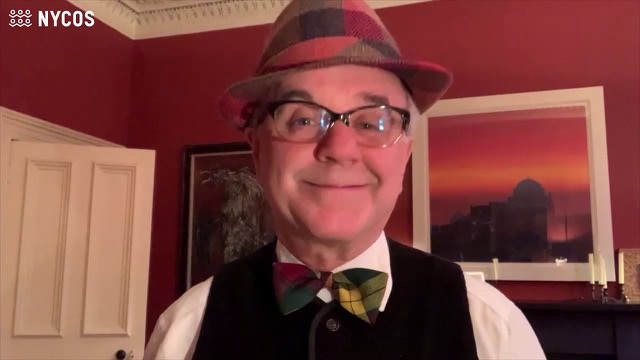

Conductor and composer Eric Whitacre. Picture: Marc Royce

THE concert opened with a charming theatrical gesture: the choir entered the auditorium in single file, splitting symmetrically to surround the audience — with conductor Eric Whitacre positioned halfway up the central aisle — to perform the composer’s Lux Aurumque.

I’ve attended a number of concerts here — almost all of them orchestral — and all compromised by the venue’s generous acoustic. That’s hardly surprising, given that Hovingham Hall’s concert space was originally the North Yorkshire estate’s 18th-century riding school. But not this time. The choral sound resonated beautifully, the balance was impeccable and so was the singing.

Not only is Eric Whitacre a superb composer and a highly accomplished conductor, but he’s also completely at ease in his role as presenter. Instantly engaging and often funny, he gave us a deeper understanding of the choral works being performed.

The second piece had the wonderfully descriptive title: Leonardo Dreams Of His Flying Machine. The opening burst into dissonant flight in a work that embraced the dramatic. The vocal landscape was rich, enhanced by miniature suspended cymbals and tambourines to sex-up the score. The result was a fitting tribute to the great innovator’s visionary ornithopter and his enduring fascination with flight.

As visually engaging as the conductor and chamber choir undoubtedly were, I couldn’t take my eyes off the elephant in the room: an upright piano, front and right of stage. Then, halfway through the programme, Mr Whitacre graciously welcomed the festival’s artistic director and distinguished pianist Christopher Glynn to the platform.

The composer’s Seal Lullaby is his setting of the Rudyard Kipling poem and reminded me of the music by Howard Blake in Dianne Jackson’s animated film of Raymond Briggs’s , The Snowman. The tonal harmonic clusters and gentle dissonances were very effective and sweetly sung, but it was a bit sugary for my palette. Given the instrument’s limitations, Christopher Glynn’s ability to produce such a refined sound was impressive.

Whitacre’s Sing Gently impressed both as a choral work and in its timely ambition. Written in 2020 during the global Covid-19 lockdown, the piece was commissioned for Virtual Choir 6. Its premiere performance featured 17,572 singers from 129 countries – making it his largest virtual choir to date (I looked these statistics up).

The setting of the lyrics – “May we sing together, always. May our hearts always be gentle” – was simple and unembellished, and the performance sincerely heartfelt. I thought this gentle plea for empathy, community and kindness really resonated in a world that seems to be embracing the exact opposite.

The composer’s Hurt couldn’t be more different. It is actually a choral arrangement of a Trent Reznor song recorded by Nine Inch Nails as part of their iconic 1994 album, The Downward Spiral and later by the great Johnny Cash on 2002’s American IV: The Man Comes Around.

National Youth Choir of Scotland artistic director Christopher Bell

The choir delivered a genuinely rich, darker sound world with prominent dissonances reinforcing the rawness of text: “I hurt myself today/ To see if I still feel/ I focus on the pain/ The only thing that’s real”.

The choir’s role worked brilliantly: transforming from support, commentary and then integrating with the excellent soloist. The sustained minor second cadence created a haunting effect.

The mood shifted again with two of Moses Hogan’s well-known arrangements of African American spirituals: Elijah Rock and Joshua Fit The Battle (Of Jericho). Both pieces were great, bristling with vitality and razor-sharp articulation.

The vocal narrative was driven with authentic intent. However, the sheer rhythmic energy, dramatic dynamic contrasts and interplay between the powerful homophonic sections and lighter, more intricate imitation passages of the latter lingered longest in my mind.

Before looking at the musical offering from Bach, I must give a mention to Christopher Bell, the long-serving artistic director – and driving force – behind the very highly regarded NYCOS chamber choir. A point generously acknowledged by Eric Whitacre.

This and a slight whinge: the concert was about 15-20 minutes too long which, given the seating on offer, was a bit of an ask.

For me, the highlight of the concert was Come, Sweet Death: J S Bach, arranged (or rather, reimagined) by Edwin London and realised by Rhonda Sandberg.

That title needs a little unpacking: Bach’s Komm, Süßer Tod (Come, Sweet Death) was originally written in 1736 for solo voice and basso continuo. Edwin London’s concept transforms it into a richly layered choral work – the true act of creative reinterpretation – freeing the singers from strict rhythmic coordination, a distinctly modern choral approach. But it is Rhonda Sandberg who created the practical performing score, bringing London’s vision to life.

The choir reverted to surrounding the audience, with Eric Whitacre directing from the centre. All seemed like business as usual, as the Bach arrangement exchanged lines of recognisable authenticity. Then, suddenly, that world stopped – as if someone had pressed a button – and we were transported into the most exquisite, psychedelic, timeless sound world.

The music floated, as the choir bled out the original sacred tune like some otherworldly canon. A work of genius? Quite possibly. And a fitting close to a concert that constantly surprised.

Review by Steve Crowther