GO forth and multiply the chance to see the summer spurt of theatre, musicals and outdoor shows, urges Charles Hutchinson, who also highlights big gig news for autumn and March 2022.

Breaking the library hush: Next Door But One in Operation Hummingbird, in York, today and August 12

YORK community arts collective Next Door But One are teaming up with Explore York for a library tour of Matt Harper-Harcastle’s 45-minute play Operation Hummingbird.

James Lewis Knight plays Jimmy and Matt Stradling, James, in a one-act two-hander that takes the form of a conversation across the decades about a sudden family death, realising an opportunity that we all wish we could do at some point in our life: to go back and talk to our younger self.

Today’s Covid-safe performances are at 3.30pm at New Earswick Folk Hall and 7pm, Dringhouses Library; August 12, York Explore, 2pm, and Hungate Reading Café, 7pm. Box office: nextdoorbutone.co.uk.

Play launch of the week outside York: Esk Valley Theatre in Shirley Valentine, Robinson Institute, Glaisdale, near Whitby, tonight until August 28

ESK Valley Theatre complete a hattrick of Willy Russell plays with Shirley Valentine from tonight, under the direction of artistic director Mark Stratton as usual.

In Russell’s one-woman show, Coronation Street star Ashley Hope Allan plays middle-aged, bored Liverpool housewife Shirley in a story of self-discovery as she takes a holiday to Greece with a friend, who promptly abandons her for a holiday romance. Left alone, Shirley meets charming taverna owner Costas. Box office: 01947 897587 or at eskvalleytheatre.co.uk.

Musical of the week outside Leeds, Heathers The Musical, Leeds Grand Theatre, tonight until August 14

HEATHERS The Musical launches its touring production in Leeds from tonight with choreography by Gary Lloyd, who choreographed the debut York Stage pantomime last Christmas.

Produced by Bill Kenwright and Paul Taylor-Mills and directed by American screen and stage director Andy Fickman, this high-octane, dark-humoured rock musical is based on the Winona Ryder and Christian Slater cult teen movie.

The premise: Westerberg High pupil Veronica Sawyer (Rebecca Wickes) is just another nobody dreaming of a better day, until she joins the impossibly cruel Heathers, whereupon mysterious teen rebel JD (Simon Gordon) teaches her that it might kill to be a nobody, but it is murder being a somebody. Box office: 0113 243 0808 or at leedsheritagetheatres.co.uk.

Art event of the week: Ryedale Open Studios, Saturday and Sunday and next weekend, 10am to 5pm each day

THE newly formed Vault Arts Centre community interest company, in Kirkbymoorside, is coordinating this inaugural Ryedale Open Studios event, celebrating the creativity and artistic talent of Ryedale and the North York Moors.

Artists, makers and creators will be offering both an exclusive glimpse into their workplaces and the opportunity to buy art works directly. Full details of all 33 artists can be found at ryedaleopenstudios.com; a downloadable map at ryedaleopenstudios.com/map.

Hit and myth show of the week: Eurydice, Theatre At The Mill, Stillington Mill, near York, Saturday and Sunday, 7.30pm

THIS weekend, Serena Manteghi returns to the play she helped to create with writer Alexander Wright, composer Phil Grainger and fellow performer Casey Jane Andrews with Fringe award-winning success in Australia in 2019.

Manteghi, a tour de force in the Stephen Joseph Theatre’s Build A Rocket, will be joined by Grainger for the tale about being a daily superhero and not giving in to the stories we tell ourselves.

Woven from spoken word and soaring live music, Eurydice is the stand-alone sister show to Orpheus; her untold story imagined and reimagined for the modern-day and told from her perspective. Box office: tickettailor.com/events/atthemill/.

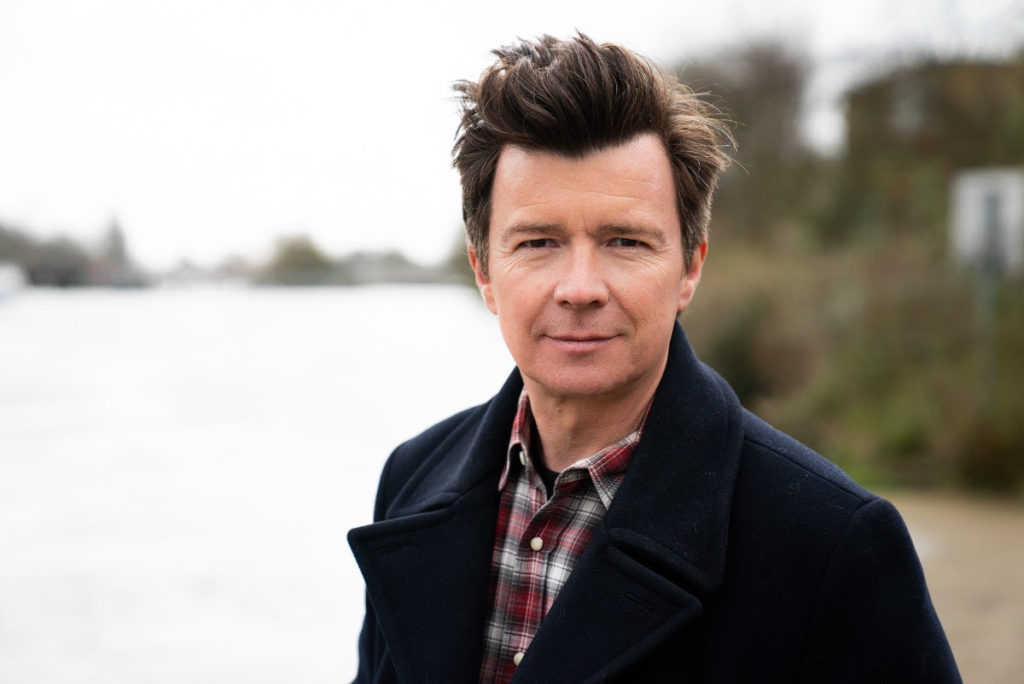

Yorkshire gig of the week outside York: Kaiser Chiefs, Scarborough Open Air Theatre, Sunday, gates open at 6pm

LEEDS lads Kaiser Chiefs promise a “no-holds-barred rock’n’roll celebration” on their much-requested return to Scarborough OAT after their May 27 2017 debut.

“We cannot wait to get back to playing live shows again and it will be great to return to this stunning Yorkshire venue,” says frontman Ricky Wilson. “We had a cracking night there in 2017, so roll on August 8!”

Expect a Sunday night of such Yorkshire anthems as Oh My God, I Predict A Riot, Everyday I Love You Less And Less, Ruby, Never Miss A Beat and Hole In My Soul. Box office: scarboroughopenairtheatre.com.

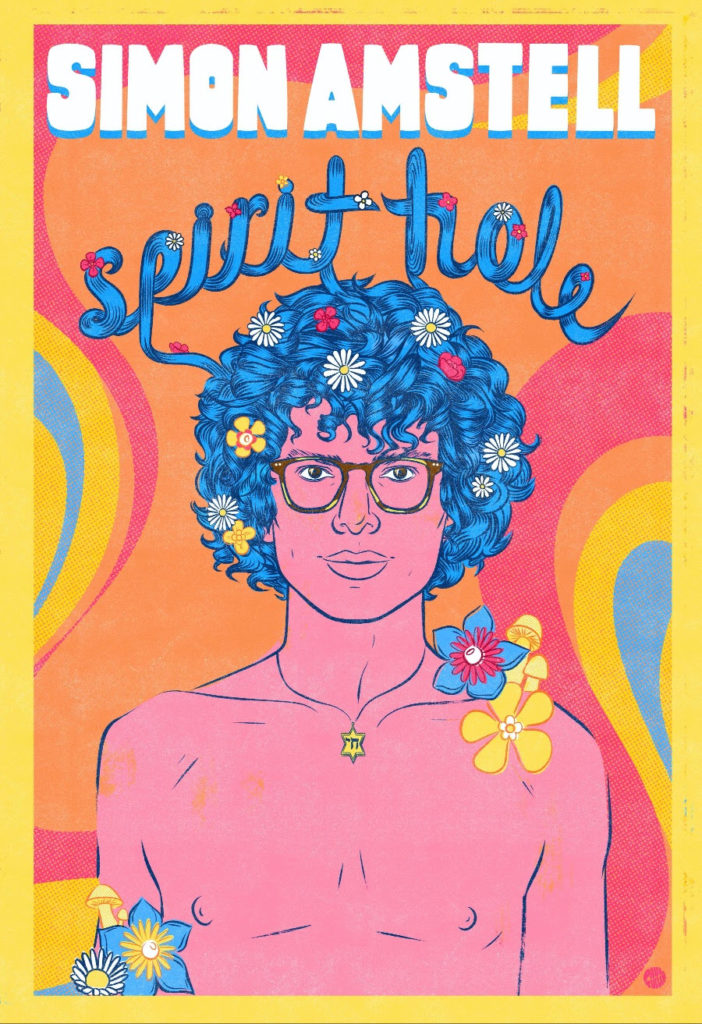

Comedy gig announcement of the week: Simon Amstell, Spirit Hole, Grand Opera House, York, September 25, 8pm

INTROSPECTIVE, abjectly honest comedian Simon Amstell will play the Grand Opera House, York, for the first time since 2012 on his 38-date Spirit Hole autumn tour.

Agent provocateur Amstell, 41, will deliver a “blissful, spiritual, sensational exploration of love, sex, shame mushrooms and more” on a tour with further Yorkshire gigs at The Leadmill, Sheffield, on September 12 and Leeds Town Hall on October 1.

York tickets are on sale at atgtickets.com/venues/grand-opera-house-york/; York, Sheffield and Leeds at ticketmaster.com.

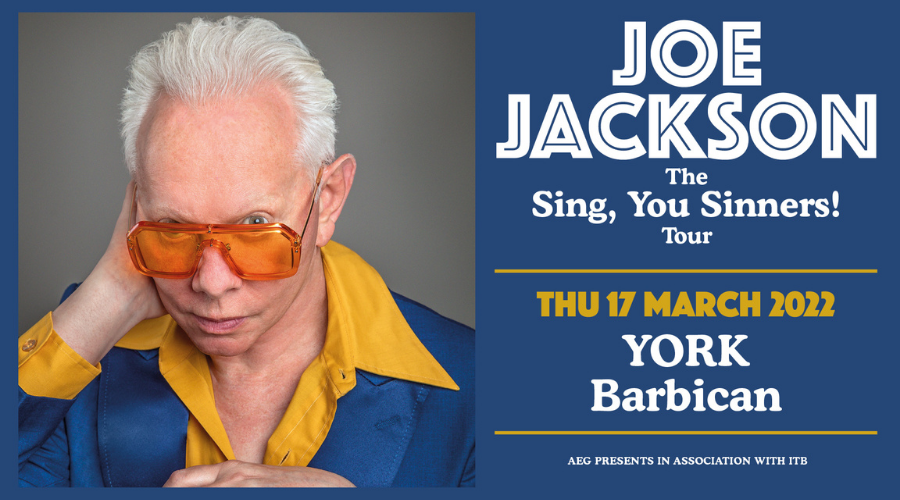

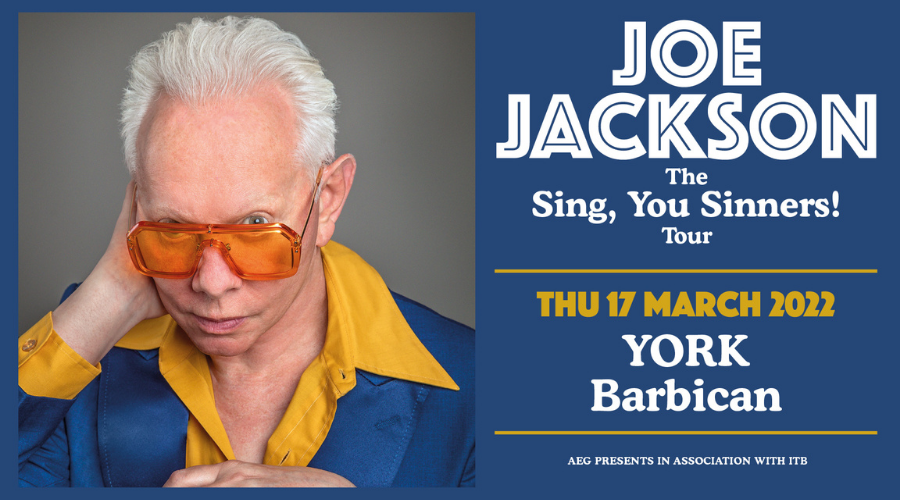

York gig announcement of the week: Joe Jackson, York Barbican, March 17 2022

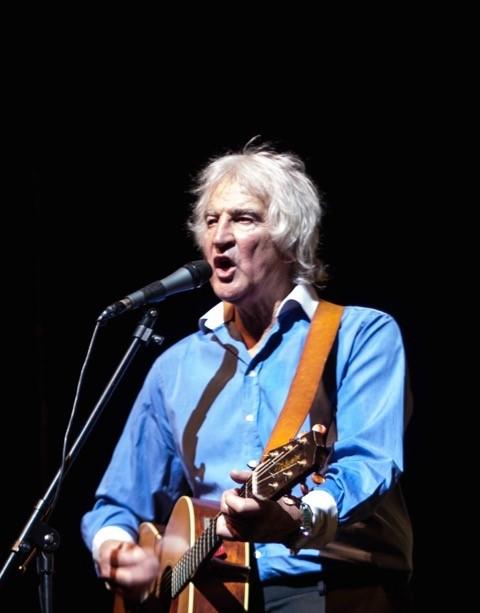

JOE Jackson will play York for only the second time in his 43-year career on his Sing, You Sinners! tour next year.

Jackson, who turns 67 on August 11, will perform both solo and with a band at York Barbican in the only Yorkshire show of his 29-date British and European tour, promising hits and new material.

“We’ve been dealing with two viruses over the past two years, and the worst – the one we really need to put behind us – is Fear,” he says. “Love is the opposite of fear, so if you love live music, come out and support it!” Box office: yorkbarbican.co.uk.