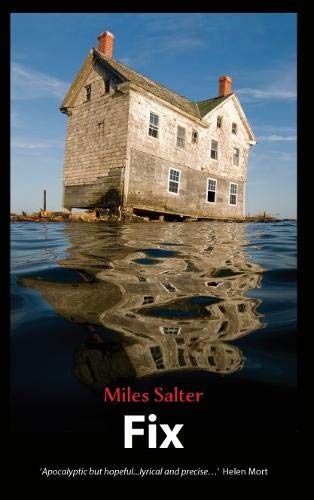

YORK poet, storyteller, journalist, songwriter and radio presenter Miles Salter has come up with his Fix for a seven-year hiatus.

He has released a poetry book of that name on his own new imprint, Winter & May – “it’s a way of saying ‘for all seasons’, reasons Miles – after a burst of writing in the pandemic ended the lull since his second collection, Animals.

In his apocalyptic, sometimes discomfiting yet hopeful miniature narratives and prose poems, Miles’s observational writing spans climate change; the rise and fall-out of love; loneliness and grief; rock’n’roll; the rites of passage through childhood, adolescence and beyond, and life’s flow being put on hold in pandemic lockdown, his tone ranging from deeply dark to darkly witty, quizzical to surrealist.

CharlesHutchPress fixes it for Miles to answer Charles Hutchinson’s frank questions on Fix and more besides.

Why the seven-year hiatus between volumes two and three: had it become a seven-year glitch or itch over that time, Miles?

“I’m a bit of a tortoise. I find that, generally, it takes a while for a project to come to fruition. I can be a real perfectionist. I always think I can do better.

“But the long gap wasn’t intentional. I went through a seismic mid-life crisis. That really slowed everything down. My life was a mess for a while. Some of the poems came out of that. I had a couple of years where I didn’t do much at all, no writing or anything. Just tried to look after myself and keep going. It was very grim.”

At the epicentre of that crisis was the end of your marriage in 2016…

“It took a long time to recover. I was devastated, and suicidal for a while. One of the poems that wasn’t included in the book was about looking for ways to end my life. There was a period in 2017 when I wanted to die. A friend of mine said, ‘You cannot do this to the kids’, and they were absolutely right.

“One poem, Said, details exchanges between me and my ex-wife at the time of our separation. It was a very difficult time; I wanted to save the marriage but it wasn’t possible. That poem reflects what happened. Let’s say I was trying to capture two different voices.”

Given your frankness about your marriage coming to an end, and your subsequent suicidal thoughts, is there anything too personal for poetic expression?

“Fix is very confessional. It’s a risk to write about personal things. Some people have read the book and found it a little uncomfortable, because of the subject matter, although they also said it was moving.

“I feel that vulnerability is important in all art. Otherwise, how are you going to touch people? Overall, I think the balance is about right. Those poems are a record of something traumatic. There are funny poems in the book too!

“I talked about it with Carole Bromley, who’s a friend and mentor, and I reeled off a list of confessional poetry books like Stag’s Leap (about the end of Sharon Olds’ marriage), and Carole said, ‘Well, you’ve just listed my favourite poetry book’. That was very heartening.”

How have you changed as a poet over the past seven years?

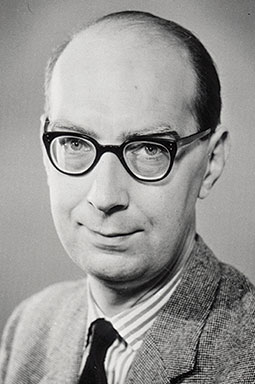

“I think I’m becoming more careful in the writing, perhaps a bit more lyrical and subtle. I like to think that is a sign of maturity. I always liked muscular writers like Philip Larkin, Carol Ann Duffy and Simon Armitage. They all were ‘zero bullshit’ in their writing. But you can have impact without raising your voice too loudly. I think I’m getting better at that.”

How have you changed as a person in that time?

“Good question. There’s a very long answer to that, but a succinct response would be: more mature, a little older, a little less naive about the world. I know myself better. A bit more determined to not mess about, and keener to be more successful than before. Life is short. I want to make the next few years count.”

How do you define what constitutes a poem: once it was rhyme and rhythm; is it now line breaks and a sense of timing for the content’s maximum impact?

“There are a lot of definitions of poetry; I’m not sure I have a definitive one. For me, it would be ‘tell a story with heart and precision, as fast as you can’. But that reflects my tendency to write stories in my poems. A lot of the poems in Fix are miniature narratives and prose poems.”

Does being a songwriter have an impact on your writing of poetry? How do poems differ from lyrics?

“I do find them to be very different things. My songs are more sloppy and more impressionistic. The poems are more crafted. Paul Simon sang once about ‘words that tear and strain to rhyme’, and he was spot on.

“With songs, you’re trying to match ‘rain’ with ‘pain’ or ‘again’. My poems dispense with that, most of the time, so the poems are much more liberated. I’d like to get closer to Del Amitri’s Justin Currie and Leonard Cohen in their song-writing, closing the the gap between poems and songs.”

Why did you choose “Fix” for the title? The word has multiple meanings: to mend a problem; to fasten; to “fix” a sports result; to be “in a fix”; to decide or settle on a date; to fix your eyes on someone; a drug “fix”. Which “Fix” is it for you?

“The big theme of the book is living in an imperfect world. The title was an allusion to addiction, to being in a fix, to trying to make things better. I liked the ambiguity. [Fellow York poet] Antony Dunn had a book called Bugs, which has three meanings. Maybe that was in the back of my mind.”

If you could fix one problem to improve the world, what would it be?

“Climate change. We’re all in big trouble. I have two children and I am scared for them. It’s very frightening. I keep writing about it, as if warding off a bad dream that keeps coming back.”

Dark humour has its place, but what else drives you in your writing. Is it cathartic?

“The humour is important, because life is funny and ridiculous as well as difficult and sad. Thomas Merton once said, ‘I want to write a book that contains everything’. I know what he means.

“There’s a Justin Currie song called At Home Inside Me, which has a similar feeling. As an artist, you want to encompass everything. There’s something universal about art. It’s funny, beguiling, unsettling, inspiring…”

Does something make more sense to you by the end of a poem than at the beginning?

“The best poems, usually, are the ones where you don’t know where you are going. You just follow an idea, and it takes you down a little rabbit warren. It’s a very exploratory thing. Was it Picasso who said ‘If you knew what you were doing at the start, what would be the point?’ Can’t remember. Somebody like that!”

When do you know a poem is finished? Artists often find it difficult to decide when a work is complete. What about you?

“Fix was exhausting at the end. Multiple revisions and then more, and more. It went through 16 drafts. I’m a bit of perfectionist. I just want stuff to be really, really good. Some of the poems I thought were finished, but I showed them to writer friends and would always try to revise them in light of what people said. I’ve learnt that a dodgy phrase is ‘That will do’. Revision is important. Do it again!”

Writers are outsiders, whose observations make us look differently at the world around us. Discuss…

“Yes, absolutely. Writers are outsiders, and sometimes they are difficult, prickly people. But we need their perspective, the way they hold a mirror up to the world. What would literature be without George Orwell, Margaret Atwood, Philip Larkin, D H Lawrence, Ernest Hemingway? We need outsiders sometimes. They show us how life is, and how it could be different.”

You name your influences as Larkin, Duffy, Armitage. Why that trio?

“They didn’t pull any punches; they talked about life in such an uncompromising way, and they were all brilliant with language. Larkin’s The Whitsun Weddings is one of the greatest poems of the last hundred years, I think. It’s so moving.

“He has a bad reputation as a human but the writing is wonderful. I used to stand outside his house in Pearson Park in Hull and go ‘that’s where he was’.

“I always admired Larkin for the way he was so honest about the more unpleasant aspects of life – he wrote beautifully but was never sentimental. Like him, I try to balance the dark elements with some humour, too. I didn’t want Fix to be unremittingly bleak. I really wanted it to feel life-affirming.”

…and Duffy and Armitage?

“I worked with Carol and Simon when I ran the York Literature Festival. I put Carol on three times. That was a buzz.

“Armitage’s Seeing Stars was a big influence on me; it’s an amazing book. He walks a tightrope between humour and horror. Beyond Huddersfield – a bear in a recycling plant. It starts light and funny and gets really dark. Brilliant.”

Your candour within Fix takes in expressing frustration with men being portrayed in a negative light in the poem Shed. Over to you, Miles…

“In the wake of Me Too, there’s been a lot of anger about male behaviour. Some of that is entirely justified – abuse is unacceptable. However, I also see lots of comments that demonise men, and some of that takes place in the poetry world.

“Shed is about toxic masculinity, but there’s a redemptive aspect to it: men can be better, we can move on. I’d like to see that reflected in the discourse, instead of ‘aren’t men awful?’ I feel very strongly about it.

“The highest risk category of suicide in the UK is men aged 45 or under, and I was nearly one of those statistics. Voices that demonise men are not helping, frankly. There’s a lot of shame – and shaming – going on out there, and we need to find a more rounded way of talking about things.”

Your poems stretch from realism to surrealism. What draws you to fantasy: a need to escape; a wish for change?

“I like that space where you take a real situation and twist it a little, so it becomes more surreal. I like to have one foot in the real world and one in a place that is much less familiar.

“I always had a slight feeling of guilt about fantasy and escapism, until I saw [artist] Grayson Perry talk about escapism, and how it’s OK and important. That really helped me a lot. I think imagination is hugely important. We need, as a culture and society, to be more imaginative. I hate the way technology is making us less imaginative, I find it really depressing.”

Is that why you have given your book imprint Winter & May the tagline “Books for Humans”?

“In an age of technological dependence, the motto stands as an attempt to reach for human creativity and independence. It scares me how we’ve all been sucked into thinking like machines.

“Part of me longs for a Utopia where we’re much closer to the earth, and much less attached to technology. One of the apocalyptic poems in the book, Witness Statement, foresees a society where machines take over from humanity.”

Despite the stultifying frustrations and uncertainties of the pandemic cycle of Government-enforced lockdowns, how have you been keeping artistically busy, aside from publishing Fix?

“My band, Miles And The Chain Gang, released a couple of videos in 2020, When It Comes To You and Drag Me To The Light, and we’re working towards making an album.

“We’ve been going two years, and it’s been a slow burn. That’s partly because of Covid, but the songs are really strong and the band are brilliant. I’m optimistic about what we can do in the future.”

How is your regular Wednesday night slot on Jorvik Radio, hosting The Arts Show, going?

“I’ve interviewed luminaries such as cookery book writer Nigel Slater, young adult author Melvin Burgess and Barnsley bard Ian McMillan.

“Talking to Ian was great. He’s one of those writers who really inspired me; he’s so good at wearing different hats, but it’s always about communication and connecting with people. That’s where I feel happiest. Communicating makes me feel more alive.”

How do people respond when you say you are a poet?

“Ha! I don’t really say that. I say I’m a communicator.”

Musician, poet, broadcaster, communicator: why is communication so important to you?

“I just feel happy when I’m using words or music to make a connection with people, tell a story, create an atmosphere, impart information. It makes me happy. I’m getting better at it. It’s taken a while, but I’m improving.”

Should you be wondering…

Why has Miles Salter called his publishing imprint Winter & May?

“It was a joke. It was a way of saying ‘for all seasons’. It’s a made-up name, I just liked the way it sounded. Weidenfeld and Nicholson. Winter and May.”

Is this new venture mere vanity publishing for you? “I really hope not. I always had an inkling that I might go into publishing, in some way. I’ve always adored books. The feel of them, the smell, the potential held inside pages. I’ve got ideas for possible projects with other writers, so I hope it’s not just a bit of ego.”

Miles Salter’s Fix is available via Ohm Books at info@ohmbooks.com, priced at £8.95.