A MUSICAL with Bob Dylan songs, Wilde wit with chart toppers, heavenly disco and Sunday fairytales promise intrigue and variety in Charles Hutchinson’s diary.

Musical of the week: Girl From The North Country, York Theatre Royal, Tuesday to Saturday

WRITTEN and directed by Irish playwright Conor McPherson, with music and lyrics by Bob Dylan, Girl From The North Country is an uplifting and universal story of family and love that boldly reimagines Dylan’s songs “like you’ve never heard them before”.

In 1934, in an American heartland in the grip of the Great Depression, a group of wayward souls cross paths in a time-weathered guesthouse in Duluth, Minnesota. Standing at a turning point in their lives, they realise nothing is what it seems as they search for a future, hide from the past and find themselves facing unspoken truths about the present. Box office: 01904 623 568 or yorktheatreroyal.co.uk.

Children’s show of the week: Once Upon A Fairytale, At The Mill, Stillington, near York, Sunday, 10am to 12 noon

IN York company Story Craft Theatre’s new show for children aged two to eight, Sunday’s audience will travel through a host of favourite fairytales and meet familiar faces along the way: Little Red Riding Hood, The Gingerbread Man and some hungry Bears to name but a few.

Storytellers Janet-Emily Bruce and Cassie Vallance say: “You’re welcome to arrive any time from 10am as we’ll be running craft activities until 10.45am. The interactive adventure will begin at 11am under the cover of our outdoor theatre, and there’ll be colouring-in sheets and a scavenger hunt you can do too.” Box office: atthemill.org.

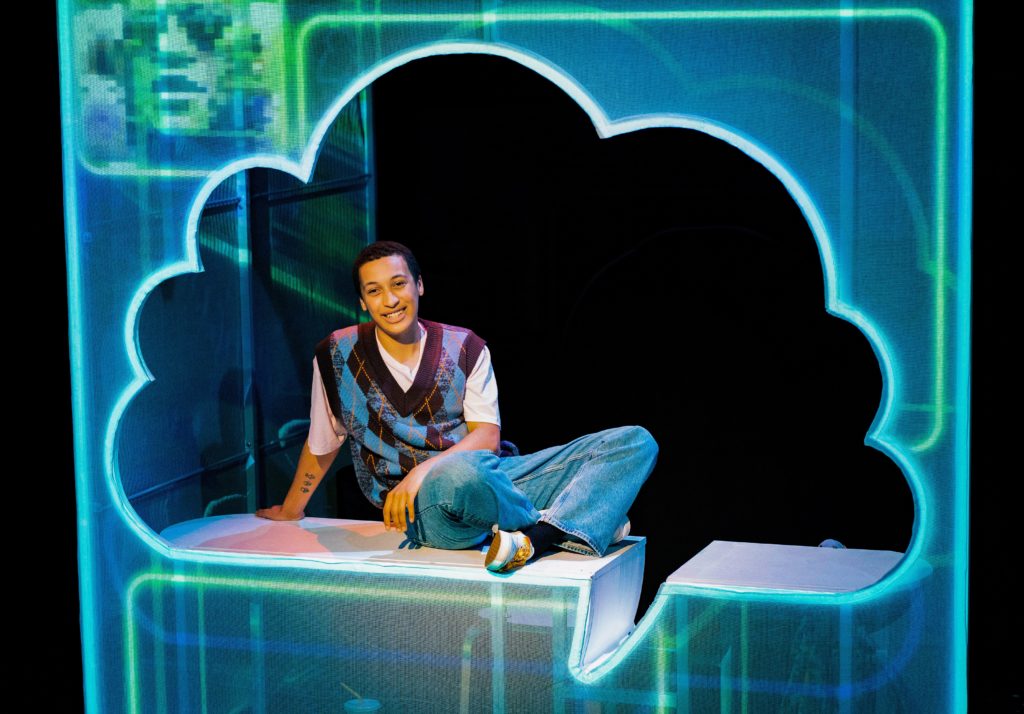

A walk on the Wilde side to a different beat: The Importance Of Being Earnest, Leeds Playhouse, Monday to September 17

DANIEL Jacob swaps his drag queen alter ego Vinegar Strokes for the iconic Lady Bracknell at the heart of Denzel Westley-Sanderson’s Black Victorian revamp of Oscar Wilde’s sharpest and most outrageous comedy of manners.

Premiering in Leeds before a UK tour, this Leeds Playhouse, ETT and Rose Theatre co-production “melds wit with chart-toppers, shade and contemporary references in a sassy insight into Wilde’s satire on dysfunctional families, class, gender and sexuality”. Box office: 0113 213 7700 or leedsplayhouse.org.uk.

Disco nostalgia of the week: Tavares, Greatest Hits Tour 2022, York Barbican, Wednesday, 7.30pm

GRAMMY Award-winning, close harmony-singing R&B brothers Chubby, Tiny and Butch Tavares, from Providence, Rhode Island, bring their Greatest Hits Tour to York.

At their Seventies peak, accompanied by their Cape Verdean brothers Ralph and Pooch, they filled disco floors with It Only Takes A Minute Girl, Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel, She’s Gone and More Than A Woman, from the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack. Box office: yorkbarbican.co.uk.

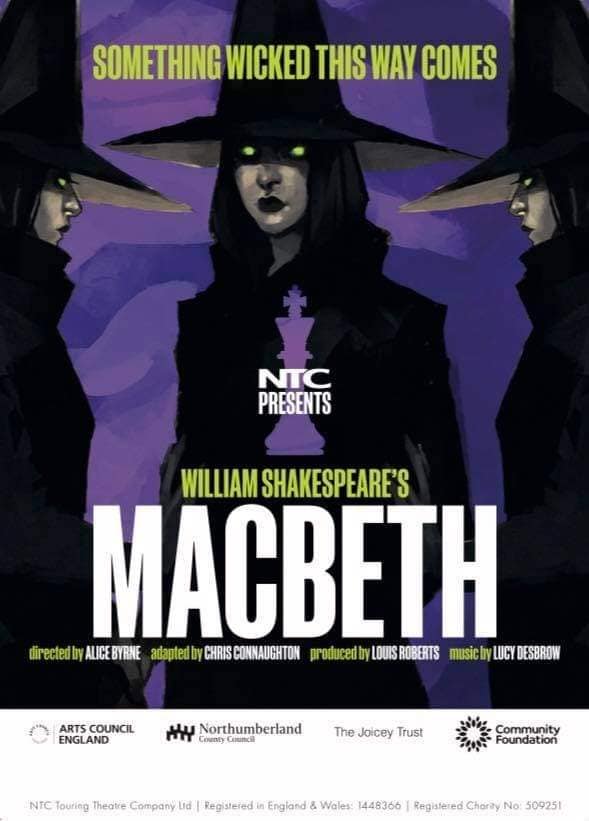

Something wicked this way comes: Northumberland Theatre Company in Macbeth, Stillington Village Hall, near York, Thursday; Pocklington Arts Centre, September 29, both 7.30pm

YORK actor Claire Morley stars in Chris Connaughton’s all-female, three-hander version of Shakespeare’s “very gruesome” tragedy Macbeth, directed by Northumberland Theatre Company associate director Alice Byrne for this autumn’s tour to theatres, community venues, village halls and schools.

This streamlined, fast-paced, extremely physical production with original music will be told largely from the witches’ perspective, exploring ideas of manipulation through the media and other external forces. Expect grim, gory grisliness to the Mac max in two action-packed 40-minute halves. Box office: Stillington, 01347 811 544 or on the door; Pocklington, 01759 301547 or pocklingtonartscentre.co.uk.

Charity concert of the week: A Night To Remember, York Barbican, Thursday, 7.30pm

BIG Ian Donaghy’s charity fundraiser returns 922 days after he last hosted this fast-moving assembly of diverse York singers and musicians.

Taking part will be members of York party band Huge; Jess Steel; Heather Findlay; Beth McCarthy; Simon Snaize; Gary Stewart; Graham Hodge; The Y Street Band; Boss Caine; Las Vegas Ken; Kieran O’Malley and young musicians from York Music Forum, all led by George Hall and Ian Chalk.

Singer and choir director Jessa Liversidge presents her inclusive singing group, Singing For All, too. Proceeds will go to St Leonard’s Hospice, Bereaved Children Support York and Accessible Arts and Media. Tickets update: still available at yorkbarbican.co.uk.

Exhibition launch of the week: Contemporary Glass Society, Bedazzled, Pyramid Gallery, Stonegate, York, September 10 to October 30

THE Contemporary Glass Society will celebrate its 25th anniversary of exhibiting at Pyramid Gallery with a show featuring 60 works by 25 glass artists, chosen by gallery owner Terry Brett and the society’s selectors.

For this landmark exhibition in Pyramid’s 40th anniversary year, the society wanted a theme and title that suggested celebratory glitz for its silver anniversary. Cue Bedazzled.

The styles and techniques span engraving, blowing, fusing, slumping, casting, cane and murine work, flame working, cutting, polishing, brush painting and metal leaf decoration. A second show, Razzle Dazzle, will include small pieces that measure no more than five by five inches by 60 makers.

Gig announcement of the week: KT Tunstall, York Barbican, February 24 2023

SCOTTISH singer-songwriter KT Tunstall will return to York for the first time since she lit up the Barbican on Bonfire Night in 2016 on next year’s 16-date tour.

The BRIT Award winner and Grammy nominee from Edinburgh will showcase songs from her imminent seventh studio album, Nut, set for release next Friday on EMI. Box office: kttunstall.com and yorkbarbican.co.uk.