ASSOCIATE director Amy Leach notches a hattrick of make-you-think-anew Shakespeare productions at Leeds Playhouse with her psychological thriller, Macbeth, after her modern Yorkshire industrial take on Romeo & Juliet in 2017 and Hamlet with Tessa Parr’s female Hamlet in 2019.

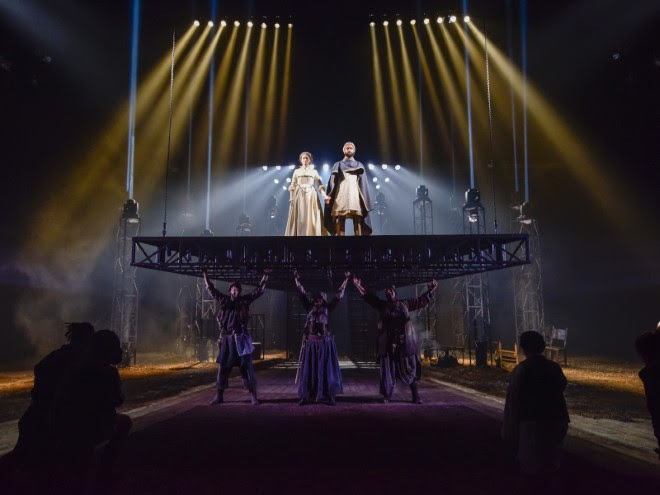

A huge drawbridge hangs heavy over Hayley Grindle’s stage. Searchlights scan the auditorium from metallic towers spread out like a forest. Fog encroaches. Deafening noise bursts through the air. This could be the start of an arena rock concert, but then, look more closely. To one side is a puddle of water; the ground is muddy.

Then listen to the Witches’ opening words; re-shaped, re-ordered, with new rhythms, their sound as important as their meaning. What’s this? Macbeth (Tachia Newall) and Lady Macbeth (Jessica Baglow) are cradling a new-born baby, only for the bairn to die within a heartbeat.

In the Playhouse’s wish to “explore the damaging physical, spiritual and psychological effects of treachery on those who seek power at any cost”, Leach has grabbed the bull by the horns, putting child loss, lineage and legacy at the heart of the Macbeths’ behaviour, the acts of murder, the need to eliminate all threats to their ill-gotten power.

Leach then takes it even further, Baglow’s Lady Macbeth being pregnant when she says “unsex me here” and later suffering a miscarriage as blood seeps through her nightgown. Come the finale, Leach adds new text to give a foretaste of Banquo’s son, Fleance, becoming king as the Three Witches had prophesied.

Those Three Witches are typical of Leach and Leeds Playhouse artistic director James Brining’s “commitment to accessible and inclusive theatre-making”, as is the participation of the blind Benjamin Wilson as associate director and audio description consultant.

Among the witches, Karina Jones is visually impaired and Charlotte Arrowsmith is profoundly deaf, while Ashleigh Wilder identifies as “a queer, Black, neurodivergent non-binary person”. Interestingly, Shakespeare’s “weird sisters” are not weird, or alien, in the way they are often played, but are as wild as the landscape instead.

Arrowsmith also plays Lady MacDuff, partnered by the profoundly deaf Hull actor Adam Bassett as MacDuff. Tom Dawze’s Lennox vocally interprets the sign language, complementing the intensity of Bassett’s expressive face, hands and arms with the staccato rhythms of his speech.

Not only do lighting designer Chris Davey’s aforementioned searchlights induce a sense of paranoia, but there are relentlessly oppressive natural elements to the fore too, along with the sound and fury of machismo war. These are all big, muscular, mud-and-blood splattered men, except for Kammy Darweish’s surprisingly jovial King Duncan; their physicality being emphasised by Georgina Lamb’s movement direction. Likewise, Nicola T Chang’s sound design adds to the cacophony.

Macbeth’s vaulting ambition may in part be represented by the drawbridge, crowned when on top of it, but broken beneath it, but Leach’s production is deeply human amid the technology.

In the relationship of Newall’s reactionary Macbeth and Baglow’s more intuitive Lady Macbeth, the shifting sands become less about calculating mind games, controlled by her, more about brute physicality and brutal will, imposed by him, as intense love and mutual hopes are snuffed out in the face of ultimate destiny being beyond their control, whether shaped by supernatural witchcraft or the resurrection of natural order.

Newall’s Macbeth begins as the soldier’s soldier; his soliloquies remain the stuff of northern plain speaking, rather than poetic airs, amid the fevered actions of his bloody rise and fall.

Above all, Leach puts Lady Macbeth’s motives under the spotlight, and if purists feel she has gone too far in doing so, the reality is that Baglow’s performance is all the better, more rounded, for it. Risk-taking change can be liberating, rather than be judged as taking liberties.

Review by Charles Hutchinson