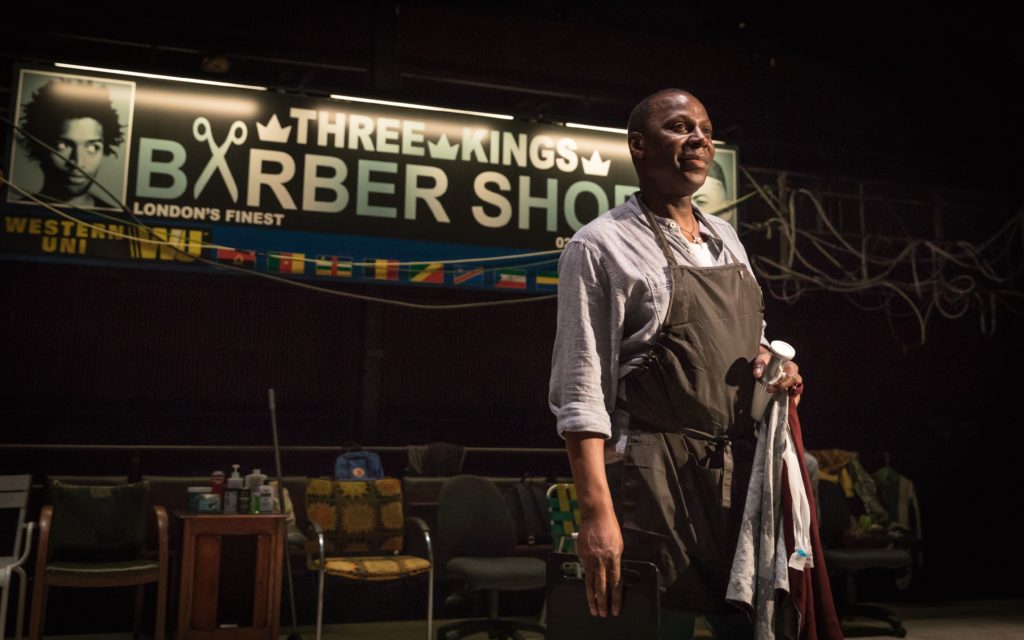

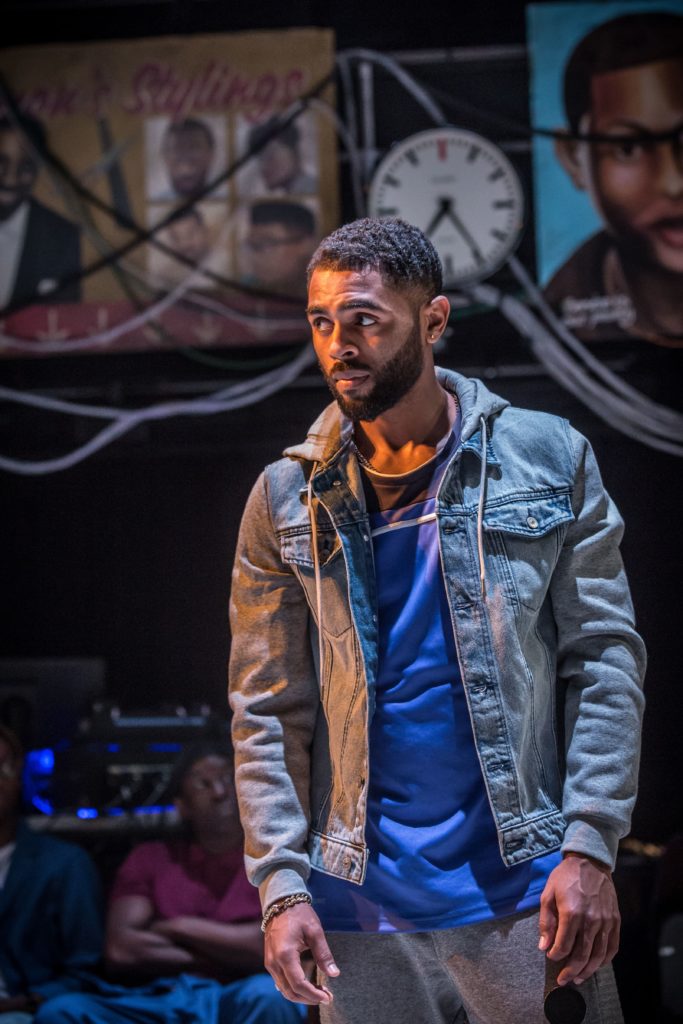

BARBER Shop Chronicles, the Leeds Playhouse co-production with the National Theatre, will be streamed on the National Theatre at Home’s YouTube channel from May 14.

Staged in the Courtyard at the Leeds theatre in July 2017 and filmed at the National Theatre’s Dorfman theatre in January 2018, Inua Ellams’ international hit play will be shown in a never-before-seen archive recording.

Barber Shop Chronicles tells the interwoven tales of black men from across the globe who, for generations, have gathered in barber shops, where the banter can be barbed and the truth is always cutting.

Co-produced with third partner Fuel, Bijan Sheibani’s production went on to play BAM in New York before a London return to the Roundhouse last summer and further performances at Leeds Playhouse last autumn.

The National Theatre at Home initiative takes NT Live into people’s homes during the Coronavirus shutdown of theatres and cinemas with free screenings, each production being shown on demand for seven days after the first 7pm show on Thursdays.

National Theatre at Home is free of charge but should viewers wish to make a donation, money donated via YouTube will be shared with the co-producing theatre organisations of each stream, including Leeds Playhouse, to help support the Playhouse through this period of closure and uncertainty.

For more information, go to https://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/at-home.

Here Nigerian playwright and performance poet Inua Ellams answers questions put to him before Barber Shop Chronicles’ return to Leeds Playhouse last November.

What inspired you to write Barber Shop Chronicles?

“Back in 2010, someone gave me a flyer about a pilot project to teach barbers the very basics of counselling. I was surprised that conversations in barber shops were so intimate, that someone thought that barbers should be trained in counselling, and also that they wanted the counselling project sessions to happen in the barber shop.

“This meant that, on some level, the person who was organising this thought there was something sacred about barber shops.

“Initially, I wanted to create a sort of poetry and graphic art project where I would create illustrations or portraits of the men while they got their hair cut; writing poems based on the conversations I’d overhear.

“I failed to get that project off the ground but the idea just stayed with me for a couple of years, until I got talking to Kate McGrath from Fuel who liked the idea. Together we approached the National Theatre.”

You describe your plays as “failed poems”. Why was this idea better suited to a play?

“The voices in my head just began to grow bigger and louder. When this happens, the poems become multi-voiced and turn into dialogue. Eventually this dialogue breaks away from the poetic form altogether.

“The idea of Barber Shop Chronicles was suited to a play because there were several voices feeding into the conversations within the sacred spaces that barber shops seemed to be.

How did you create the show?

“I began with a month-long residency at the National Theatre in London, then a week-long residency at Leeds Playhouse. I then had six weeks of research travelling through the African continent; in South Africa, Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria and Ghana.

“I returned with about 60 hours of recordings, which I whittled down to a four-hour play and then, eventually, to an hour and forty-five minute show.”

How does it differ to write for other people to perform rather than yourself?

“It’s not that different. I guess I just know from the get-go that I’m not going to be the performer of the text. The difference is when it comes to the rehearsal period. Up until then, when I’m writing, it’s just various shades of my voice speaking in my head, or various shades of me coming out in various voices in my head.

“Then, when I get into the rehearsal space and I see other actors take on the lines, it becomes something else. Initially there is just a story that I’m trying to find the best voices to articulate.

“Also, whenever I write poetry, I don’t always imagine I’m the one performing it because most people will first interrogate the poems in book form. They will read it with their own voices.”

How does it feel to write the play and hand it over to others to bring to life?

“It’s all about trust and that is mediated by the director. It can be very nerve-racking. It can also be very exposing for other people to take your words and do what they will with them.

“They can find that moments in the play are not as subtle as you imagined they were and critique and ask questions. But this is all conducive to creating better art. So, this has definitely been a positive experience with this play.”

Why is Barber Shop Chronicles so important today, and what do you hope people will take away from the play?

“In the past few years, images of black bodies being brutalised by law enforcement were everywhere. On Twitter. Shared in WhatsApp groups. On prime-time news. As a prequel to think pieces, from the New York Times to the Guardian. The images and stories were trending in the US and in the UK.

“I can’t speak about the importance of my work; that is an equation solved by an audience, but I can speak about the psychological violence those videos and images did, and the need for them to be countered somehow.

“Barber Shop Chronicles does that. It shows black men at rest. At play. Talking. Laughing. Joking. Not being statistics, targets, tragedies, spectres or spooks; just humans, breathing in a room.”

The show has toured to Australia and New Zealand as well as having two sold-out runs at the National Theatre and playing Leeds Playhouse in 2017 and 2019. Did you envisage such success?

“No. Writing is an act of faith, a prayer. You sit before a sheet of paper or a laptop and pour into it your fears and wishes, conversations you have been having with yourself. At some point, you pass that on to the director and the actors and they have conversations with the script.

“You can feed into that and tweak things, but from that point on, it is largely out of your control. It is not a play until the audience have been invited into the room, until the lights go on.

“And every instance of the journey feels like a kamikaze mission or an impossible equation to hold in the mind, let alone arrive at some sort of suspicion of an answer. I could not have envisaged any of its success.”

What was the first play to make you want to write plays?

“It was a play called Something Dark written and performed by Lemn Sissay, who is also a poet, playwright and performer.”

What was your background to becoming a playwright?

“I began writing long poems, which I would perform myself with a little bit of theatrical language. I slowly began to write longer poems to be performed by other people, then for larger casts and from there I slid into writing radio plays and subsequently stage plays. Now I’m exploring screenplays.”

What was the hardest play for you to write?

“I think this one, the Barber Shop Chronicles. It’s been seven years in the making, 13 drafts. I had to travel to six different countries on the African continent and spend a lot of time in barber shops in London and in Leeds. I covered thousands and thousands of miles in order to write the play.”

Which playwrights have influenced you the most?

“I’m influenced mostly by poets, if I’m honest, more so than playwrights. William Shakespeare, Evan Boland, Elizabeth Bishop, Saul Williams, Major Jackson and Terence Hayes are my touchstones.”

What is your favourite line or scene from any play?

“I think it’s from Hamlet, the line,‘the substance of ambition is the shadow of a dream’. Guildenstern says that in Hamlet; powerful, beautiful, delicate and barely there. Once you pry into that sentence, you realise how fragile it is.”

What’s been the biggest surprise to you since you have had your writing performed by actors?

“Seeing how much better they are at performing and delivering text than I am! Obviously, they’re actors, it’s their job. But as a poet and a performer of one-man shows, I thought I had a good and natural knack for things, but seeing the range, dynamism and depth they can bring to a single line, the humour, the intention, the discipline, the precision, the knowing; that has been incredible.”

What has been your biggest setback as a writer?

“Time. More than anything else. I do a lot of different stuff, a lot of exciting stuff, and I’m excited by a lot of different kind of things and I want to do everything. Having only one of me is the problem, I wish I had a doppelganger.

“Money also plays a factor, but I’m a typical Nigerian: I make something out of nothing, and always figure out how to make things work.”

What is the hardest lesson you have had to learn?

“Something a lot of writers have to learn, which is to kill your babies. What works for you might not work for an audience or for someone else. You have to learn to be porous, to let go of things.”

What would be your best piece of advice for writers who are starting out?

“Be yourself. Chase your own weird, multi-coloured, insecure, deranged, marginalised rabbits down the rabbit hole of your imagination and see what coughs up. See what you find. Enjoy what rabbit holes, what warrens, what mazes your own imagination and your idiosyncrasies lead you down and write yourself out of it.

“Your own world view, how your flesh and bones and blood enclose the machine of your mind, how it filters the world through your particular sense. These are the most precious things to you as a writer; you have to guard those things with your life because the longevity of your creative life relies on it. Be yourself, in a nutshell, that’s it.”

Did you know?

INUA Ellams was the guest headliner at Say Owt Slam #22, York’s combative spoken-word forum, at The Basement, City Screen, in May 2019.