TWELVE artists from York collective Navigators Art are opening their mixed-media exhibition at StreetLife’s project hub in Coney Street, York, this evening (17/10/2022).

Drawing inspiration from the city’s rich heritage and vibrant creative communities, the project explores new ways to revitalise and diversify Coney Street, York’s premium shopping street but one blighted with multiple empty premises.

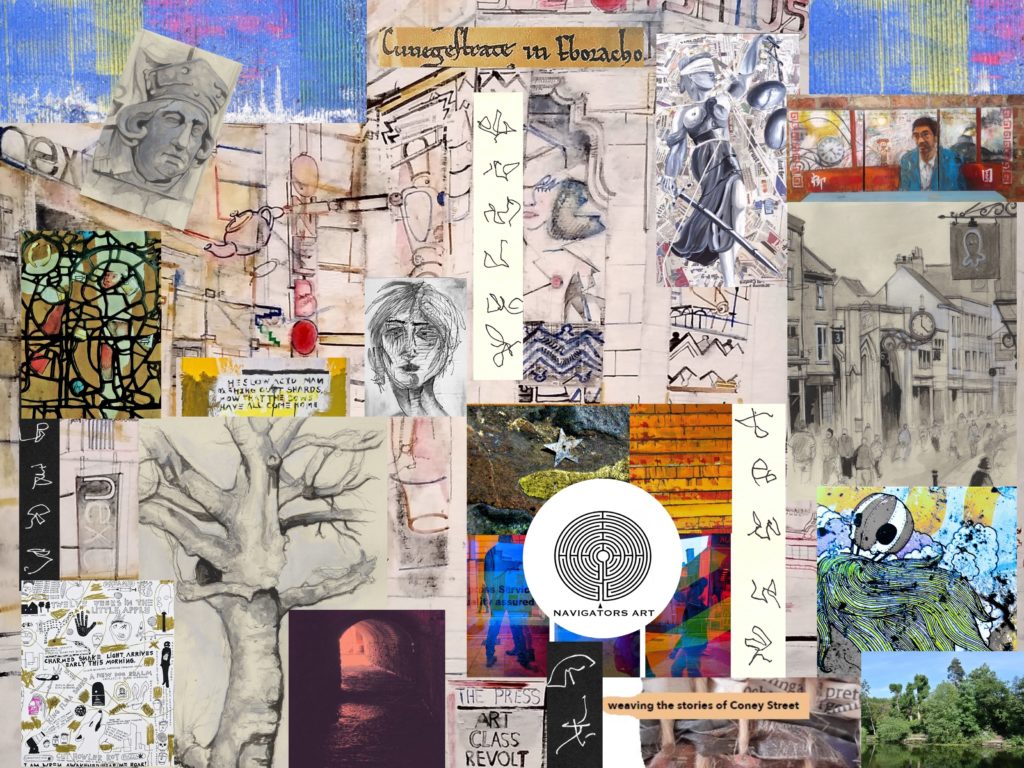

In a creative response to Coney Street’s past, present and future, Navigators Art have made new work for StreetLife, designed to enhance and interpret its research, under the title Coney St Jam: An Art Intervention.

On show from today to November 19 will be painting, drawing, collage, photography, textiles, projections, music, poetry and 3D work. Entry to the exhibition space is accessible by one set of stairs.

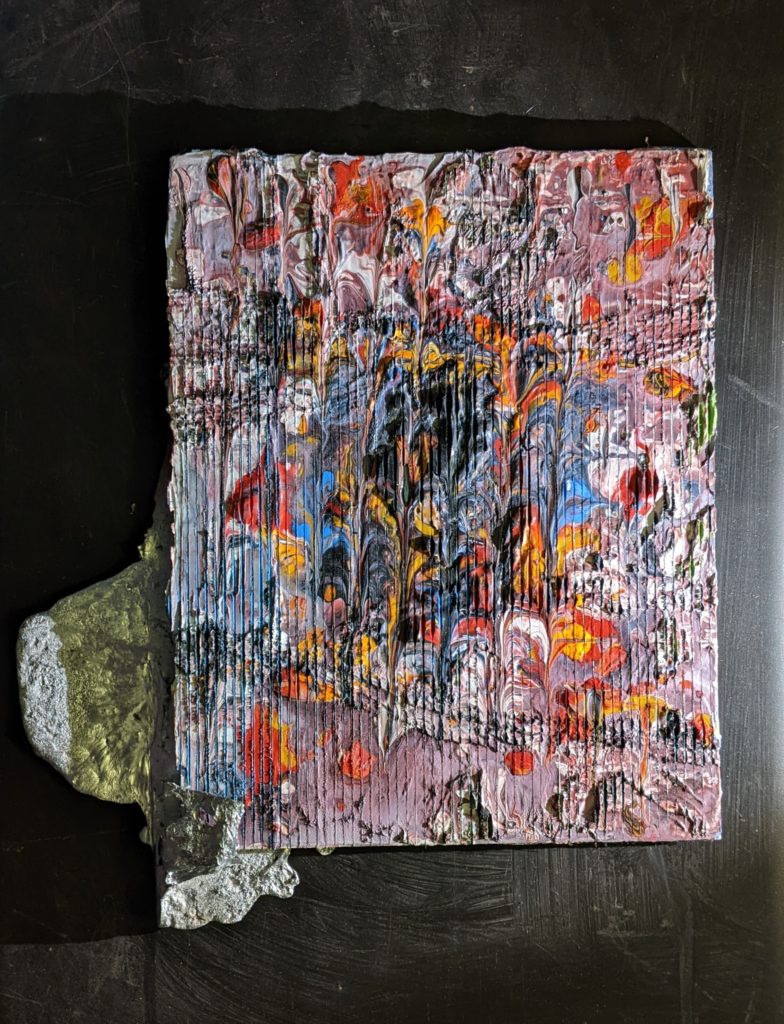

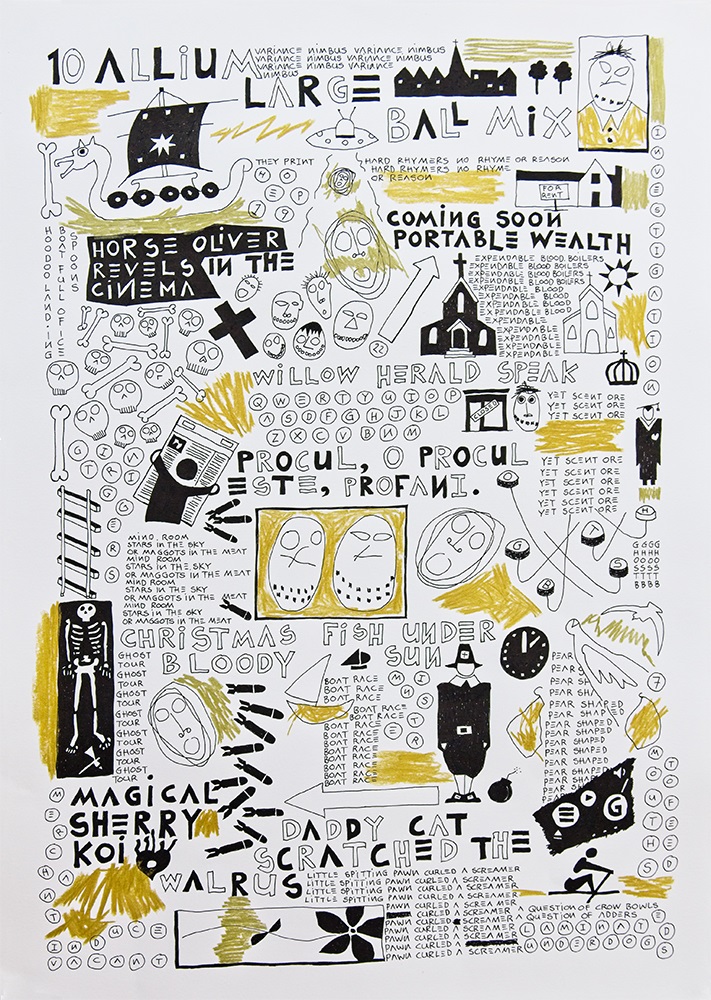

Taking part are: Steve Beadle, figurative painting and drawing; Michael Dawson, mixed-media painting; Alfie Fox, creative photography; Alan Gillott, architectural and scenic photography; Oz Hardwick, creative photography, and Richard Kitchen, collage, abstract drawing, prints and poetry.

So too are: Katie Lewis, textiles; Tim Morrison, painting and constructions; Peter Roman, figurative painting; Amy Elena Thompson, prints and tattoos; Dylan Thompson, composer, and Nick Walters, painting, video and sculpture.

Here, CharlesHutchPress puts questions to Navigators Art co-founder, artist and poet Richard Kitchen.

How did the exhibition come about?

“I heard talk of this project rather belatedly in April this year. After our Moving Pictures show at City Screen and providing art for York Theatre Royal’s Takeover Festival, I was looking for a community project the group could really get to grips with and actively support.

“I rather cheekily offered our services to the StreetLife project leaders and, after a bit of convincing, they agreed to let us devise an exhibition for them.”

What relationship have you established with StreetLife?

“A very good one. They were a bit wary at first, as we hadn’t been part of the initial set-up, but we convinced them we were genuinely interested in the project and wanted to interpret and enhance their research and findings creatively for a wider audience. That’s one of our missions as Navigators Art. This isn’t just another art exhibition!

“They’ve been really helpful with practical arrangements, allocated us a budget and agreed to let us put on an evening of live performance in aid of the homeless to mark the end of the show on November 19. That’s going to be very exciting.”

In turn, what relationship have you established with project participants University of York, City of York Council, Make It York, My City Centre, York Civic Trust, York Music Venues Network and Thin Ice Press?

“The project leaders are all from the university, so we’ve got to know them, and also Bethan [cultural development manager Bethan Gibb-Reid] at Make It York. We’re not directly involved with the other agents as such, but we’re all part of the same enterprise and hopefully we can continue to develop existing relationships and make new ones.

“Collaboration is what we’re all about, now and in the future. Making project-specific and even site-specific work has been a very positive creative challenge, from which we’ve all learnt something, and we’re looking forward to further opportunities.”

How do you foresee the future of Coney Street?

“It’s in an interesting state of flux. I can’t speak for the StreetLife project itself or even fellow artists, but personally I regret that a future seems securable only through the involvement of giant property developers.

“I wish a more grassroots solution could be sought and found. But the Helmsley Group’s plans are on show to all at the StreetLife hub in Coney Street and there are public feedback forms by way of consultation.

“It looks positive enough, with provision for new green spaces and so on; I just hope it’s not all about financial interest at the expense of those who live here, or about economics over culture and wellbeing. Naturally, I’d love to see a cheap, Bohemian cultural quarter there, but I doubt that’s top of the agenda!

“Whatever the plans, serious thought needs to be given to social issues such as the question of accessibility. If the street is to be traffic-free, it also has to be accessible to all. The present system of bollards means that some people are unable to use the street at all. That doesn’t make sense.”

How much should the past of Coney Street feed into its future?

“Its past was very much involved with the river, and future plans include developing the river area as a public space and retying lost connections between the river and the street in general. The thriving, lively street of yore is a model for what it may become again. And no future is sustainable without a foundation in history.

“The past can be celebrated and kept alive. It doesn’t have to be enshrined as a museum piece; certainly not one that people have to pay to enjoy! That’s something artists can offer.

Who should be taking the lead in envisioning the future? Looking at that list of who’s involved already, how do you establish joined-up thinking?

“That’s a question for them rather than us, I think. We’re only putting up some pictures! But all walks of life and all sectors should be having an equal say. I don’t think any of those groups is acting independently of the others. There is consultation, including with the developers.”

Where do the arts and art fit into that future?

“The arts are essential to public, cultural and personal wellbeing, despite efforts to ignore, undermine, underfund and generally devalue them to a shocking and highly unintelligent extent. The arts should be central to every decision-making process in government and to education at every level.

“In the times we’re living through, we need creative solutions on a gigantic scale and we need the sheer energy of the arts to help us survive and adapt. Those things aren’t going to be provided by bureaucracy or petty squabbling between political parties.

“I’d say give artists the kudos they deserve and let us help to turn things around. Pay us. Give us space to work in: let us use those empty buildings! Art isn’t just about old monuments. There are many living artists in York who could successfully take on social responsibilities because of the nature of what they do. We’re an asset to the city and should be valued and promoted as such.

“Make Coney Street a flagship enclave for creatives and independent small retailers and an affordable, inspiring resource for the public to enjoy. That’s something we provided when we were based at Piccadilly [Piccadilly Pop Up] and we came to realise more and more how much that environment meant to people and benefited them. Offer that on a much wider scale and we’ll see real change for the better in society.”

What else is coming up for Navigators Art? Are you any closer to finding a new home?

“From January to March next year, some of us will be exhibiting at Helmsley Arts Centre, and we’ll be at City Screen again in March and April. We may be involved with Archaeology York’s Roman dig next year too.

“We’re eager to take on future community projects and commissions. We’re all artists in our own right but collectively we’re about much more than making and selling. We want to make a difference to the city and its people.

“We’ve grown from being just Steve Beadle and myself in 2020 to a trio last spring with Tim Morrison, and now we’re 12, including writers and musicians, as well as visual artists. The group is fluid, though, and we won’t all be involved in every venture. Some will come and go, others will join.

“Many of us have jobs and families and we’ve all worked on this show voluntarily, but I think we can continue to match the size of the group to the size of the project. Clearly, we’re not going to find one home for all and that’s fine. It would be wonderful to have a studio identity but we don’t have the funds for it at the moment.

“Others are welcome to join us any time. Steve and I want to develop the other strand of Navigators Art’s mission statement, which we started at Piccadilly Pop Up last year: to mentor young and under-represented emerging artists. Not everyone at Piccadilly shared that vision but I think we’re better prepared to do it now.

“Apart from anything else, we’d like to shake things up a bit culturally for ourselves. The initial longlist for Coney St Jam artists was quite diverse, but for health-related and other reasons we’ve ended up with a bunch of mostly white males. We’re working on that!”

Coney St Jam: An Art Intervention by Navigators Art, at StreetLife Project Hub, 29-31 Coney Street, York, opening tonight, 6pm to 8pm; then 10am to 5pm, Monday to Saturday, except Wednesdays; 11am to 4pm, Sundays. Free entry.

Free tickets for tonight can be booked via https://streetlifeyork.uk/events/coney-st-jam-navigators-art-exhibition-launch-and-press-night

A live performance event on November 19, from 7pm to 10pm, will mark the end of the show.

What is StreetLife?

FUNDED by the UK Government Community Renewal Fund, StreetLife explores new ways to revitalise and diversify Coney Street, drawing inspiration from York’s history, heritage and creative communities and involving businesses, the public and other stakeholders in shaping the future of the high street.

The project is led by the University of York, in partnership with City of York Council, including Make It York/My City Centre, York Civic Trust, York Music Venues Network and creative practitioners, such as Thin Ice Press.