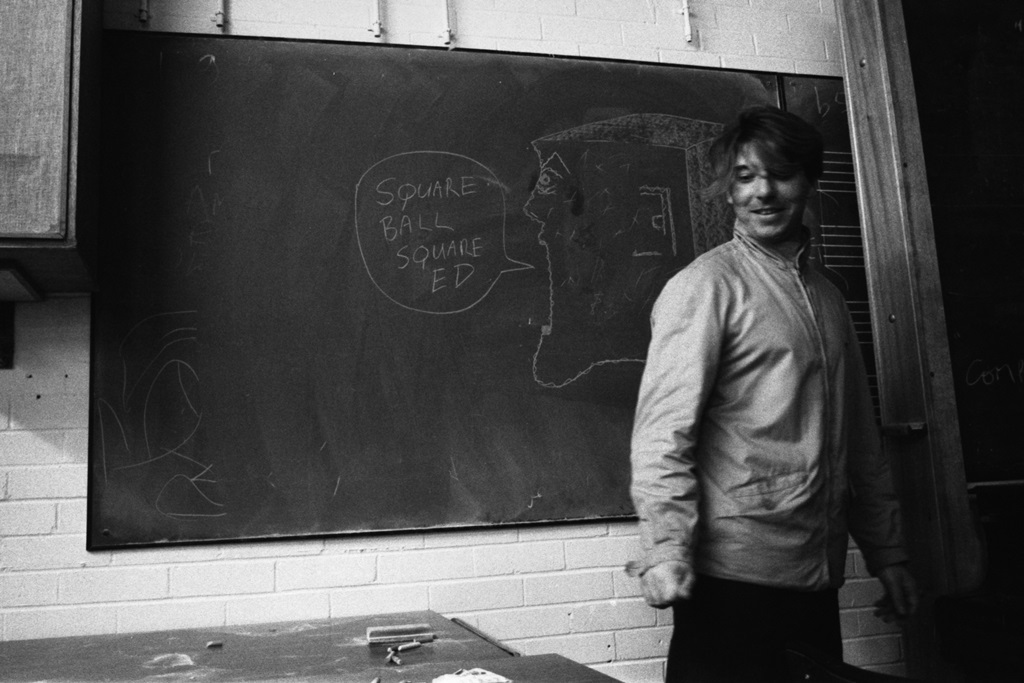

Do you have a favourite among your photos?

“It’s a close thing between Robert Smith in profile seated backstage and Will Sergeant having just drawn a cartoon on a blackboard backstage.”

Why focus on black-and-white photography in this exhibition?

“Simply to give coherence to the selection. Likewise keeping it to a set period.”

When you look back at your work from the 1980s with a 2020s’ eye, what strikes you about your work?

“How lucky I was with the timing. So many exciting artists working in wildly differing styles, and the openness to outsiders (such as me) coming along.”

What makes a good rock photographer and who is your favourite?

“I think you need a lot of patience. Anton Corbijn is my absolute favourite, but I’m lucky to have a print by Richard Bellia. I was a real photographer nerd back in the glory days of the NME and Melody Make, so I could list several more…”

Might you look to produce an accompanying book?

“I have put together a small photo book as a memento under the same title, Trapped In The Light. It’s my first try, so I’ve been waiting with bated breath to see how it’s worked out.

“My copy has arrived in time for the exhibition opening, which is rather impressive, given I only ordered it last Sunday.

“I can see a few things that need tweaking if I were to offer it for sale. The printer has a sale on, so for orders placed by August 14,I’ll be asking £34.95 plus postage and packaging. After that, the price would depend on what offers are available.”

Final question, Alison. Do you still take photographs? If so, what do you now photograph and with what camera?

“I still have a film camera, but I don’t take it out that often. I did photograph The Murder Capital when they played The Crescent, but that was in 2019. And like everyone I use my mobile for shots of varying quality.”

Trapped In The Light, 1980s Music Photos by Alison O’Neill, runs at Sky Lounge, City Screen Picturehouse, Coney Street, York, August 7 to September 10. Admission is free, open daily. Limited-edition framed prints can be ordered at £195 to £395, depending on size.

Check out Alison’s website at www.ahoneill.net

Did you know?

THE exhibition title Trapped In The Light – an apt description of the photographer’s art – is taken from the lyrics to The Cure’s song M.