Late Music presents Gemini, Unitarian Chapel, St Saviourgate, York, December 3

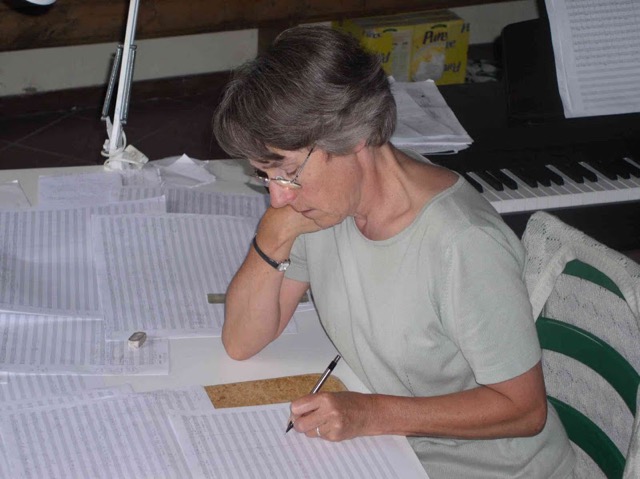

NICOLAS LeFanu’s 75th birthday earlier this year was celebrated in fine style by one of our most distinguished and long-lived groups, Gemini, itself only a year short of its half-century. Two of her own works framed eight others, including one by her husband David Lumsdaine.

Gemini is a flexible ensemble led from the clarinet by Ian Mitchell. Here he was joined by a piano trio for the premiere of LeFanu’s appropriately titled Gemini Quartet, newly commissioned and written only this summer.

As an opener it was designed to reflect how we welcome others, in a dozen or so brief “bagatelles” (her word), some of only a few seconds. It charms with surprises, moving seamlessly between comfort and anguish, impressionism and rhythm, sometimes noisy, more often gentle, using the instruments in a variety of different groupings. Gemini delivered it with loving care. I could only have wished its 13 minutes had lasted longer.

At the end of the evening, more than two hours later, we heard her Piano Trio of 2003. Its single movement is rhapsodic, all its material developed from high harmonics and tremolos, which are soon amplified by a piano solo. It charts a fascinating course between nerviness and relaxation, the two moods changing between strings and piano, as dialogue influences their responses to one another.

As always with LeFanu, her orchestration is imaginative. It eventually reaches a harmonious conclusion, with trills in the piano as the strings disappear into the ether. Gemini interacted intuitively throughout.

Only a handful of the other works on the programme reached these levels. One of them was another premiere, David Lancaster’s Hell’s Bells Bagatelles, inspired by church bells, especially those of York Minster, and conceived over the last five years.

In his words, its five sections may reflect ecstasy or doom, but within those extremes his use of rhythm verges on dance most appealingly and pizzicato cleverly and regularly evokes the percussive ping of bells.

Lumsdaine’s Blue Upon Blue (1991), for unaccompanied cello, also fell pleasingly on the ear, combining slow melody with more urgent, un-tuned ‘commentary’ from wood, gut and hair, and transitioning between the two by means of glissandos. Sophie Harris teased out its essential lyricism with focused intensity.

Thomas Adès’s suite from his 2005 opera The Tempest was predictably clear-cut in its reactions to six Shakespearean scenarios, always with an ear to vocal characteristics in the four instruments.

Space forbids discussion of the other works, most of which fell into the category of vignettes. For the record they included two pieces without piano, Dorothy Ker’s Water Mountain (1999) and Blaze And Fall (2017) by Charlotte Bray, Martin Suckling’s Three Venus Haikus (2009), setting poetry by George Bruce, and two lockdown pieces for solo piano (Aleksander Szram) by Janet Graham, Church Blackbird and Advent Thoughts. All had something positive to offer.

But most of all we were reminded just how valuable an asset Nicola LeFanu is to York, Yorkshire and well beyond. Many happy returns!

Review by Martin Dreyer