NEWCASTLE. Shopping for vintage clothes. Nights on the toon. Bamburgh Beach. Camping out. Beach parties. Cheap supermarket plonk. Best friends for life. First tingle of love.

Such is the teenage stuff of David Almond’s novel for young readers, and the stuff too of Pilot Theatre artistic director Esther Richardson’s days of growing up in the North East. Been there, done that, bought the book, the first one she read after taking up her post with the York company.

Eight years later, Richardson is directing Pilot’s touring co-production in partnership with York Theatre Royal and Northern Stage, in Newcastle, where rehearsals and the first peformances took place.

Almond has adapted past works for the stage, but this time Pilot commissioned Zoe Cooper, a playwright and dramaturg who has an M Phil in playwriting from the University of Birmingham and cut her teeth on the Royal Court Young Writers programme. Both her script and Almond’s book are on sale alongside the brownies and chai lattes at the café counter.

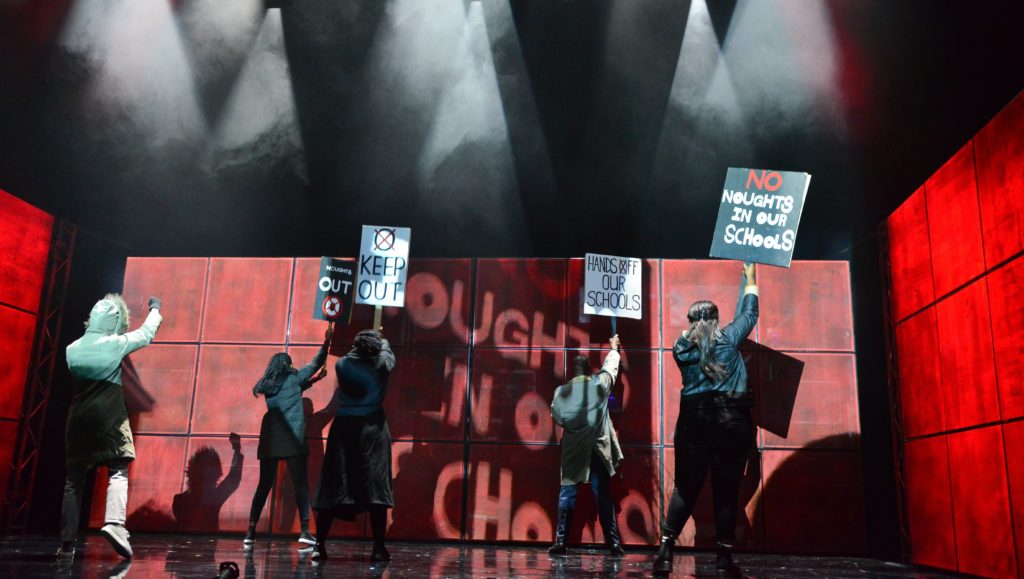

Working in tandem, Richardson and Cooper have pitched this particular theatrical tent on the cornerstones of storytelling, music, sound and vision to seek to capture the elusive nature of Orpheus, the “man-god” (as Richardson calls him). I say ‘him’, but this Orpheus is called ‘he’, ‘she’, ‘they’, at various points, depending on who is speaking.

Pilot’s primary target audience is teenage, studying Eng Lit, maybe theatre, and indeed schoolchildren were clustered in the dress circle at Thursday’s matinee, but peppered around the stalls were Theatre Royal matinee regulars.

Overhearing one in the interval and chatting with them afterwards, they praised the performances but had reservations over the storytelling. More specifically, the clarity of what we were watching. In a nutshell, not only was Orpheus elusive, so too was the story.

Your reviewer wholeheartedly agreed about the uniformly excellent cast, but did find himself drawn into the mysteries and murk of Almond’s modern-day re-telling of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, one that carried this contents notice in the foyer: References to death of a young person, bereavement/loss and adoption.

Already, on stage in York, at Stillington Mill, in Australia too, Wright & Grainger have explored the myth in a trilogy of exhilarating spoken-word and music shows, Orpheus, Eurydice and The Gods The Gods The Gods, billed as “stories from Greek mythology, told as if they were happening today”.

What Pilot Theatre’s production shares is both modernity and rich imagination in the storytelling, in this case the story of Ella Grey (Grace Long), who was adopted at the age of two and dreams of Orpheus singing to her in the company of her biological parents.

Ella prefers to spend her days and nights with Claire (Olivia Onyehara), her intense best friend since she was four, and Claire’s more open parents, with their baked aubergine suppers and ultra-comfy, tweedy sofas from a Scottish cottage industry. They understand her better, she protests.

Studying Eng Lit etc at A-level, they hook up regularly by the Northumbrian coast with Sam (Amonik Melaco), with his perfectly manicured eyebrows and far from perfect attitude towards young women; the more sensitive birdwatcher Jay (good name for a birdwatcher, Jonathan Iceton) and the ever-curious-to-experiment Angeline (Beth Crame, outstanding).

Craving a feeling of belonging, Ella is ever more drawn to Orpheus, represented here by a silhouetted figure with a crown of twigs behind white curtaining, by distant song and music too. Only she hears the voice at first, but gradually…well, that would be telling.

The content warning serves as a spoiler alert of her death, represented at the sea’s edge by her vintage dress, leaving so many questions to be answered for her friends, audience and Orpheus alike in Act Two.

Designer Verity Quinn switches the colour scheme for the two circular mounds that serve as beds and rocks on the beach from white to funereal black, accompanied by the squawk of a murder of crows and even a crow in the twig head gear worn by Claire.

All the while, Adam P McCready’s all-pervasive sound design (water, water everywhere), Chris Davey’s lighting and especially Si Cole’s video designs on the white backdrop give the atmosphere psychological depths.

Most evocative of all are the compositions of Emily Levy, whose programme note talks of her starting points of “voice (spoken and sung), folk song, and the crossover point where naturally occurring sound morphs into music”. Her songs “pass through and between the performers”, beautifully, spellbindingly so, and they evoke the mystical North East as much as The Unthanks do.

The links with the Orpheus and Eurydice of yore grow ever clearer in song and storytelling alike, as the tragedy and pain of human fallibility, the impossibility of immortality, heighten once in the underworld, but come the finale, Almond and Cooper still allow teenage dreams to be so hard to beat as new worlds beckon for Ella’s friends.

Musician Zak Younger Banks rightly joins the cast on stage to take a bow: thoroughly deserved for his vital contribution.

Performances: York Theatre Royal, tonight, 7.30pm; tomorrow, 2.30pm, 7.30pm. Box office: 01904 623568 or yorktheatreroyal.co.uk. Hull Truck Theatre, March 5 to 9, 7.30pm; 2pm Wednesday & Saturday matinees. Box office: 01482 323638 or hulltruck.co.uk.