ON the portentous Friday the 13th, apocalyptic artist John Ledger will launch the preview of his Back To Normalism exhibition of drawings at Micklegate Social, Micklegate, York.

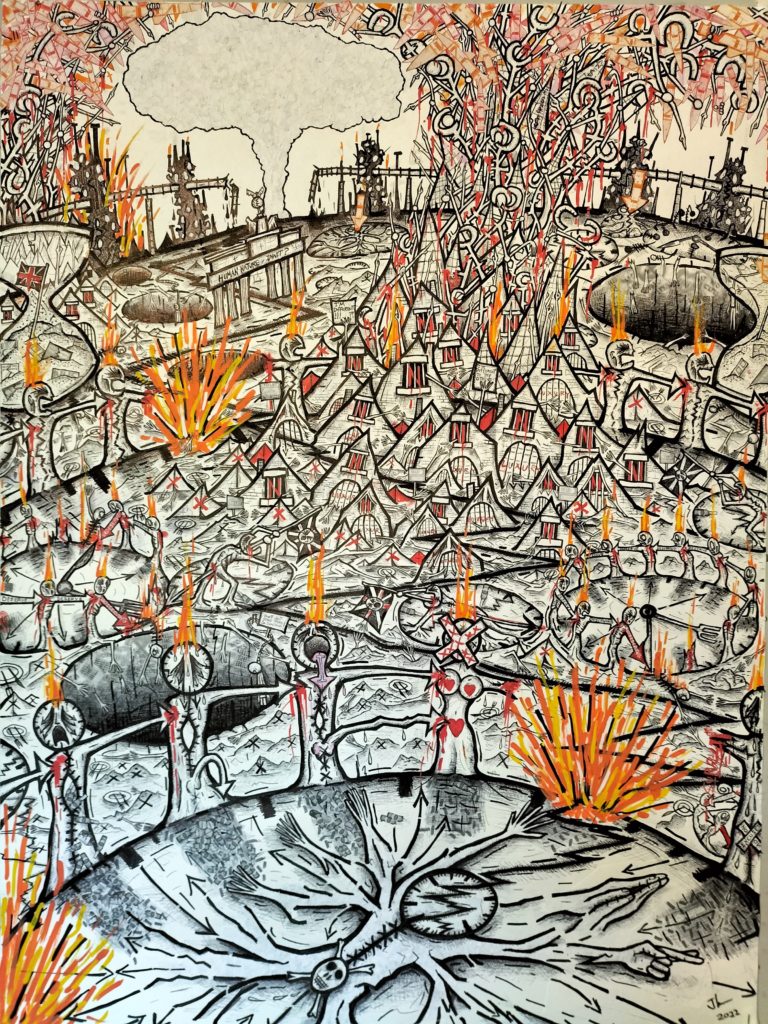

This solo show by the Barnsley provocateur addresses the theme of a time and culture that has been uprooted and disjointed by a series of crises and disasters, together with the distorting consequences of trying repeatedly to return to a “before” moment.

His latest works have come in response to Covid times, prompted by the saying “back to normal” becoming a rallying cry since the start of the pandemic as people craved a return to a life they recognised.

Exhibition curator Mike Stubbs says: “Back To Normalism looks at the uncanny reality that has unfolded ever since, and the underlying weirdness of trying to patch up the black holes in our collective experience of time.”

On show at both Micklegate Social and Fossgate Social from next Friday to March 13, the exhibition assembles a collection of the South Yorkshireman’s works that spans the past 14 years, stretching back to the 2008 financial crisis, in order to explore Ledger’s depiction of a culture that “feels increasingly stuck and detached from itself”.

“Back To Normalism explores the darkest concerns of our age, while inviting all viewers to contemplate how they felt as the world momentarily stopped in 2020, and to ask beyond the hustle and white noise of the present tense, what sort of world do you truthfully desire?” says Mike.

“The exhibition looks at a bigger picture: that since that Covid moment we have been lacking a unifying narrative that reflects the needs of the times and are trapped by the whims of defunct ideas.

“This stasis, on top of the pandemic, holds us powerless against an ongoing spate of crises, to which the default cultural cry of getting ´back to normal´ has begun to sound more warped.”

Ahead of his time as it now turns out, in 2012 Ledger participated in Pandemic York, a situationist art event that took place in the basement of Micklegate Social when it was operating as Bar Lane Studios, a community hub that provided studio space for York artists, as well as a gallery, pop-up shop, café and basement performance space.

Now named “the Den”, the basement has been presenting creative work since the end of the pandemic lockdowns. “This exhibition is the most ambitious yet, spanning both Micklegate and Fossgate Social venues and continuing to support emerging talent under the banner of Fotografic,” says Mike.

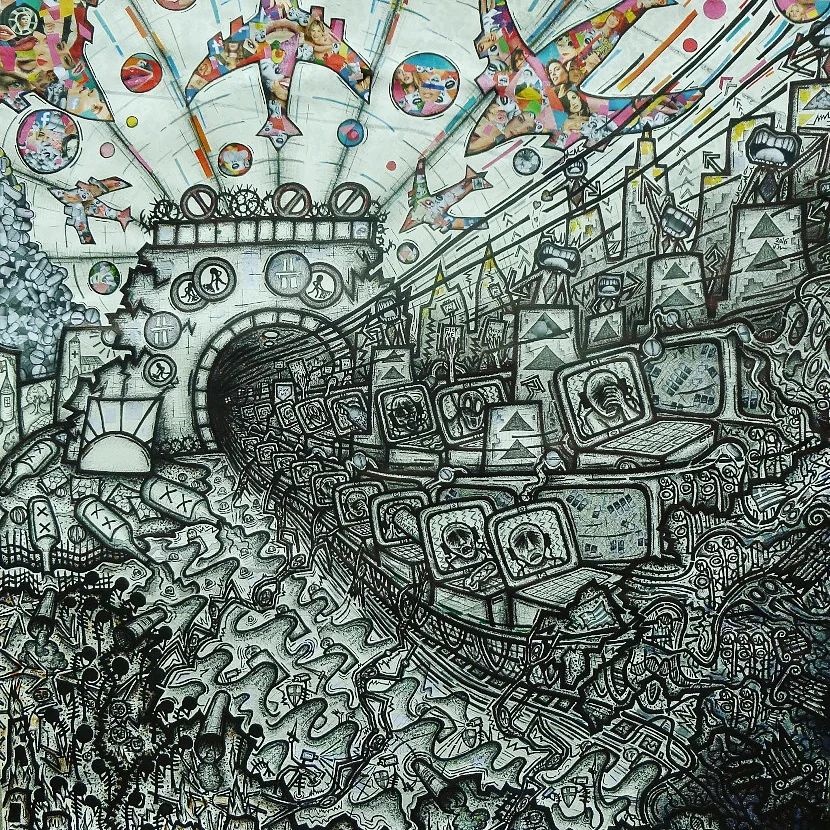

“John Ledger is an extraordinary artist who combines writing, montage, painting and drawing to create complex patterned works that comment on the most pressing issues of our time, most recently at Bloc Projects in Sheffield.

“For more than a decade, John has explored the interplay between politics, technology, addiction and mental health in contemporary society through his large-scale, chaotic-yet-meticulous drawings. We can’t wait for Back To Normalism to open.”

John Ledger back story

BORN in Barnsley, South Yorkshire in 1984, visual artist John’s work emerges from “lengthy autoethnographic and socio-political assessments”. Taking the form of large-scale drawings, maps or films, his practice is deeply informed by the post-industrial landscape and the post-historical culture that defined his formative years.

His work also looks at our relations to the “self” in late capitalism and an age of social media overload.

Since 2019, he has come to be acquainted with curator, director and filmmaker Mike Stubbs, creative producer at Doncaster Creates, and partner Sarah Lakin, from the Fossgate and Micklegate Social café bars in York, partaking in events for Artbomb in Doncaster.

John works with adults with learning disabilities in Sheffield and Rotherham, his job combining creative workshops with social day care. “The organising seeks to develop the confidence in social skills of those who attend through art and creative projects,” he says.

John Ledger discusses York’s first topical exhibition of the new year with CharlesHutchPress

How did this exhibition come about, John? Through Mike Stubbs?

“Yes, I was invited to exhibit at the The New Fringe space in Doncaster exactly three years ago. I met Mike around that point, as he was and still is very central to the Doncaster art scene, and after the Doncaster show he invited me to exhibit at the Micklegate Social.

“This was just before the pandemic, so the exhibition has had more or less had three years to develop into what is has become.”

You exhibited previously at this location in its Bar Lane Studios days in 2012. What do you recall of that show?

“It was for an inclusive, participatory event called Pandemic York: a sequel to another event held in Sheffield in 2011, right at the time of the Occupy movement that spread to cities like Sheffield.

“So, it was about art, politics and philosophy, but also about people having a good time, as it was trying to be a kind of ‘safe space’, although I’d never heard the term ‘safe space’ at that point.

“It’s a very, very hard event to locate on the internet now, though, because unfortunately the word ‘pandemic’ has a very different tone to it than it did ten years ago.”

How does the “post-industrial landscape” of Barnsley influence your work?

“That’s an interesting one. The pits had more or less gone by the time I was old enough to remember. I recall watching the Woolley Colliery be demolished with dynamite exactly 30 years ago; the area was like the surface of Mars until they built a housing estate on it.

“But this itself wasn’t a direct influence. It’s the complex social legacy that has influenced my work. The area I grew up in was next to the motorway and greenbelt, so it’s slowly become a commuter area, and dare I say, ‘middle class’.

“This has created a lot of complex feelings, as for me (and I have to be careful how I word this, because we Barnsley people are very protective over our town, which is understandable), there’s still a lot of pain here, but most noticeably in the town centre.

“I feel that I’ve been affected by it, and it’s certainly influenced my work, but the specific part of the town I am from has lost its past a little more easily – and that sometimes troubles me.

“This specific area backs onto the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. I worked there in a front-of-house position for some years. Many visitors from further afield were perplexed when you told them the town in the horizon was Barnsley; they had an almost Dante-esque mental picture of the town, and were in disbelief by the reality, of how green it looks. But behind the greenery, there’s still the scars of the post-industrial legacy.”

How did the “post-industrial culture” define your formative years?

“It did define them, but perhaps not in the expected way. As I was born in 1984, I came of age in the ’90s. As I child, the ’80s felt like this darkly lit, foreboding place, which you didn’t want to go back to.

“Partly down to improved family circumstances, the “newness” of the ’90s, the shopping centres, retail parks, made it feel like the future was going to a blissful place. At this age, I was glad the pits had gone, because it meant I didn’t have to go down them, and the culture of that time was telling me I could now be anything I want to be. The shackles of the past had been taken away.

“My thoughts and feelings on all of these things are vastly different now, but these feelings shaped a very important part of my life.

“But I was also a very sensitive child, and looking back on some of more unpleasant aspects of my childhood, such as bullying, or just the look and feel of some of the areas, it was a confused time. A lot of families were clearly damaged and dysfunctional from the breakdown of the previous work/life systems (the kind of families that largely can’t afford to live in this specific area anymore).

“It’s hard to separate these aspects as specific to towns like Barnsley, and aspects of growing up anywhere, but I’m certain there was residual trauma in these villages.”

What are “lengthy autoethnographic and socio-political assessments” and how do you turn them into artworks?

“’Autoethnographic’ is a posh word, ha-ha, that I was encouraged to use at university because I found it next to impossible to write my dissertation and make work that wasn’t deeply involved with my own experiences and present struggles. It basically means writing as a social group/community, but one that you are also part of.

“My work is this as much as my own attempts to try to visually diagnose where we are, politically and socially. I’m trying to say, ‘this is how I see our world at the moment, but this is also me, my life, my struggles, at the moment’.”

What draws you to creating large-scale works? The bigger the artwork, the bigger the impact?

“Feelings of being overwhelmed. That I often feel small, and powerless. The rings that ripple around you as an individual right up to the global. I can rarely find ways of expressing this in smaller works.”

How do you use maps in your work and why?

“I’ve always loved maps. Particularly maps of human geography. Cities, etc. But in the past ten years, maps and methods of mapping have become part of my practice.

“This exhibition will feature some elements of this ten-year process of mapping, but after ten years I only just about feel like my mapping is working artistically. It’s taken a long time to make it visually work alongside my drawing/paintings. Although some people may say that the drawings/painting are a form of mapping in themselves.”

How do you use film in your work and why?

“I’ve only come to use film in the past five years. I’ve found film a much more accessible medium when it comes to making work more explicitly about psychological/emotional battles.

“I fell out of love with drawing for a few years because it felt that the drawings were being too overtly read as political statements and nothing else. And I felt it was creating a picture of me as this ‘cocky leftie’ that I wasn’t.

“I’m quite an anxious person – that’s an understatement – and I’m not emotionally equipped for self-assured political posturing. I could never get ‘into’ politics in that boxing ring kind of way.

“Equally, I don’t judge others for their life choices (unless I feel under threat from them); most people (with obvious exceptions) are where they are because that’s what’s worked best for them in their own journey through life – and I don’t want people to feel that I’m saying ‘you’re wrong/bad’ etc.

“I make the artwork I do because it’s necessary on an emotional and existential level. For a few years, these dilemmas became very intense, and film was the best medium with which to express this.”

What is your “relation to the ‘self’ in our age of late-capitalism and social media overload”?

“As I child in the ’90s, the culture was beaming a message at us from all directions. Whether through ‘education, education, education!’ or Oasis lyrics, we were being told to ‘be yourself’.

“This equipped us to think in an individualistic manner but didn’t prepare us for how difficult it is to be authentic to yourself – how long it takes to work on yourself. A lot of the time it was just a phrase used to sell us things.

“Fast forward 25 years, and a mental health crisis is now seen as a normal thing. People are clearly so desperate to find themselves, and this is amplified as a message through social media. And it’s an intensifying feedback loop.

“I’ve found one of the most painful experiences of adult life is trying to find a self that can find its place in a world that is defined by having to ‘be something’, because being something, and being things, is crucial to finding work, finding where we’d like to live, and even things like dating.

“I felt a lot of shame in my 30s, as my friends ‘became’ things – careers and husbands, fathers etc – and I just couldn’t locate a self within our cultural constellation that I could become.

“A lot of expressed ‘negativity’ in my art is from an existential position of having not known how to be a self in the world; a lot of it has been a two fingers up to a world where I felt the pressure to ‘become’ but couldn’t find a way to do so. So, yes, my work is very deeply about selfhood in our current kind of society.”

Can you use social media in a good way?

“I use it a lot. Maybe slightly addicted. But, in all honesty, I don’t have a conclusive answer to that. It’s now so ingrained that it’s hard to imagine a reality without it. Would I like a reality without it? Maybe, I do sort of miss the days of blogging and buying newspapers. But yeah, I don’t have a confident answer on the matter.”

Are we in an even worse place than we were in 2008. when mired in a financial meltdown, and how does your work over the past 14 year reflect that?

“I’ve often been accused (or at least felt accused) of presenting an image of ‘reality’ that is actually just in my head. But any outlook of reality is going to be coloured by how the person presenting it is feeling, and those feelings are informed by concrete factors of reality.

“This question, at root, goes back to the time-immemorial debate about whether we ourselves control our destiny or whether external forces control it. I hope it’s evident that this has been an ongoing focus of concern in the work I make.

“I feel like I needed to go there, before answering if I think January 2023 is worse than January 2008. There’s a work in this show from 2008, quite an important one. It very much belongs to the same family of landscape drawings I have been making ever since, yet from around 2013 onwards, my work began to get even darker.

“I’ve experienced the past ten years as a decade of increasingly heavy energy, although there have been moments of surprise that have momentarily brought different energies in.

“I would say that we, as a society in 2023, are in a dark place, although I’m not without hope in the knowledge that things can change unexpectedly. But are these my own feelings? Do they reflect only me, and how I feel, or is it a sense of reality shared by many? I think the only way to properly answer this is by asking the people who look at and engage with the work I make.”

How does “a culture become stuck and detached from itself”?

“That’s a hard one to answer in a rush. I’ll try to identify a few symptoms and see if they correlate with the statement I made!

“Number one: I find increasing amounts of people, young and old, feel like time no longer moves with the same rhythm and continuity that it possibly did in, say, 2008, when we weren’t as dependent on social media and smart phones (although they were there, they were still partly novelty).

“In public space, I often feel haunted by music that still seems to be being played as if it is contemporary, but it’s not, it’s actually like 15 years old or something. This is partly because new music these days doesn’t command the dominance it got through TV and radio, pre-streaming days.

“But sometimes I feel like we’re still partly stuck in the 2000s, even the 1990s, and that this could be not just down to how this newer technology has altered the experience of everyday life, but because we feel happier there, because something about those times made more sense to us.

“I think there’s a real sense that nobody can make sense of all the things that are occurring in the world these days, and that this is reflected in a culture. I have to add a disclaimer that a lot of these ideas have been informed by the late writer Mark Fisher, who wrote a non-fiction book called Ghosts Of My Life, in which he said ‘the past keeps returning because the present cannot be remembered’.

“Number two: If we could identify our age as one stuck in a state of trying to get back to a ‘normal’, some aspects of life such as increased homelessness, food banks, really happening climate change, things that would have terrified us if they just emerged in their current state 15 years ago, have become ‘normalised’.

“We have grown used to things such as new upmarket bits of town centres coexisting with folk laying on the street, on the drug spice, looking like they’re dead, or climate change like we had last summer.

“This creates a dislocation within us. Humans always compartmentalise, and can disregard inconvenience, but what I’ve seen over the past decade has really worried me.

“And, look, I’m giving this answer in a trendy cafe right now, so I’m not judging anyone for wanting to go to nice places! And there’s nothing wrong with nice places to go, dressing nice, or any of that! It’s just this dislocation that seems to have occurred; it concerns me.

“But equally, I admit I’m saying some pretty heavy stuff here, in responding to these questions. I don’t want to make people feel like they have to think all this kind of stuff to get my work! If people like the drawing for its own sake, and they enjoy the show, then that’s good…probably better than getting bogged down in all of this!”

Graduating in 2019 as a ‘mature student’, how did your MA in Fine Art at the University of Leeds influence your work? Did your work change?

“I really enjoyed being back in a university environment and having that freedom again. It wasn’t all plain sailing; for a start, I encountered a lot of imposter syndrome, being around young, confident well-spoken students, because, as much as I know, in such esteemed environments, I felt intellectually clumsy with my flat-toned Yorkshire accent.

“And I started around the months of the #metoo moment (which, I’d argue, alongside Black Lives Matter have been some of the most important events of the past ten years). This, and the fact that culture is now very much invested in breaking down a more historically, white, male, heteronormative slant on the world, gave me a lot of deep self-reflection – some of it, admittedly, pretty unpleasant.

“But I think this is what made me, and my work, change during my Masters. I intellectually agreed with all the social justice stuff, but I needed to unpack why it was producing very pleasant feelings, while trying to understand why the university environment was giving me imposter syndrome, and it gave life to the film work I mentioned earlier.

“Film work allowed me to look at issues such as toxic masculinity, from a ‘lived in’ perspective, but certainly one that wasn’t endorsing these things, but looking at it as a social problem that leads to dangerous things like ‘incel’ culture.

“I created a fictionalised film based on personal experiences of mental health, isolation and societal expectations, but I twisted the story to talk about the black hole of radicalisation happening to lots of, specifically, men on the internet.

“This sounds all very bleak and heavy, but my time making this film at Leeds was one of the most enjoyable times of my life.”

How do you respond to the statement on a gallery poster: “Beware of artists. They mix with all classes of society and are therefore the most dangerous”?

“That’s quite difficult to answer, but I think art allows people of all social groups to sit with ideas and concepts that would probably rub more problematically against the identities and beliefs if those same thoughts were delivered in, say, a twitter post, for example.

“But, for me, art is a meeting place of many ideas; it’s rarely just saying one specific thing. And for me, that’s where its potency is. But that admittedly is more a definition of the type of work I make.”

For Ai Weiwei’s exhibition The Liberty of Doubt, at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, last year, the Chinese artist and activist made badges and mugs that said: “Everything Is Art. Everything Is Politics”. Is it?

“I think it is…and isn’t. I think just as humans are able to hold contradictory beliefs simultaneously, we’re all capable of picking and choosing what is art and what is politics at any given moment. But yeah, it doesn’t disprove the statement.”

How would you sum up the work in the Back To Normalism exhibition? Is there really such a thing as “normal”?

“I don’t think there is a ‘normal’, but there is an almost shared mental picture of ‘normal’ that holds a collective/a society together. These aren’t my words (it’s kind of half taken from writer George Monbiot), but all societies function by a story, which, even if we are personally critical of it, it creates a cohesiveness that makes a society function.

“The premise of Back To Normalism is built on this idea that the functioning story we, at least in the UK, had until 2008 was one built by the narratives of both Thatcherism and New Labour, and whether you liked it or loathed it, it created a story that enabled a social cohesion for enough of that society.

“I believe that this stopped in 2008, but we went into an age of trying to return to pre-2008, through sticking plasters, and this has been most notable since after the pandemic.

“But I believe trying to get back to a normal, when the actual present situation has so vastly changed, creates a warped reality.”

In your latest blog on January 3 at johnledger1984.wordpress.com, you say, “I realise that at near-enough 40, I’m in a place I always prayed I’d never be in”. When you turn 40 next year, what will you seek to achieve in your art and life in the decade ahead. having been “on the run” in your 30s?

“I wish to find a more sustainable and healthy confluence with both art and life.”

But does an artist need to be restless, dissatisfied, troubled?

“I hope not, for my own future’s sake!”

How do you move on when consumed by a sense of failure? Keep drawing?

“It does help sometimes. But you need friends too, and community, and sunny spring days that lift the gloom. I can easily go heavy into what my work is about, and sound like I don’t have any hope. But I do. I think if I lost all hope, I’d stop making art.”

John Ledger: Back To Normalism, on show at Micklegate and Fossgate Social, York, from January 13 to March 13. Friday’s 7pm preview will include a sonic performance by artist Adam Denton, in collaboration with John Ledger. Drinks will be served.