The Academy of St Olave’s Winter Concert, York St John University Creative Centre Theatre, York, 21/1/2023

THIS concert in support of the Jessie’s Fund charity celebrated the music of Schubert, Beethoven and Schumann.

The opening of Schubert’s Incidental music for Rosamunde did seem a tad tentative, hardly surprising given the occasion and new venue with its somewhat dry acoustic. But the Academy quickly hit their stride with a confident Overture brimming with energy and lovely woodwind contributions, dancing gracefully in their many pastoral guises.

This is the first time I have heard this pick’n’mix of musical treats, and the performance was a delight: warm and dignified (Ballet music in B minor), humming nobility (Entr’acte in D major), decisive tempo shifts and a lovely delivery of that melody (Entr’acte in Bb) and so forth.

Then we were suddenly transported to the musical grown-ups’ table with a thrilling performance of Beethoven’s “heroic” Overture Leonore No. 3. This is a truly remarkable work, symphonic in scope and depth.

The musical journey from dark to light, despair to hope was compellingly conveyed in this focused, driven performance. The ‘distant’ trumpet call (signalling the liberation of Florestan and Leonore) was very telling.

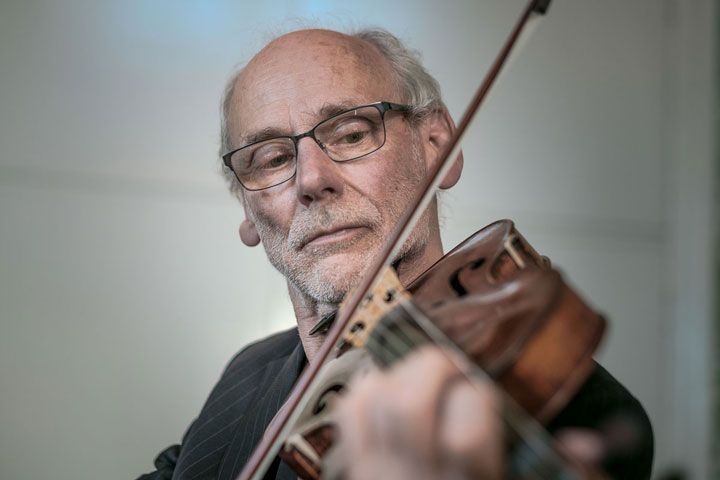

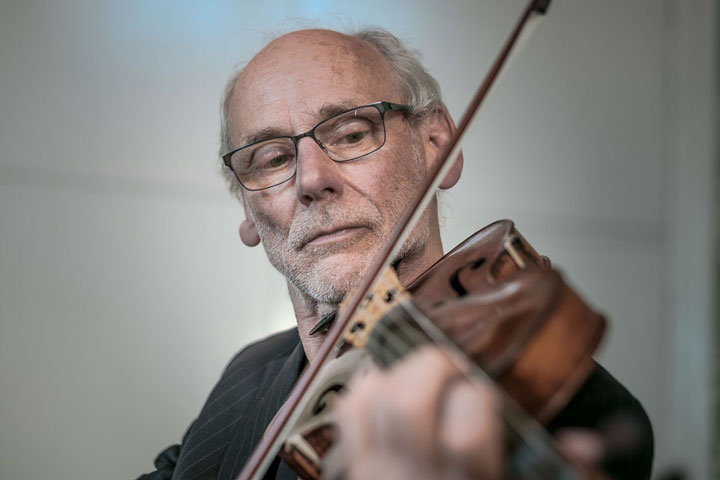

Following the interval was a chocolatey-rich delivery of Schumann’s wonderful Symphony No. 3 (Rhenish). I love this work, indeed I love the musical generosity of thiswork. And so did the orchestra. Under the assured musical direction of conductor Alan George, the performance oozed clarity and confidence.

The Rhenish has no introductory welcome, the starting trigger is fired with the players delivering a high-energy, joyful first movement. There was much to admire here, but balance is the key for the necessary clarity, and this performance had it. I particularly enjoyed the quite extraordinary sound world of the fourth “Cathedral Scene” movement, with gorgeous, ecclesiastical (perhaps?) trombone playing.

But I will leave the final word to the orchestral leader Claire Jowett. Ms Jowett has performed this vital, always understated, almost unnoticed role for more years than I care to remember (sorry Claire). And yet the importance of leading the strings with such certainty of purpose is integral to the success and confidence of all concerned.

Review by Steve Crowther