The fez, the spectacles and the bow tie: Damian Williams’s Tommy Cooper, Bob Golding’s Eric Morecambe and Simon Cartwright’s Bob Monkhouse in The Last Laugh. Picture: Pamela Raith

AFTER five hollow weeks in New York, Paul Hendy’s love letter to the quintessentially British – even English – humour of Tommy Cooper, Eric Morecambe and Bob Monkhouse opens its UK tour in old York.

Morecambe & Wise may have appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show 16 times, Cooper on six occasions too, but if ever affirmation were needed that the USA and UK are divided by a common language, then the Big Apple audiences’ bewilderment at their reactivated larks in Hendy’s 90-minute play provided it.

Unlike last summer’s Edinburgh Fringe premiere and February and March’s West End run at the Noel Coward Theatre, it was more a case of ‘no laugh’, rather than ‘last laugh’, judging by the New York recollections of Hendy’s cast at the question-and-answer session that followed Wednesday’s matinee.

Hendy just happened to be there too, adding further insight into his affectionate play, and his hand-picked cast – who first appeared in his 19-minute film version in 2016 – will be on hand after each performance to take more questions. Well worth staying for their banter, nostalgia and comedic camaraderie, prompted by questions deposited in a Cooper fez in the interval.

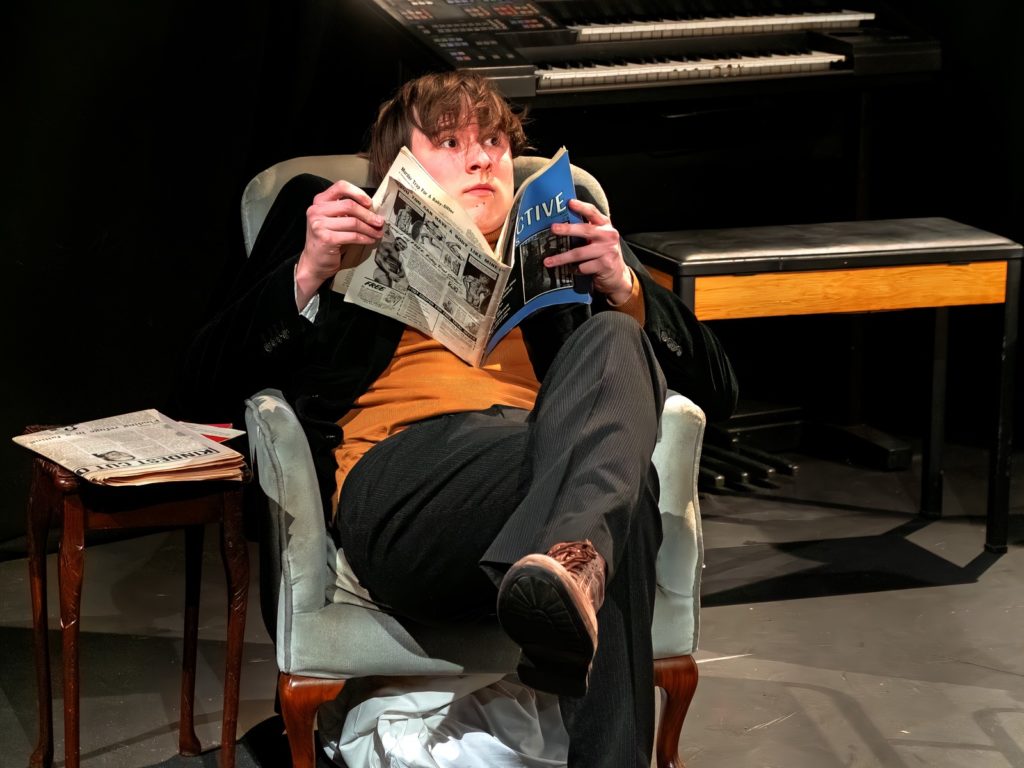

Damian Williams’s Tommy Cooper, minus trousers, Bob Golding’s Eric Morecambe and Simon Cartwright’s Bob Monkhouse in a moment of musical camaraderie in The Last Laugh. Picture: Pamela Raith

If Hendy’s name is familiar to you, he is the writer of York Theatre Royal’s pantomimes under the fruitful partnership with his Evolution Productions company since 2020. You will know his style too: meticulous crafting of puns, putdowns and pratfalls, allied to a rebellious streak and a passion for storytelling.

Those qualities will be seen again in Sleeping Beauty from December 2 to January 4 2026, and they are writ large in The Last Laugh, his exploration of what makes comedy work, what drives comedians to perform and at what cost, and why the laughs last long after their passing.

Hendy, a jokesmith who lets others do the telling, has chosen his comedians carefully for his study: Cooper and Morecambe, who died within six weeks of each other in 1984, were naturally funny, but whereas Cooper merely had to walk on stage to engender laughs, using silence like no-one else, Morecambe needed partners, whether Ernie Wise on stage, or writers for him to then apply his alchemical gifts of timing, mannerism and mischief.

Hendy, by his own admission, is closer to Monkhouse, the craftsmen who would chisel away at a gag like a sculptor until it had the right balance and comic weight, honed and polished to the last word. He kept his jokes in books; he knew who wrote every famous line; he knew how to deliver a punchline.

After all, it was Monkhouse who quipped: “People used to laugh at me when I said I wanted to be a comedian. Well, they’re not laughing now.”

The Last Laugh writer-director Paul Hendy

You can imagine Hendy applying such fastidious skills when writing The Last Laugh, pulling the strings as a writer must to make a piece of theatre with resonance and meaning, rather than rely on an overload of familiar jokes.

He does so by placing the comedy triumvirate in a dressing room of memories, where one wall is filled with black-and-white portraits of comedians, all dead, from Sid Field to Sid James, with the space for one more. Then he lets them chat, lock horns, reflect, perform to each other, and dress for their next performance.

He entrusts the roles to two of his regular dames, Bob Golding and Sheffield Lyceum’s Daman Williams, and Simon Cartwright, who first made his name as an impressionist. Golding first played Eric 16 years ago in his own Morecambe show; Williams had wanted to follow Cooper on to the stage since childhood days; Cartwright knew Monkhouse, working on his act with him.

Williams’s Cooper enters first, after a spluttering and fizzing of the lights that frame each dressing room mirror and the pre-show ghostly sounds of comedians past. Williams, in his underwear, is wearing huge yellow bird’s legs.

In New York, a woman objected to his lack of trousers. “It was going to be a long night,” Williams shrugged in the Q&A. He goes on to give a towering performance as the play’s fulcrum, not an impression, but a full picture of a giant of comedy, amusingly dismissive of others, a quick thinker, an astute observer and both inventive and re-inventive.

Damian Williams’s Tommy Cooper: Comedy magic in The Last Laugh. Picture: Pamela Raith

Cartwight has the Monkhouse manner and voice off to a T, a man of candour, kindness, precision, admiration for others and forensic knowledge, with Hendy dropping in stories that may not be familiar but make for a rounded portrait.

Golding’s love of Eric is in every moment, every movement, from the pipe smoking to the chirpy demeanour, while resisting too much twitching of the spectacles. Again, as with Cooper and Monkhouse, Hendy judges so well what to include of Morecambe’s life story, in particular his resolute devotion to working with Wise.

Who has The Last Laugh? No, it would be wrong to give away the ending, but let’s say it could not be more moving. Joy and sadness, the two faces of theatre, are never more interlocked than in Hendy’s finale.

We miss these comic titans, the fez, the spectacles and Bob’s books, but you will have the first laugh, the last laugh and so many more in between in their memory.

The Last Laugh, Grand Opera House, York, 7.30pm tonight; 2.30pm and 7.30pm tomorrow. Box office: atgtickets.com/york.

The tour poster for Paul Hendy’s The Last Laugh

The Last Laugh cast and writer visit Borthwick Institute’s archive of Eric Morecambe notebook and diaries

The Last Laugh actors Simon Cartwright (Bob Monkhouse), Damian Williams (Tommy Cooper) and Bob Golding (Eric Morecambe) take a look at the Borthwick Institute comedy archives

THE cast and writer of The Last Laugh undertook an emotional trip to the Borthwick Institute for Archives at the University of York on June 11 to view the notebooks and newly acquired diaries of Eric Morecambe.

Writer-director Paul Hendy and actors Bob Golding, Damian Williams and Simon Cartwright, who play Morecambe. Tommy Cooper and Bob Monkhouse respectively, were joined by the archive team for a private viewing.

The collections include original material for the Morecambe and Wise 1977 Christmas BBC Special, written in Morecambe’s distinctive handwriting, together with notebooks, diaries and jokes owned previously by legends of British comedy.

Gary Brannan, keeper of archives and research collections at the Borthwick Institute, with The Last Laugh actors Damian Williams, Simon Cartwright and Bob Golding

Hendy said: “As a lifelong fan of Eric Morecambe, it’s been absolutely fascinating to visit the archive. To be able to read Eric’s joke books, written in his own hand, is incredible and actually quite emotional”.

The Borthwick Institute’s comedy collections, acquired by the university, provide an insight into the history of British entertainment. Gary Brannan, keeper of archives and research collections, said: “It’s been a delight to welcome the cast of The Last Laugh to Borthwick and we have loved seeing them connect and with our amazing archives.

“We always say that archives aren’t just records of the past; they are a source of modern creativity, so it has been wonderful to see the cast bring this material to life.”

The actors were thrilled to look at the original documents. Cartwright said: “The archive has been an absolute joy to discover. I was particularly thrilled to find two original radio scripts written by Bob Monkhouse and his writing partner, Denis Goodwin. It serves as a reminder of Bob’s longevity in the industry – over 60 years.”

The Last Laugh writer-director Paul Hendy, centre, with Gary Brannan and Simon Cartwright studying documents at the Borthwick Institute