WHERE better for internationally acclaimed artist Michaela Yearwood-Dan to spend her 30th birthday than at the launch of her commissioned contribution to National Treasures: Monet in York at York Art Gallery.

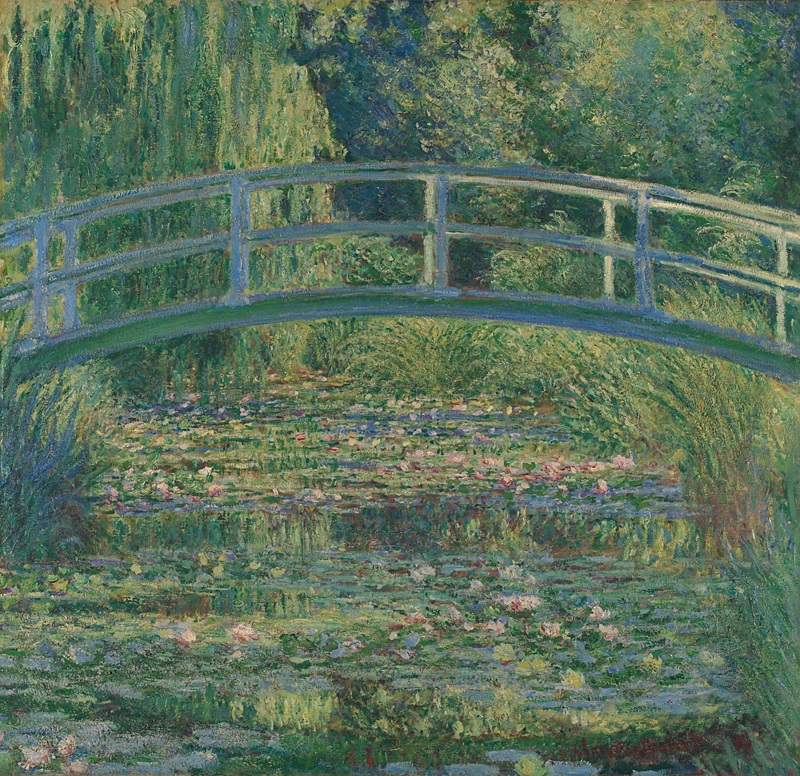

On show until September 8, Una Sinfonia is Londoner Michaela’s response to French Impressionist Claude Monet’s 1899 masterpiece The Water-Lily Pond, the centrepiece of one of 12 exhibitions nationwide to mark the National Gallery’s bicentenary – and the only one in Yorkshire.

“Being commissioned to make this new body of work in response to Monet’s legacy – and The Water-Lily Pond in particular – is a huge honour as an artist and former and forever student of painting,” said Michaela when her commission was announced.

“Having the opportunity as an artist from my varied list of demographics to be introduced into a conversation around this work of one of the world’s most historically significant European artists is an enormous milestone, and one I could not have imagined at this stage in my career.

“Taking inspiration from the way Monet formulated his bodies of work, I am very pleased with how this new series, ‘Una Sinfonia’, has turned out.”

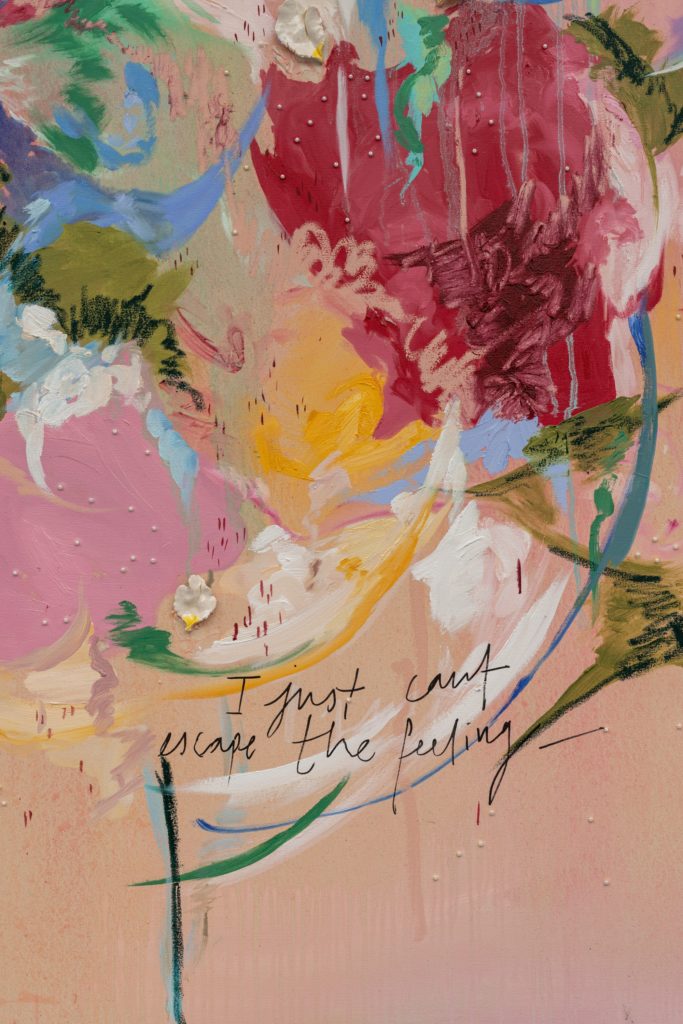

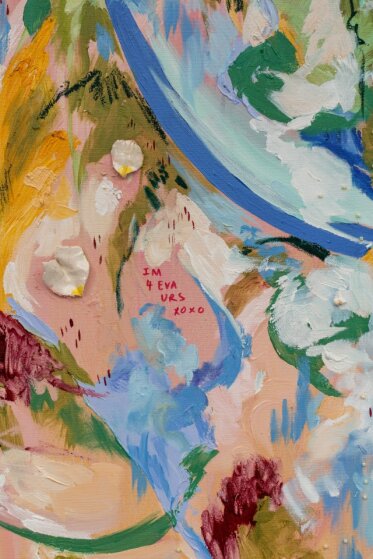

Moving freely between oils, acrylics, pastels, beads, glitter, ceramic petals, floral and botanical motifs and text, Una Sinfonia comprises nine new lush, richly textured works. Four large pieces, one for each season, are complemented by five paper works, influenced by Japanese prints, now sharing gallery space with such artists as Roy Lichtenstein and Utagawa Hiroshige, as well as Monet’s radical, influential painting from the National Gallery collection.

Explaining the Italian title of Una Sinfonia, Michaela says: “I love Italy; I don’t necessarily love Italian politics, but it’s a gorgeous place, and when I think of plein-air painting, I think of Italy.

“Two years ago, I was in Brescia for six weeks at Palazzo Monti, living in this palazzo, able to walk around the streets and go to the churches, and it was a joy.”

As the title would indicate, music was an influence too on her abstract works. “The way I work and how I work, the movement in the pieces, you can ‘see’ the musicality in that,” says Michaela.

“There are pieces of music that make me want to paint,” she adds, before recalling her musical upbringing. “At school I was in the orchestra and choir and did Saturday morning sessions till I was 15 – and then became a teenager and developed ‘teenage shame’.

“So theatre and music have always been important to me – and Italian culture lends itself to that.”

She was inspired too by Monet’s love of painting a subject in each season and his fascination with the changing quality of light in those seasons. “I was thinking about seasons and how symphonies are split into sections, and then thought of the music that maybe Monet would be listening to,” she says.

Michaela favours R&B, neo-soul, lo-fi, indie rock, as well as classical music. “There’s rarely a moment or situation in my studio, from the moment I walk in, when I’m not playing something, if not music, podcasts,” she says. “I tend to listen to podcasts when I’m doing more the more intimate works, like the paper works.”

Michaela, who paints in the studio from her photographic studies in the open air, has always loved flowers. “My mum [who lives in Leeds] has a folder from when I was a child, when I used to draw flowers a lot. It’s the physical form I love,” she says.

“But when you go into the art education system, you’re told to abandon simple things, but there’s something nice about using something simple. Flowers are beautiful to look at; they represent life, a short life span; they represent mortality.

“They have political connotations too: we wear flowers to remember fallen soldiers and to recall conflicts. So flowers have always felt an interesting subject matter.”

Consequently, Michaela’s “visual language” draws on such influences as Blackness, queerness, femininity, healing rituals and carnival culture (from childhood days in both London and Chapeltown, Leeds).

Recalling the early works of David Hockney, verbal language is important to Michaela’s works too, not only in the titles but also the use of phrases in several paintings and even messages on notepaper.

“I grew up with a dad who always took notes in a notebook,” she says. “The mobile phone has been a great development in technology, so if I have an interesting conversation or hear lyrics I like, I can write things down.

“The text I use in my paintings is always revealing or concealing because my works have a diaristic element.”

Michaela’s preference is for the viewer to “take in the movement, the colours, first, and only then look at the title and the text and take it all in”. A case in point is one of the paper works. Its title? Be My Protector. That sets you thinking, but even more so when you read the wording down the left-hand side: “It’s Too Hard To Think About What Happened”. Twice over, the response changes beyond reaction to shape, texture and colour. “It annoys me when many artists leave large works untitled,” she says.

“I like art to ask questions, for a work to have a conversation with itself, to ask a question, answer a question, ask another question. It’s nice for people to say, ‘I like this painting, and this is the reason’, but it’s always good to be questioning.”

Michaela, who names spring and autumn as her favourite seasons, reflects on what first drew her to Monet’s joy in nature. “His paintings clearly have a positive feeling, which is my favourite feeling that people get from a painting,” she says. Bang on the Monet, Michaela.

National Treasures: Monet in York – The Water-Lily Pond, in full bloom at York Art Gallery until September 8. Opening hours: Wednesday to Sunday, 10am to 5pm.