MOTHS have a bad press and basically The Bible is to blame.

Or so says mezzotint artist and moth crusader Sarah Gillespie, whose remarkable exhibition can be discovered by day at Castle Howard, near York, until September 5.

“It’s just for some reason, we are so ignorant about moths,” says Sarah, speaking during her residency at the Head Gardener’s Cottage in the walled Rose Garden.

Part of the Lepidoptera group of insects, meaning “scaly winged”, moths are “deeply unloved”, “grossly misunderstood” and dismissed as “pests”, in favour of the more colourful, daylight-dwelling butterfly, and yet moths are more numerous and more varied, as the exhibition publicity asserts.

“Moths are much more interesting than butterflies. They really are. Butterflies are so boring by comparison. Did you know, there are more diurnal flying moth species in the UK than butterflies?” says Sarah.

Er, no, but anyway, back to that bad press/fake news about The Bible’s disparaging words. Moths flutter through the pages of The Great Book on no fewer than ten occasions, but none has had such a detrimental impact on the moth’s reputation as the Gospel according to St Matthew, chapter 6, verse 19: “Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal.”

“We associate moths with making holes in wool, but not one of the 2,500 species of larger moths does that. Moths don’t eat clothes. It’s only the larvae of one species of micro moth that does it. Some adult moths don’t even have mouth parts, and those that do tend to use them just for pollinating.”

The exhibition is the result of an ongoing project that, for the past two years, has seen Devon artist Sarah research, draw and engrave common English moths by way of highlighting their dramatic and devastating decline and celebrating their overwhelming importance.

Since 1914, it is believed that around 62 species of moths have become extinct in Britain alone. In the last 35 years, the overall number of moths here has fallen by around one third owing to habitat loss, intensive farming, commercial forestry and light pollution.

“If what I have been given [through making mezzotints of moths] is the ability to focus, to pay attention, and if there is even the remotest chance that in attending lies an antidote to our careless destruction, then that’s what I have to do – to focus,” says Sarah. “It’s not enough but it’s necessary.

“It’s just for some reason, we are so ignorant about moths. We think of them of them as nocturnal, as the butterflies of the night – the French call them ‘papillon de nuit’ – but many are diurnal.

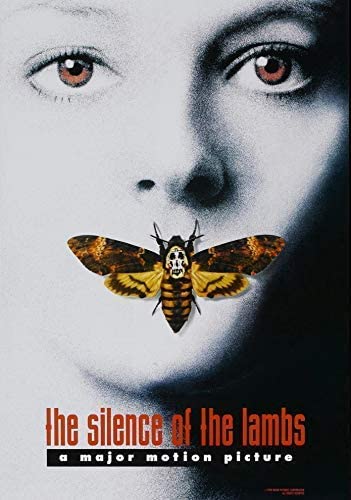

“It doesn’t help that a lot of people were spooked by the moth in the poster for The Silence Of The Lambs [Jonathan Demme’s 1991 American psychological horror movie]. It’s called the Death’s-Head Hawkmoth because it has what looks like a skull on the back of its head.

“But, in fact, the Death’s Head Hawkmoth has nothing to do with death at all. It goes into beehives to eat honey and the bees happily let it in. It’s not parasitic; it doesn’t hurt the bees; it just takes their honey! The larvae eat potato crops.”

Apart from that, what did moths ever do for us, Sarah? “They’re pollinators. They’re re-cyclers. The reason their larvae eat your cashmere jumpers is to break down animal hair. They evolved to be part of that entropy. Otherwise, we would be drowning in animal hair,” she says.

“They’re a crucial part of the food chain too. Bats eat them on the wing, but we’re seeing a drop in bat numbers over farmland because farmers use pesticides to get rid of moths.”

Anything else? “The UK’s Blue Tit population needs 35 billion moth caterpillars a year to eat. They time the hatching of their chicks for when the caterpillars are around,” Sarah highlights.

“If you wonder why we no longer hear cuckoos like we used to…cuckoos had adapted to eat the hairy caterpillars of the Tiger Moth, but Tiger Moths are down in number by 83 per cent over the past 30 years because of pesticides.

“We tend to think of moths in their adult form but they’re in a cycle and because that’s entangled with other species, they’re the canary in the coal mine in this country, being so entangled with biodiversity and ecosystems.

“The RSPB brought out a report in May that said we are the worst country in the G7 at looking after at our biodiversity. We have only 50 per cent of diversity left. Moths are a huge part of that decay, being a vital part of the food chain and pollinators – and yet we’re afraid of them.

“It’s a depressing story, and no-one wants a depressing story right now, but we do just about have time to turn it around.”

Hence Sarah’s work seeks to “draw attention to this catastrophic collapse while tenderly celebrating moths’ unseen nocturnal lives, exquisite diversity and the poetry of their common English names”.

The resulting Moth exhibition features all 22 of her mezzotints as well as a new work, her largest mezzotint to date. Measuring a monumental 2ft by 3ft, Peppered Moth marks a stark change to a process normally measured in inches and not feet.

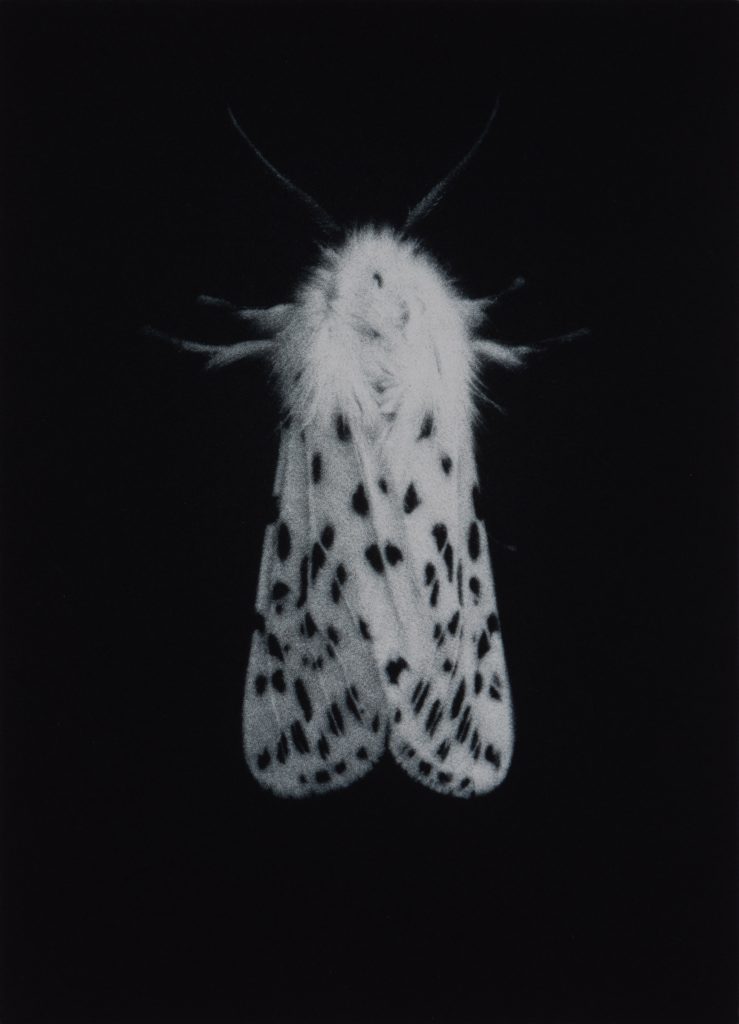

Her use of mezzotint – a labour-intensive tonal engraving technique used widely between the 17th and early 19th century – is key in rendering the nocturnal quality of both the subject matter and the works themselves.

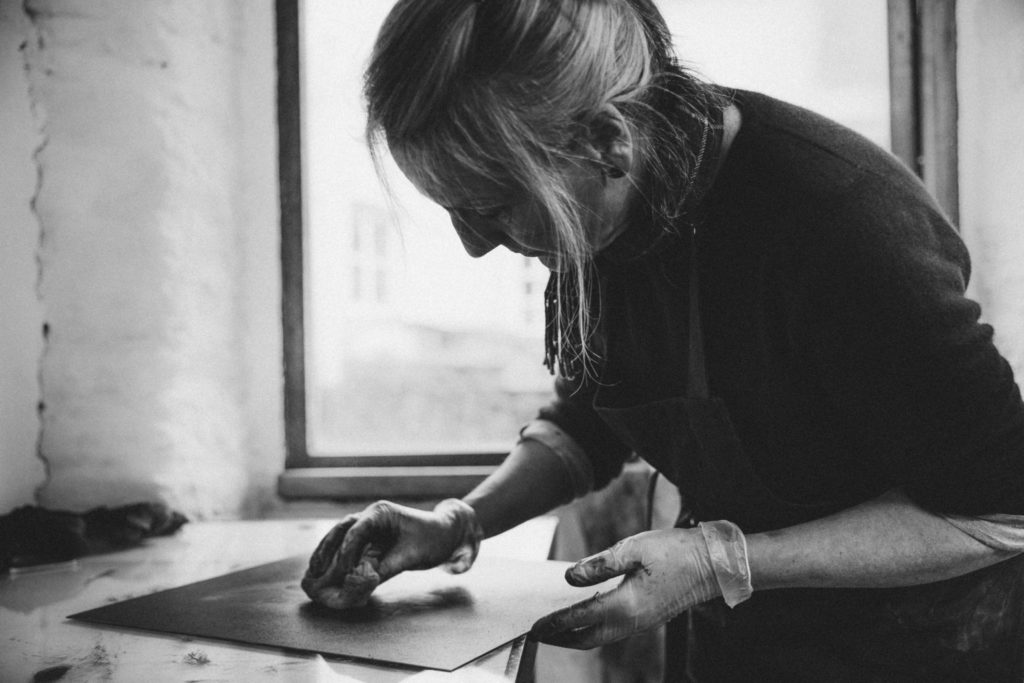

Only through repeated careful and gradual scraping and polishing of the copper mezzotint plate are these soft gradations of tone and rich and velvety blacks revealed. At times presenting themselves in all their astounding detail and at others disappearing altogether, Sarah’s moths hum quietly, a gentle reminder of what may disappear permanently.

“I originally trained in Paris in 16th and 17th century methods of oil painting, and right from the beginning of my art career, I’ve had an interest in old, or arcane, techniques,” she says.

“When I went to the Ruskin [School of Art] in Oxford, I preferred the print room to the art studio and that’s where I did my first mezzotints, but it’s a technique that’s not taught in art schools because it’s too slow – you have to rock the plate in 64 different directions! – and it takes too long for the way art is taught now.

“I always painted and drew as well, but the reason I chose mezzotints for the moths is that with mezzotints, the image is drawn out of the darkness. You scrape and burnish the copper plates to create the lights and half-lights, and that seemed to speak to me very well of moths, as we only half see them: they are half here, half not here.”

A further reason coloured her decision to favour mezzotints. “I’m more comfortable with form and pattern than I am with colour, and we think that moths see in the blue-green spectrum, so I went with the blue spectrum for the prints,” says Sarah.

“If you look at form and pattern, rather than colour, sometimes it has more emotional resonance in monochrome. It’s the same with the impact of black-and-white photographs.”

Such is the meticulous detail in Sarah’s mezzotint prints that it is easy to mistake them for photographs. Not so, there is a reason why a photograph is also known as a “snap”, whereas Sarah’s works of art take weeks, even months.

“At no point is it a photographic process; it’s a hand-drawn and hand-engraved process. Smaller mezzotints take two weeks to create; the 2ft by 3ft Peppered Moth took three months, just to make the plate,” she says. “Then you spend a week printing the plates.

“The conventional size is five inches by seven inches, and it’s not until now that I’ve done such a big one [Peppered Moth] because I had this idea that I didn’t want to spook people even more when they’re already spooked by moths!”

The creation of the Peppered Moth mezzotint is of particular relevance to Castle Howard, whose landscaped gardens provide the ideal location for its own large and varied moth population.

During the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, the species experienced a rapid evolutionary mutation, causing it to turn black.

The Peppered Moth’s unusual colour change saw it darken in response to its habitat that became increasingly polluted and soot covered, allowing it to camouflage and escape predators.

It was in industrial Yorkshire cities, close to Castle Howard, that this melatonic phenomenon was observed in 1848, a full ten years ahead of Charles Darwin’s theories on natural selection. “In Sheffield, for example, they were seen hanging out on birch trees, the moths now completely black,” says Sarah. “And they did that change so very quickly.”

Come the introduction of clean air laws in the 1960s, however, the previous speckled variety returned.

“Camouflage is massively important for moths; they’ve been in an evolutionary race with bats and likewise their caterpillars with plants,” says Sarah. “There are moths that look like bark, bird poo, lichen, leaves.

“They have several defences they use: camouflage and warning signs to scare off birds, such as flashing their colours as a second line of defence, or pretending to drop dead or even making noises to ward off bats.”

Finished in February, the Peppered Moth is now the focal point for the Moth exhibition, not only for its sheer size but to reflect the tenacity of these creatures and the geographical ties to Castle Howard behind this particular species’ fascinating evolutionary story.

Why is Sarah drawn to moths like moths to a flame? “I started doing the mezzotints a few years ago when I was in one of those stages of being disillusioned with the art world as I was finding it narcissistic,” she says, starting out on an answer by a country route. “We are narcissistic as a species and the art world reflected that.

“Though I have many friends in the art world, I was ready for a change. Extinction Rebellion started, and while I wasn’t part of it, many friends were. I don’t like crowds; I like being in the country [she lives near Dartmouth], but I felt artists needed to respond to the biodiversity crisis.

“That’s why I decided to focus on a project rooted in biodiversity, and though this might sound wacky, the moths just offered themselves as a subject.”

How come? “I read Michael McCarthy’s book The Moth Snowstorm: Nature And Joy about the abundance of moths or, rather, lack of abundance, and it was a case of things eliding,” says Sarah, who was delighted that McCarthy subsequently came to Castle Howard on June 5 to give a talk.

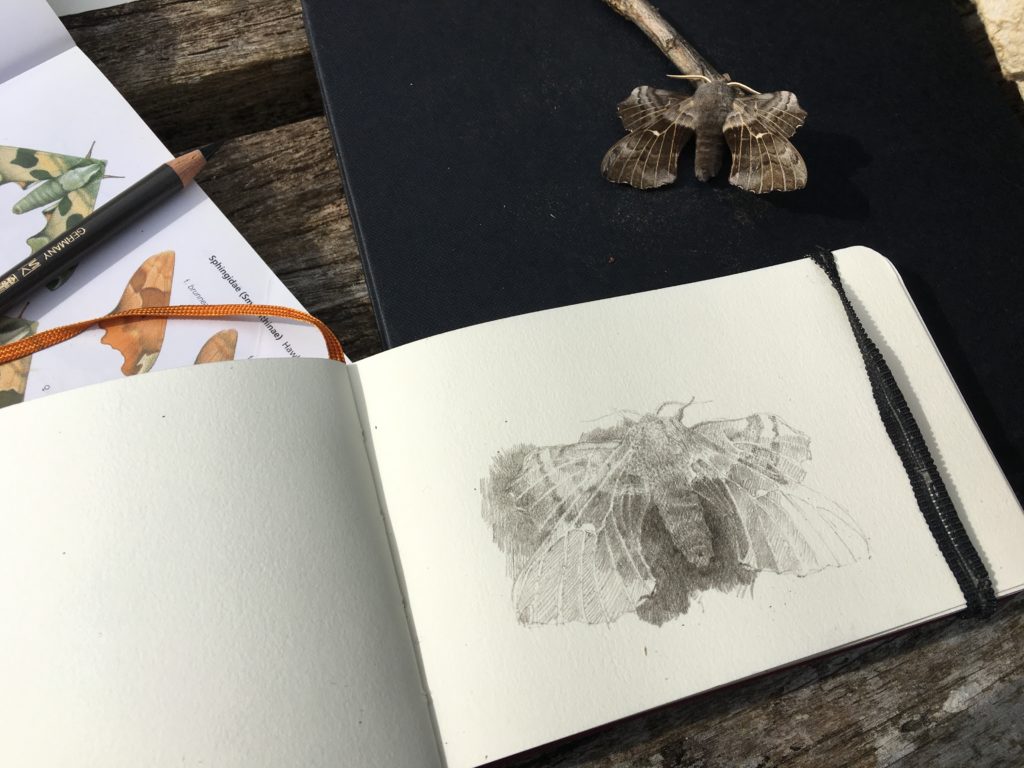

“You don’t get as much to choose from as an artist as you might think, but sometimes a subject chooses you, and as soon as I started drawing moths, much more interesting things started happening for me.”

Such as? “My moth mezzotints are now in collections in America and they’ve been exhibited in Katharinaberg in 2019, Shanghai, and now Castle Howard. So, these invitations keep coming and doors keep opening; it does just feel a little like Alice In Wonderland. Coming up next is Hiroshima in the autumn.”

Will Sarah go to Japan? “No, the sky is for the moths and the birds. I don’t really like flying,” she says.

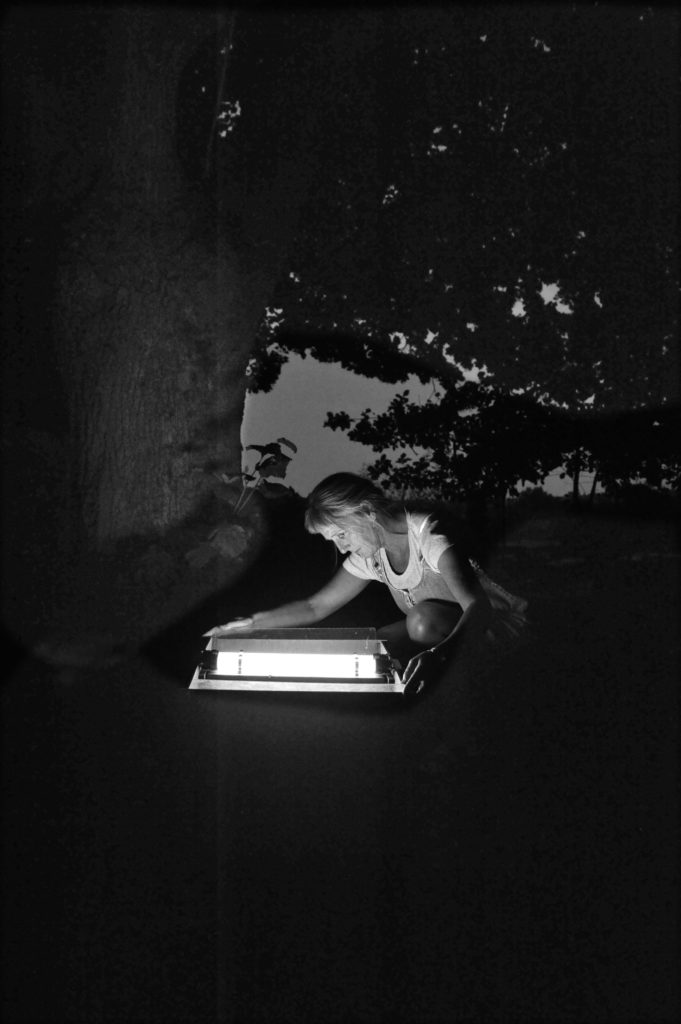

While living onsite as part of her month-long artist’s residency, Sarah has been awaking early to study Castle Howard’s moth population with a view to producing new works in response, including one created publicly during visiting hours.

Visitors have been able to watch her demonstrate the process that goes into making and printing her mezzotints. In addition, she has held a weekly online live streamed event wherein Sarah releases moths caught humanely overnight within Castle Howard’s grounds.

In her temporary workspace alongside the exhibition, Sarah has set up a printing press, courtesy of a York company. “Initially I borrowed a press from a friend, but it wasn’t suitable for mezzotints as you have to apply a lot of pressure,” she says.

“But once I put a request on Instagram, within 12 hours I’d received five suggestions, one advising I should contact Hawthorn Printmaker supplies in Murton. I rang at 9am and by 3pm they’d installed it – for free!”

She has loved her residency: “Nick and Vicki Howard have put me in a Vanbrugh-designed cottage in a walled garden, and I feel very lucky. They keep asking me if I’m comfortable and I just roar with laughter!” she says.

Sarah headed north with one other goal. “Castle Howard has sublime lime tree avenues and I hope to locate a Lime Hawk-moth, which is restricted to such trees,” she said on arrival. “Yorkshire is on the tip of their northernmost territories but I’m hopeful.”

Has she been successful? Maybe we shall learn the answer when Sarah returns to Castle Howard in August to appear on BBC1’s Countryfile.

Sarah Gillespie: Moth runs at Castle Howard until September 5. Entry to the exhibition is via the Stable Courtyard and is free of charge; a gardens ticket is not required.

A REVISED second edition of Sarah’s book Moth is available to buy at £45 from Castle Howard’s gift shop and directly from Sarah’s website at sarahgillespie.co.uk/editions/moth/.

The new hardback features three additional moth prints and an introduction by author and naturalist Mark Cocker, alongside a specially gifted poem by Alice Oswald.

“Common” English Moth Names To Love

1. Dingy Footman

2. Chimney Sweeper

3. Coxcomb

4. Non-conformist [So non-comformist that it is now extinct, alas]

5. Small Fan-footed Wave

6. Pale Brindled Beauty

7. Smoky Wainscot

8. Double-Striped Pug

9. Feathered Gothic

10. Scalloped Oak

11. Setaceous Hebrew Character [‘Setaceous’ means bristly]

12. Garden Grass-veneer

P.S. Micro-moths tend not to have English names, graced only with their Latin name tags. “The English names for moths are our heritage, whereas a lot of the Latin ones are just random,” says Sarah.

In the name of love Moth Fact of the Day:

Moths make noises as a mating call and males can catch pheromones from females kilometres away.

Just One More Thing in defence of moths…

NOVAVAX, the United States-based pharmaceutical company, has used moth cells to create its Covid-19 vaccine.