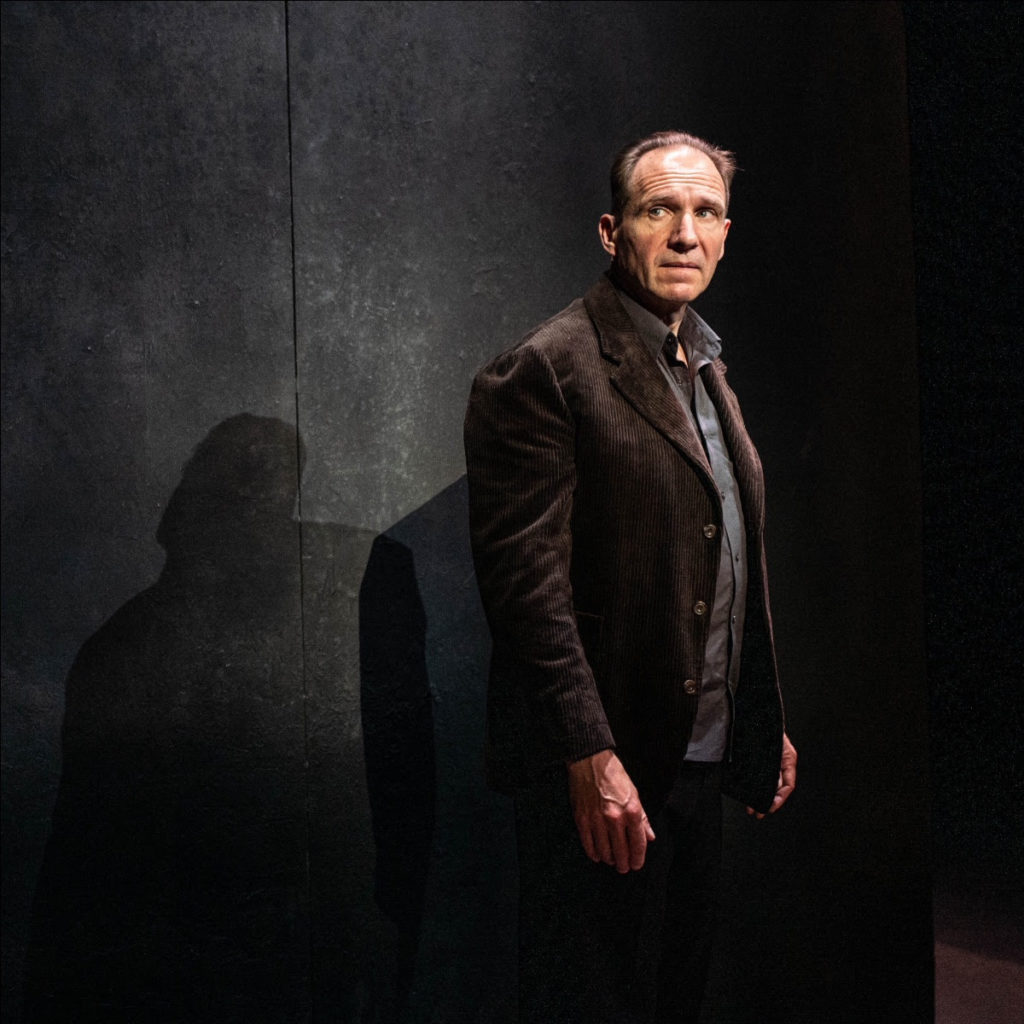

MATTHEW Kelly is performing “like a gazelle” in the 40th anniversary tour of Michael Frayn’s riotous farce Noises Off, despite a knee injury.

“I’m already doing it on two new hips, and off stage I have to walk with a stick,” says the erstwhile Stars In Their Eyes presenter, now 73, who takes to the York Theatre Royal stage from tonight.

“I twisted my knee on the set about a year ago on the first tour run. I thought, ‘I’m not going to have any more surgery; I’ll treat it with physiotherapy’, and that’s what I’ve done. It gets me a seat on the Tube every time!

“The knee’s getting better and I’ve kind of got used it, having had to use sticks when I was getting the hips done.”

Matthew takes the role of Selsdon Mowbray, an old actor with a drink problem, “for which I’ve done a lot of research”, he jokes.

“The play’s been going for 42 years, and I was up for the first takeover 40 years ago, when I was invited to follow Nicky Henson in the lead role in the original production.”

Watching Henson’s supreme performance, however, Matthew decided against taking up the invitation. When the chance came to play Selsdon Mowbray, four decades later, this time he jumped at it, new hips and all.

On the first itinerary, he played opposite Felicity Kendal; now he is joined by fellow 73-year-old Liza Goddard in Theatre Royal Bath’s touring revival, directed by Lindsay Posner, who staged Richard III and Romeo And Juliet in York’s first season of Shakespeare’s Rose Theatre productions in 2018.

Structured as a play within a play over three acts, Frayn’s chaotic comedy follows the on and off-stage antics of a hapless touring theatre company stumbling its way through the fictional farce, Nothing On, from shambolic final rehearsal to a disastrous matinee, seen silently from backstage, before their catastrophic last performance in Stockton-on-Tees.

If you have enjoyed Mischief’s visits to York with The Play That Goes Wrong and Magic Goes Wrong in recent years, they echo Frayn’s forerunner, a comedy rooted in calamities, pratfalls and slapstick as a cast at war with each other strives desperately to keep a performance on track amid the mayhem.

“What makes it work, and the only way it can work, is for the company to be really close, really bonded, and absolutely in tune with each other, which we are,” says Matthew. “If you get one thing wrong, it can throw the whole play out of kilter.

“I always have good times with companies, but this company is an absolute delight to work with. Having to do three matinees a week, it’s absolutely killing us. There’s no-one having an affair as we’re too knackered!”

Michael Frayn has supported the 40th anniversary tour at every opportunity, as well as tweaking the script. “He’s now 90, and he’s been with us since the start, coming to the opening night when I first did the show with Felicity last year, opening at Bath, and then when we went into the West End,” says Matthew.

“He’s told us it’s the best ever production of the play, though he probably always says that. He’s kind and encouraging, and you just know he’s like that with every company.”

The revival of Noises Off is perfectly timed after the pandemic sent theatres into cold storage. “It’s a love letter to theatre that really lifts the spirit. You hear people rolling around with laughter throughout the show,” says Matthew.

This is the reward for the cast’s meticulously timed comedic performances. “We only had three weeks’ rehearsal for the second tour, and I was the only original member of the cast still in the show. So when we opened in Birmingham, we were still rehearsing during the day as well as performing at night.”

In keeping with the play, things can go wrong. “At one show, one of the girls accidentally left a bunch of flowers on stage, on the upper level, and the next thing that happened was the play began to fall to bits – and the whole place went nuts!” recalls Matthew.

“It wasn’t funny, it was terrifying, but somehow, we got back on track. After the show, I saw a friend, and when I told them it had all gone wrong, they said they’d never noticed! But when things go wrong, they’re only funny to the people who are there watching the show.”

Mind you, actors can play jokes on each other too, like when Matthew was performing Arnold Ridley’s The Ghost Train with Julie Walters and Bill Nighy in Aberystwyth. “When we’re locked in the waiting room, everyone changes place in the dark. Each show we’d have scuffles, where everyone would try to shove each other off stage!” he reveals.

“One Wednesday matinee, when the lights came back on, there was only me on stage, and the rest of the cast were sitting in the front row, arms folded, all looking at me.”

Don’t take it too seriously, Matthew advises himself and those around him in the acting world. “Honestly, no-one cares! We’re only playing in the dressing -up box,” he says.

That said, he would love to play King Lear, the third age role that veteran Yorkshire Shakespearean actor Barrie Rutter has said “you should do twice: once when you can do it, and once when you have to do it”.

Kelly’s Lear will surely happen one day. In the meantime, next up, once the Noises Off tour ends in January, will be the world premiere of Jim Cartwright’s The Gap, a two-hander with Denise Welch, running at Hope Mil Theatre, Manchester, from February 9 to March 9.

“It’s about two teenagers running away to London in the Sixties and reuniting much later,” says Matthew. “I first did it as a one-act play about seven years ago, then made a film of it with Sue Johnston during the pandemic, and now Jim has expanded it into a full play.”

The Gap follows the audacious adventures of Walter and Corral. “He’s back up north, she’s still down south,” the theatre website says. “They haven’t seen each other for 50 years, not since their Soho days, back in the swinging ’60s. A chance phone call reunites them for one magical night and in next-to-no time, they’re back to their old tricks.”

What is “the gap”, Matthew? “Cultural? Geographical? I tell you what it is,” he says. “It is the gap of flesh between stocking top and knicker ridge that drives men wild!”

Noises Off, York Theatre Royal, tonight (31/10/2023) until Saturday, 7.30pm nightly plus 2pm Thursday and 2.30pm Saturday matinees. Box office: 01904 623568 or yorktheatreroyal.co.uk.

Did you know?

MATTHEW Kelly appeared previously at York Theatre Royal in two Alan Bennett plays: Kafka’s Dick, with his son Matthew Rixon, in 2001 and The Habit Of Art, a fictional meeting between York-born poet W H Auden and composer Benjamin Britten, exploring friendship, rivalry, heartache and the joy, pain and emotional cost of creativity, in 2018.