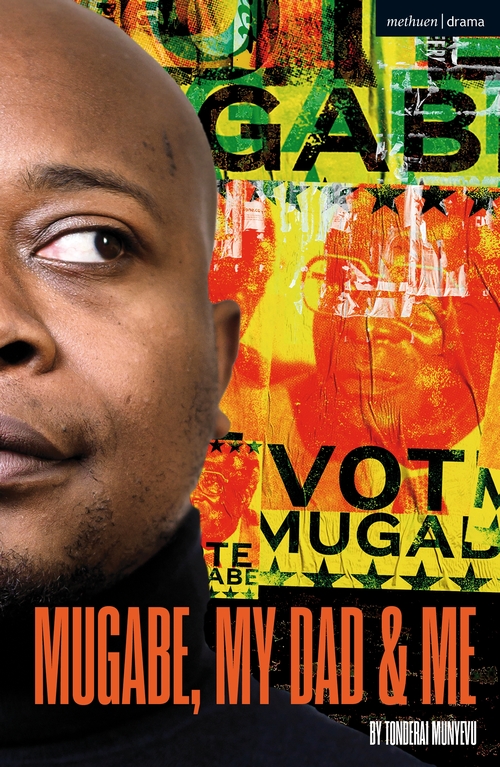

ZIMBAMWEAN writer-performer Tonderai Munyevu’s new one-man show, Mugabe, My Dad & Me, appears in York Theatre Royal’s brochures for both the Summer Of Love and The Haunted Season.

“Which one suits it best, Tonderai?”, he is asked, when shown both. He smiles, then decides: “I think ‘Haunted’. It sounds longer lasting. ‘The Summer Of Love’ sounds impermanent.”

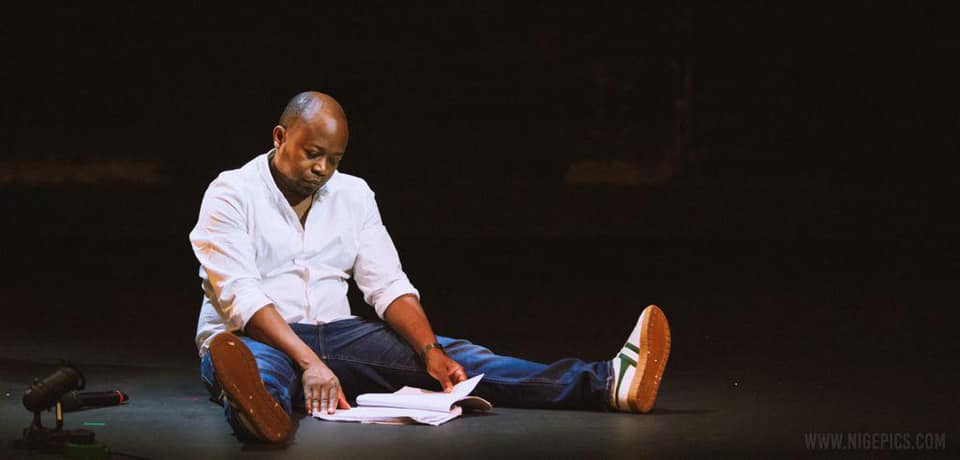

Tonderai is sitting by the first-floor bar at the Theatre Royal, ahead of his long-promised, pandemic-delayed world premiere opening tonight (9/9/2021), directed by Theatre Royal associate artist John R Wilkinson.

“I did a job in Bristol, then one week off, and we were going into rehearsals when everything stopped,” he says. “It’s just been postponed and postponed but I’m glad that John and the Theatre Royal have stuck with it.”

Mugabe, My Dad & Me, running until September 18 in the main house, charts the rise and fall of one of the most controversial politicians of the 20th century through the personal story of Tonderai’s Zimbabwean family and his relationship with his father, against the backdrop of the abiding legacy of British colonisation.

“Around the time when Robert Mugabe was deposed as president in 2017, I just felt like I needed to be back there,” he recalls. “At that point, I hadn’t been there for a few years, not for safety, but more for work and family. I found it was triggering a reaction in me, thinking, ‘I’m going to be in England, and not part of this amazing turnaround’, when I want to experience it’.”

Initially, Tonderai pondered doing a play based solely on freedom fighter-turned despot Mugabe’s speeches from 1962 to 2017, or “potentially to 2018, when he did that final press conference that was so telling”. “But then I thought, when I looked at my father’s story, being born in subjugated Rhodesia, I should tell that story too,” he says.

“I just knew my father’s basic story; I knew he was my dad; he drank too much; he womanised; he was fantastic, such fun, but he was a wife beater too. He lost his job as an accountant – I was about 11; he was in his 40s – and life just changed for him at that point.

“Just as Mugabe’s speeches changed from calling for equality and England knighting him to the speeches of the 1990s and his fall-out with [international development secretary] Clare Short and ‘Prime Minister] Tony Blair, going against the Lancaster Agreement, over how land was to be dealt with and how people would be compensated. That fall-out led to an impoverishment of Zimbabwe that was unparalleled.”

Based in London, Tonderai set to writing Mugabe, My Dad And Me. “I knew if I made it too political, we’d lose the sense of a story being told, but if we could see it through a family’s eyes, with the story of my father dying in an impoverished state, after I left for England with my mother when I was 12, that would work better,” he says.

“The story of Zimbabwe is the story of Mugabe and the story of my father’s generation, but also the story of my generation, who have moved away from home and are grappling with who they are, when you’re asked, ‘Where do you belong?’, and you know you are technically part of that culture but you’re not there anymore, so where do you belong?”

A quarter of Zimbabweans left southern Africa in the big exodus around 2003. “That happened once the economy tanked, the white farmers left and the land was not being cultivated. It started a very tragic downward turn,” says Tonderai.

What about his father losing his job? How come? “The issue involved my father and another accountant at work having a dispute. They said my father wouldn’t be fired if he offered an apology, but he felt hard done by and so he didn’t apologise.” Instead, he left the company.

“My mother and I then left [for London] before it got really bad for him, and I would keep in touch with letters, but not really knowing how things were for him. But then, when I went back, I learnt what really happened, with my uncle being killed when he was only 17 by white Rhodesians who had paraded his body as a warning to those who were guerrilla-fighting in the fields for freedom,” says Tonderai.

“My family was never offered the land that was promised to freedom fights, so Mugabe didn’t deliver on that promise. There’s no-one with moral authority in this story as you can’t defend Mugabe, but equally Blair had a superficiality about him.”

Learning more of his father and his family’s back story led Tonderai to feel more sympathetic towards him. “Though my mother says, ‘No, whatever happens in your life, it doesn’t justify you being a wife-beating, womanising drinker’.”

As for Tonderai’s own sense of identity as an African, Catholic, gay artist, he says: “It had always been connected with Mugabe’s long, long life, like his contemporaries, The Queen and Prince Philip. Now I had to grapple with the President no longer being on pictures everywhere, but also that joy that now we have a democracy, we can protest on the street.

“I started looking at things, about where I wanted to be, and I wanted to understand myself, and part of that was understanding my father. If you’re an artist, you’re an emotionally and intellectually mature person, and I want to investigate that.”

Nothing is simple in his assessment. “The colonisers were ostensibly a negative force in that land, but in some ways positive too, just as Mugabe was an icon of liberation but then tainted by his later actions, and my father was an amazing man, but he was violent too,” says Tonderai.

“In Africa, we have been colonised, but we have colonised ourselves too…some people think Zimbabwe is worse now [post-Mugabe]. I think it’s a very journey to having the opportunity for young people to have the choice of what happens in that country because Zimbabwe is still locked into that thing of ‘What war did you fight in? Why do you, as a young person, have the right to say what Zimbabwe should be?’.

“It does feel like we have to wait for a while to see what the future path will be for Zimbabwe. We have a military hold on religion. You feel despondency because you have hope, just like in South Africa, with Nelson Mandela’s presidency, so when we start looking at African culture, maybe it will be more attuned to Marxism, Socialism for sure, but not democracy as it stands now.

“What I have to do humbly in this story is to show how complex it is and to say there are no easy solutions.”

Tonderai ponders: “Is it more helpful to say that humans have always done it – subjugating people – but we don’t have to define ourselves now by the same standards, when we solve our problems by focusing on our resources, on education, to be fully human, without racism.

“Rather than having to be respected by a white person, or a white person having to admit that they did wrong, instead our priority is our children and our sense of worth that is not defined by subjugation or being considered lesser by another race.

“We move forward. The broader thing that has humbled me in doing Mugabe, My Dad & Me is I could write something where everything feels it’s about race, but instead in this play I’m writing about my culture, the complexities of that legacy and now not defining myself as a migrant in Britain. No-one is ever just a ‘migrant’.”

Tonderai, who last took to the Theatre Royal stage in Eclipse Theatre’s touring production of Testament’s Black Men Walking in September 2019, turns to discussing the “Me” in Mugabe, My Dad & Me. “There’s a point in this play when I say ‘I’m a gay man, I’ve just got engaged and I’m getting married next year’, and though there’s a necessity to say it, I’m a free man and I’m incredibly privileged to be supported,” he says.

“I think my father always liked me because I was confident, erudite, intelligent, fun, and for my father in Zimbabwe in the 1980s, he loved that about me, and I loved that about him. My parents were both bright people and I loved that about them.

“My father said, in the last conversation we ever had, ‘I know I don’t have to ask you if you have a wife’. My feeling is, I think he knew I was gay, rather than him saying I was too young to marry!”

Writing Mugabe, My Dad & Me has proved cathartic for Tonderai. “Yes, things have been resolved by writing it. I think I know who I am now because of writing it; I’m definitely a writer because, until I wrote this play, there were things that I’d never written about; things that were holding me hostage,” he says.

“I never had a straight answer about Zimbabwe, but to have the confidence to be able to talk to a white farmer, Ben, about his life there was important to me. He knew everything by the book and had a very clear argument as to what he thought.

“When I was doing my preparation for this play, I would say, ‘hey, I’m writing this play and I’d like a white man’s perspective on Zimbabwe’, and to have a conversation with such clarity about being Zimbabwean was fantastic. We’re friends now.

“Ironically, he stayed in Zimbabwe, unlike me, and his rhythms of life are dovetailed with the rhythms of nature.”

The pandemic lockdowns have held back the premiere of Mugabe, My Dad & Me, but that has worked to Tonderai’s advantage. “Originally, it was going to be in the Studio, but I’ve always wanted to be on the main stage with a piece like this because I believe it can hold the main stage and I can hold the main stage, and I’m really excited to be performing it on that stage,” he says.

Summing up his one-man show about three men, Tonderai says: “This play is not a raking-up of the past; it’s a play about the present. One of the things that the pandemic has made us realise is that a leader can **** up a country, and sometimes in Europe, we don’t realise how dangerous it is to put people in this position, taking you in a dangerous direction.”

Cue Mugabe, My Dad And Me, premiering from tonight in English Touring Theatre and York Theatre Royal’s co-production in York. For tickets: 01904 623568 or online at yorktheatreroyal.co.uk.

Copyright of The Press, York